The world remembers the legacies of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary, the pioneers who conquered Mount Everest. This year marks the 70th anniversary of their historic achievement. To honour this milestone, both families, in collaboration with the Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative, have revitalised two cultural hubs in the Everest region. These are tributes celebrating the rich tapestry of the history, traditions and the Sherpa culture.

Back in 1953, a Nepali-Indian, and Hillary, a New Zealander, scaled the highest peak of Mount Everest. This triumphant ascent, the first in recorded history, turned a lofty dream into a tangible reality. Synonymous with precision and durability, Rolex watches were a go-to for the explorers as they could endure the harshest conditions and unprecedented altitudes.

The climb wasn’t merely a personal triumph; it marked the genesis of a profound mission. Norgay dedicated his life to empowering the Sherpa community. Since young, Norgay trained and fostered safer climbing practices and ignited a spirit of adventure with the students at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling. His legacy lives on through the Tenzing Norgay Sherpa Foundation that is supported by Rolex.

Similarly, Hillary, through The Himalayan Trust, transformed the Everest region with hospitals, schools, bridges and even the vital Tenzing-Hillary airport in Lukla bear his signature. His foundation pioneered environmental conservation by sowing seeds of reforestation around Everest’s foothills.

The Perpetual Planet Initiative, launched by Rolex in 2019, amplifies this commitment. From safeguarding oceans with Mission Blue to understanding climate change with the National Geographic Society, Rolex has partnered with visionaries shaping our environmental future. Today, the initiative boasts over 20 partners, from conservation photographers like Cristina Mittermeier to organisations like the Coral Gardeners. Rolex also nurtures future explorers, scientists and conservationists through scholarships and grants.

As we celebrate the indomitable spirit of Everest’s pioneers, Rolex honours a legacy intertwined with courage, innovation and a fervent love for our planet. Rolex’s unwavering commitment ensures that these stories of triumph, not just on the world’s highest peaks but in the realm of conservation, continue to inspire generations to come.

The perennial watch event returns to Geneva. Here, we'll highlight the biggest watch announcements of the year. So, to kick things off, we begin with the brand that's always on everybody's lips (and wrists): Rolex. More specifically, the Rolex GMT-Master II in Oystersteel in a different colourway.

Rolex returns with a fresh new paint of some of its most iconic models. Like, the GMT-Master II in Oystersteel. If you were expecting the "Coke" version (red and black bezel), you'd be disappointed. But then you'll be elated because the GMT-Master II now arrives in a Cerachrom bezel insert (first introduced last year), either in grey and black ceramic. This colour contrast brings to mind the changing of day and night. Not a bad thing to ruminate, if you're staring at the face of time. There are moulded, recessed graduations and PVD-coated numerals on the insert that makes it easy to read.

The Oystersteel alloy is nothing to sneeze at. This material is highly resistant to corrosion and shocks and even with the onslaught of time, it'll still offers that same lustre as when you first bought it. Opt for either the Oyster bracelet or Jubilee bracelet. Another colour pops out, set against the black lacquer dial, the 24-hour hand displays and the GMT-Master II inscription are in a striking green. According to Rolex, the green is supposed to "highlight our connection to the world.

Similar to other the other timepieces in the line-up, the GMT-Master II has a 40mm case and a Calibre 3285 movement for different timezones.

Recognised for its expertise and the quality of its products, Rolex stays true to the notion of perpetual excellence instilled by its founder, Hans Wilsdorf. This led to a slew of watchmaking innovations. Such as the Perpetual 1908, a masterpiece that’s inspired by the iconic Oyster Perpetual from 1931.

With its legacy ever in the rear-view mirror, the 1908 is a testimony of historic codes with ground-breaking watchmaking innovations. “1908” is the given name of the model. It's an homage to the year Wilsdorf devised the name “Rolex” to sign his creations and registered the brand in Switzerland. It is also a promise of unparalleled performance. Imagine the Oyster Perpetual timepiece but in a slimmer, sleeker design that’s replete with the brand’s signature style.

Crafted in 18k yellow or white gold, the slim case aggrandises a transparent back; a window into its beating heart—the movement finishings within. The innovative calibre 7140 is what powers the watch. A brand-new self-winding movement that is meticulously developed and manufactured by the Swiss Manufacture’s engineers. With two centre hands and a small seconds display, the calibre 7140 is a pinnacle of innovation, backed by five patent applications.

Caged within the sleek watch case is the essence of Rolex’s engineering prowess: the innovation of the oscillator, the Chronergy escapement, the Syloxi hairspring and Paraflex shock absorbers, just to name a few. The 1908 offers a substantial power reserve. Approximately 66 hours of chronometric performance (–2/+2 seconds per day) to keep it ticking without worry of pause.

Distinct Arabic numerals 3, 9 and 12, along with a small seconds subdial at six o’clock beautifully reinterprets the 1931 Oyster Perpetual style. It paints the timepiece in a contemporary allure.

The 1908 is fitted on an alligator strap that comes in either matte brown or matte black. This elegant strap with a green calfskin lining and tone-on-tone stitching, is individually tailored for the new watch. It is equipped with a Dualclasp, a double folding clasp, in 18 ct yellow or white gold. Thanks to its carefully designed shape, the Dualclasp always sits centred on the wrist.

The 1908 is a timepiece, yes. But it is also a milestone, a testament of a brand’s storied mastery and its perpetual quest for excellence.

What makes a watch ‘important’?

There are the big leaguers—chronometers that changed the game for maritime travel; field watches that synchronised soldiers across two World Wars; space age watches that got astronauts safely back to Earth. Then, there are the record breakers—watches that have gone deeper, higher or were more ‘complicated’ than ever before. There are watches that democratised design—step forward the USD3.75 Ingersoll ‘Mickey Mouse’ from 1933; take a bow the first 12 Swatches released exactly five decades later. And there were watches that did the exact opposite—head-spinningly bonkers and eye-wateringly expensive creations like MB&F’s HM4 Thunderbolt and Richard Mille’s RM 011 Felipe Massa.

There are many more categories and many, many, many more watches. Whittling the Most Important down to just 50 sometimes seemed a task akin to studying the history of time itself. Happily, we had the next-best thing to Stephen Hawking to help us. A crack team of industry experts, drawn from all corners of the watch world, from museums to retail, publishing to brand bosses, journalism to actual professors, as our voting panel.

Accept no substitutes. This is the definitive list of the 50 Most Important Watches Ever. (Did we miss any?)

Hyperbole? Perhaps—certainly very few mega-brands owe their success to just one single watch—but there is a strong case to be made. As the 1930s began, Patek, Philippe & Cie was in financial trouble. In 1932, it was acquired by the Stern family, which remains in control today. Seeing the need for a simple, easily marketable watch to put the business on a stable footing (in contrast to the complicated watches that were its stock-in-trade), they introduced the first Calatrava, the reference 96 in the same year, a 31mm design that espoused Bauhaus principles.

Details of its genesis are scant, its designer unknown; the name comes from a symbol used by 12th-century Castilian knights, registered by Patek Philippe 45 years earlier but never used. No one knows why. It’s not even clear why it started with number 96. (Don’t believe stories online that the Calatrava was designed by British antique watch dealer and enthusiast David Penney; he was commissioned in the 1980s to illustrate an authoritative hardback book on the brand’s history, and journalists mistook his signature against drawings of the ref. 96 for the name of the original designer. Penney was born well after 1932 and is alive and well today.)

What is more certain is that ref. 96 was a hit; powered by a respected LeCoultre calibre it provided a blank canvas for all manner of dial designs and iterations, and remained in production for 40 years. It might not leap immediately to mind when you mention the brand name—with the Nautilus on its books, and a formidable history of perpetual calendars, split-second chronographs, worldtimers and minute repeaters, you can hardly blame fans for sometimes overlooking the humble Calatrava—but it is the bedrock upon which so much great watchmaking stands.

In 1933, two companies faced bankruptcy. One was Ingersoll-Waterbury, a watch firm that grew out of a New York Mail business. The other was Disney. A marketeer and former mink-hat salesman named Herman “Kay” Kamen rescued both—despite apparently falling asleep in the pitch meeting. His solution? A watch featuring Mickey Mouse, his yellow-gloved hands rotating to tell the time. Response to the $3.75 timepiece was immediate.

Macy’s sold 11,000 the first day it went on sale, and within two years Ingersoll had added 2,800 staff to cope with demand, and an original Ingersoll Mickey was placed into a time capsule at the 1939 World’s Fair. Today, “character watches” are big news; case in point: Oris’ runaway 2023 hit, a £3,700 watch featuring Kermit the Frog. Meanwhile Mickey (and Minnie) Mouse now grace the Apple Watch and will speak the time when you press the dial. That’s progress for you.

Where the diving watch as we know it began, exactly 70 years ago. The turning bezel for dive-timing, the bare-essentials high-vis dial, the streamlined-but-watertight case: all came about when Blancpain’s scuba-fan boss Jean-Jacques Fiechter teamed up with French war heroes Robert Maloubier and Claude Riffaud, who needed a watch for their new commando unit, to invent the ultimate all-action underwater wristwatch. Rolex had similar ideas—its Submariner followed soon after. But Blancpain’s military-approved cult classic was foundational; rare vintage models are collector grails, and modern versions remain big sellers for the brand.

Sure, it was the first watch to show both the date and the full day of the week, but the Day-Date’s function has always been secondary to its aura. Nicknamed the “President” for having been gifted to (and worn by) Dwight D Eisenhower, it’s the watch that defines Rolex’s association with success, prestige and achievement—something that has remained as constant as the Day-Date’s unmistakable look. It’s not quite true that the Day-Date is exclusively produced in precious metals—an “entry-level” steel version occasionally comes up at auction, although since only five were ever prototyped, not at an entry-level price.

Given both the relentless hype that attaches itself limpet-like to the Royal Oak, and the multiplicity of iterations and styles Audemars Piguet has birthed over the years, it’s easy to forget just what a formidably clever, intuitive and ground-breaking design it was back in 1972.

Tasked with matching the robustness and versatility of a steel sports watch with the crafted beauty that was Audemars Piguet’s stock-in-trade, the designer Gérald Genta came up with the Royal Oak in a single overnight session. It sealed both his and Audemars Piguet’s future legacies, and begat the “sports-luxe” genre in one fell stroke.

Genta’s blueprint was an inspired synthesis of the industrial and the exotic. It was streamlined, housing an ultra-thin automatic movement, and with a look dominated by a screw-laden octagonal bezel, on a case that merged seamlessly into a complex, tapering bracelet. The brutalist dial was subordinate to the gleaming geometries of the case, where contrasting brushed or polished finishes were assiduously hand-applied. The bracelet alone was so complicated that it needed watchmakers rather than case technicians to assemble it.

The Royal Oak did for steel watches what the era’s high-tech architects were then doing for steel buildings—elevating the material of industry and kitchen cutlery to the level of the sublime. “The noble metal of modern-day cathedrals,” was how Genta termed it, according to Bill Prince, author of Royal Oak, from Iconoclast to Icon. At the time, the Royal Oak was the most expensive steel wristwatch ever made, but it unleashed a genre whose impact would only truly be felt in the following decades—and never more so than right now.

With its brash and bold designs, Hublot is the opposite of discreet luxury—something that tends to wind up serious watch collectors. The brand’s “the art of fusion” tagline is embodied in its flagship Big Bang, the first of which layered up ceramic, magnesium, tungsten, Kevlar, rubber and steel into an eye-popping (and prize-winning) new direction for watch design.

Since every Big Bang is technically limited, it also pre-empted today’s drop culture, with future watches incorporating silk, denim, diamonds and sheep’s wool. “People want exclusivity,” its creator Jean-Claude Biver told The Economist. “So you must always keep the customer hungry and frustrated.”

François-Paul Journe produced his first wristwatch in 1991, to a collective shrug from a world not yet ready to embrace artisanal, anachronistic masterpieces from unknown names. Jump ahead eight years and the mood had changed; Journe set up his own brand and took commissions to make 20 tourbillons—selling the watches by “subscription”, ie: half up-front, an idea borrowed from Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Journe’s output throughout the past two decades has been prodigiously inventive, but it took the pandemic to send things into the stratosphere; auction values of the Tourbillon Souverain tripled between 2019 and 2020.

Beloved of die-hard Rolex enthusiasts and casual “one-watch guys” alike, the modern Explorer retains the spirit of the watches that accompanied Tenzing and Hillary (almost) to the top of Everest in 1953 (both climbers in fact wore models by British brand Smiths to the summit itself).

After the ascent, Hillary’s Rolex was returned to the watch company for tests to be conducted on how it had weathered its high-altitude journey, and it is now on display at Zurich’s Beyer Museum. Despite recent flirtations with precious metals, the Explorer remains a paradigm of honest, simple watchmaking that for many really is all the watch you need.

Remember steampunk? In the late-1990s, “Victorian sci-fi” had a cultural moment. It gave us one of the worst films of the decade, Wild Wild West, emo-lads in top hats and, on the plus side, this spectacular timepiece. Inspired by Jules Verne and HG Wells, American creative Jeff Barnes envisioned an impossible watch with multiple porthole dials, rivets and an invisible rotor. Iconoclast watchmaker Vianney Halter made the impossible possible.

Halter and Barnes propelled watch-making into a strange alternative universe. A wormhole opened that subsequent visionaries—MB&F, Urwerk, De Bethune etc—would burst through, reimagining what high-watchmaking could really be.

Through countless iterations down the decades, the “5” shield logo on the Seiko 5 has symbolised the ultimate sturdy, go-anywhere, do-anything all-rounder wristwatch. Affordable, capable and just damn cool, the Seiko 5 has even accrued its own entire subculture around collecting and modding. No collection is complete without one, and for a lot of watch nuts, it’s the place where it all begins

In the age of orbiting space stations, communications satellites and Mars rovers, there is something quaintly old-school about a mechanical watch being used in space. Computers may crash but, the thinking goes, a mechanical watch will continue to work in all conditions: high temperatures, below zero, low gravity and when all tech has shut down, in darkness.

Omega’s Speedmaster line was made with racing-car drivers, not astronauts in mind. It was the first chronograph with a tachymeter scale on the bezel, to measure speed over distance. But the design caught the eye of Nasa astronauts Walter Schirra and Leroy Cooper.

The story goes that the pair then lobbied Nasa operations director Deke Slayton to make the Speedmaster the official watch for use during training, and, ultimately, flying. In 1964 Slayton issued an internal memo stating the need for a “highly durable and accurate chronograph to be used by Gemini and Apollo flight crews”.

Proposals were sent to 10 brands: Benrus, Elgin, Gruen Hamilton, Longines Wittnauer, Lucien Piccard, Mido, Omega and Rolex. Only four answered the call: Rolex, Longines Wittnauer, Hamilton and Omega—with Hamilton disqualifying itself by submitting a pocket watch. The remainder underwent extreme trials: 48 hours at 71°C, four hours at –18°C, 250 hours at 95 per cent humidity, temperature cycling in a vacuum, and so on.

Nasa declared Speedmaster “Flight Qualified for All Manned Space Missions” in March 1965. It went on to become the first watch worn on the Moon—by Buzz Aldrin, in 1969—and to play a crucial role in the Apollo 13’s re-entry to Earth in 1970, when it was used to time a crucial 14-second burn of fuel. (As seen in Tom Hanks’s 1995 film, Apollo 13.)

It would be remiss of any company not to dine out on marketing gold like this, and Omega has certainly done so, issuing endless Moonwatch variants ever since. Happily, its product backs up the hype. “Speedmasters have it all: great chronograph movements, an amazing case design, fantastic dial and hand aesthetics and an unbelievable history,” says vintage-watch expert Eric Wind.

The watch that no one saw coming, that no one could get hold of, and yet absolutely nobody could avoid back in the heady days of… er, 2022. Can it really only be last year that streets around the world were shut down as mobs of thousands rushed to procure a plastic (sorry, “bioceramic”), battery-powered Speedmaster made by Swatch?

MoonSwatch fever may have died down now, but few modern watches have nailed the moment quite so perfectly. Amid a post-pandemic climate of high/low mashups, vibe shifts, blurred cultural lines and hype—so much hype—it nailed the zeitgeist dead-on, becoming the most consequential Swiss watch release since the original Swatch in 1983.

The perpetual calendar—complex, elegant, poetic—is the emblematic watch of haute horlogerie. And, like so much of haute horlogerie, Patek Philippe defined the form. Patek introduced its first perpetual for the wrist in 1925. But in 1941 it did the near unthinkable and put the complication into serial production—twice over.

Reference 1526 was a perpetual calendar with moon phases, but Reference 1518 really blew the doors off, with a chronograph thrown in and a layout of high-complication magnificence. It wasn’t until 1955 that another brand, Audemars Piguet, was able to compete with its own perpetual calendar, while the perpetual calendar chronograph has remained a signature combination for Patek Philippe and its collectors.

Braun’s concept of German modern industrial design, a mix of functionality and technology, is lauded everywhere from MoMA catalogues to Jony Ive interviews. Its design principles have been applied to calculators, coffee grinders and cigarette lighters. But you could argue the wristwatch is its purest distillation, the work of one of the Braun’s designers, Dietrich Lubs, and Dieter Rams.

Taking a lead from 1975’s AB 20 travel clock, its aim was to display time in “the most functional way possible”. That meant white type on a black dial, a yellow second hand that “pops”, and Akzidenz-Grotesk—the font known as “jobbing sans-serif”. As in, it is used for jobs—including New York City’s transportation network. The designer’s designer watch.

Well-heeled travellers of the early 1950s encountered a new phenomenon. They didn’t have a name for it yet—consensus suggests that the phrase “jet lag” wasn’t used until the mid 1960s—but the discombobulating effects of flying across time zones were clear. Passengers could bear the inconvenience, but Pan Am, concerned for its pilots, wanted to find a solution. It was naively thought that a device capable of displaying the body’s “home” time at a glance could help overcome the effects—so legend has it, anyway.

Rolex produced the GMT-Master reference 6542 in 1954, and the rest is history. The rotating bezel had already seen the light of day in the previous year’s Turn-o-graph (proof that not all Rolexes were lasting hits), but the addition of a 24-hour scale and day-night colour scheme nailed the formula. It’s easy to overlook how bold the two-tone design must have been in the postwar years, and the GMT-Master has maintained that outgoing character.

The variation of colours that followed, and the tendency of the early materials to patinate and degrade in interesting ways, have spawned a rich lexicon of nicknames and cemented the reference’s enduring appeal. In modern times, at least prior to 2023’s bonanza of emojis and bubbles, the GMT-Master II was where Rolex went to experiment, developing single-piece ceramic bezels, introducing meteorite dials, gem-set bezels and even subverting its own codes by adding the dressy Jubilee bracelet in 2018.

The introduction of a left-handed model in 2022 only added to the hype. Today it is one of the hardest Rolexes to acquire. Mechanically and aesthetically, Rolex hit upon a template that performed a simple task with clarity, character and composure, and left its imitators behind.

The Cartier Santos-Dumont, launched in 1904, claims not one but two places on the watch history books: the first pilot’s watch and the first wristwatch designed specifically for men. Created to get around the impracticality of flying with a pocket watch, it was born after Brazilian pilot Alberto Santos-Dumont raised the issue with Louis Cartier.

Given Cartier’s red-carpet-reputation today the watch boasts a decidedly non-showy design. Characterised by eight screws, its case seems to have been influenced by a contemporaneous square pocket watch, with curved lugs and a leather strap designed to make it comfortable to wear on the wrist. Meanwhile, the instantly readable dial design foreshadowed the Art Deco movement of the 20s and 30s and remains a look that defines Cartier watch designs to this day.

With headlines declaring “Mr Santos-Dumont’s First Success with a Flying Machine” still fresh in people’s minds, by 1911 Cartier was marketing “the Santos-Dumont watch” in platinum and gold, its daring-do aviation connection piquing the interest of a new demographic: men. The model would be relaunched by Cartier twice after. In 1998, to celebrate the Santos-Dumont’s 90th anniversary, and in 2005 as part of the Collection Privée Cartier Paris.

In 2018 Cartier made it available in steel, the first time the watch had appeared in a non-precious metal, putting it within reach of a new consumer. Its timing was prescient—with interest in men’s watches exploding, there was a newly design-literate customer on the market. Cartier may not use the fanciest movements or the trendiest materials. Instead, it outpaces the competition with 100 years of rock-solid designs, and watches that look unique.

Every year, Morgan Stanley produces a financial report on the Swiss watch industry. Nine of the top 10 brands by revenue date back 100 years or more; the same nine all produce at least 50,000 watches a year.

The outlier is Richard Mille: barely 21 years old and making a shade over 5,000 watches a year, it outranks giants like Longines, Breitling and Vacheron Constantin. The secret sauce is complex, but it owes a lot to the technically innovative watches worn by Mille’s sporting ambassadors—and that all began with Massa, way back in 2007.

On Christmas Day 1969, Seiko gave the world its most important gift: the first quartz-powered wristwatch. A decade in development (during which time the Japanese had shrunk the technology from the size of a filing cabinet to something you could wear), it was the harbinger of seismic, lasting change.

The mass production of cheap quartz watches that followed in the 1970s wrought catastrophic damage on Swiss watchmaking, although the scale of the job losses and closures was down to currency devaluation and the stagnant, uncompetitive structure of the industry as much as the threat of marauding outsiders. Perhaps unfairly, the Astron is forever associated with these effects, rather than as a genuine innovation that made watches more accurate and more affordable.

Almost 35 years after its launch, the F-91W remains not just the world’s most popular digital watch, but the most-purchased watch on the planet. Created by Ryusuke “G-Shock” Moriai as his first design for Casio, it is technically and materially inferior to every other watch the brand produces. That’s not the point. The F-91’s charming resin design, iconic shape, accuracy, perfectly judged number of functions and—last but not least—£15 price make it a must-own. The backlight is absolutely terrible, though.

Technically, you could land a plane using just this watch’s info-packed bezel, but it would be a brave man who’d try. Still, the development of the Navitimer (“navigation” + “timer”) offered something no other watch manufacturer had ever proposed: a chronograph combined with a slide rule, enabling pilots to perform vital calculations like average rate of speed, fuel consumption and converting miles to kilometres. Originally only available to accredited aircraft owners and pilots, the Navitimer was also the watch world’s first automatic chronograph.

“God is in the details” was the dictum of Bauhaus pioneer Mies van der Rohe; the watch designed in 1961 by the Bauhaus-trained architect and artist Max Bill, for the German brand Junghans, doesn’t half bear this out. In its cornerless numerals, its crisp lines and perfect proportions, its minimalism is exquisite and unimprovable; no wonder Junghans has kept this modernist classic unchanged ever since.

One of the most popular modern sports watches, Rolex’s sibling company offers exemplary levels of craftsmanship, quality and value in one impossible-to-resist package. Deftly cherry-picking elements from forgotten 1950s and 1960s Tudors, it kick-started today’s obsession with vintage watches—and sent dozens of rivals scurrying to their archives. Without it, the watch business would look very different.

So sprawling is Omega’s back (and current) catalogue of Seamaster watches, it can be hard to know just what the name stands for. Dive watches? Yes. Sports watches? For sure. But also dress watches? Gosh yes, some true bobby-dazzlers… The answer comes from a 1956 Omega ad: “The Seamaster was designed to share with you the zest of high adventure and the stresses and strains that go with it… There is more ruggedness built into the Seamaster than you are ever likely to call for. It feels good, though, to know you can count on the extra stamina and extra precision which set the Seamaster apart from other watches.”

In other words, however it was styled, the Seamaster represented Omega’s cutting edge: the most water-resistant, robust, precise and easily serviceable watches you could get on the mass market; a next-level product for demanding customers—the ad cited sportsmen, airline pilots, golfers and military personnel as typical wearers.

Launched in 1948, the Seamaster came about as Omega transferred tech it developed in its wartime watchmaking for the British armed forces to the civilian market: screw-back cases sealed with newfangled rubber O-ring gaskets, and high-spec automatic movements that were a benchmark for durability and accuracy. They’re often still in fine working condition today; one reason why early Seamasters have tended to be a gateway watch for nascent vintage-watch collectors—you can still find them for a bit over £1,000, but prices are rising.

When it launched a hardcore dive watch in 1957, naturally Omega made it a Seamaster (the Seamaster 300). In fact, the Speedmaster chronograph was also originally categorized in Omega catalogues as a Seamaster; and so was the ultra-dressy De Ville line. A Seamaster was a watch that could take on anything; and it still is.

In 1955 Rolex took a full-page ad out in the Daily Express (back then, that meant something) to proclaim the wonder of its invention in the 1930s of the self-winding wristwatch. A few months later it inserted an apology into the paper and, in a new ad, corrected what it had previously left out. The convenience of a watch that doesn’t need winding was arguably the fundamental breakthrough in the evolution of the wristwatch; but in the story of its genesis there is, as Master Yoda might say, another.

John Harwood was a watchmaker who, during army service in World War I, became convinced of both the usefulness and shortcomings of wristwatches. He saw the winding/setting crown as a watch’s weakest point, letting in dust and moisture. His solution was radical: a watch with no crown, that could be set via a turning bezel and with a mechanism that wound itself via the motion of its wearer’s wrist.

Harwood took his idea to Switzerland, where he obtained a patent in 1923. He forged a partnership with Fortis to make Harwood automatic watches, recognisable by their knurled bezels and a red dot above the six that told you the movement was running. The winding action was down to a “hammer” mechanism that swung from side to side, tensioning the mainspring.

Launched in 1926, Harwood’s was the first mass-produced self-winding wristwatch, and sold well in Europe, the UK and North America. But the Wall Street Crash of 1929 dealt a hammer blow to Harwood’s business; by September 1931, it was all over.

That year, Rolex patented its own method, the “Perpetual” rotor that swung around freely on top of the movement. It’s the format that proved the basis for the self-winding watches that would become all-dominant; but it wasn’t the first.

The need to tell the time accurately in all 24 time zones is a relatively recent invention in the history of timekeeping. In 1885, the Swiss watchmaker Emmanuel Cottier came up with a world-time system he presented to the Société des Arts. His son Louis-Vincent followed him into the trade, attending Geneva’s horological school and winning several prizes, including a handful from Patek Philippe. By 1931, Louis had perfected his own world-time mechanism.

It was developed for a pocket watch, but Rolex, Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe soon took an interest and he delivered dozens of versions for the latter using his HU calibre, or “heures universelles”. World time-watches made nowadays still follow the Cottier principle. City names circle the periphery of the dial above an inner 24-hour ring that turns counter-clockwise. The ring’s movement simultaneously coordinates the times in all time zones, while the hand indicates the “local” time at the city displayed at 12 o’clock.

Today, Cottier has a square in Geneva named in his honour, and world-time watches provide a time capsule for the eras in which they were made; each dial reflecting the political climate. For example: under German occupation, France switched to central European time—Patek continuing to put London and Paris on the same time zone until the 1970s, making these watches highly collectable.

It’s all about the story with watches, and the El Primero’s is straight from central scriptwriting. It raced to be the first automatic chronograph ever made (it was announced first but was beaten to customers’ wrists by both Heuer and Seiko); the investment nearly broke the business, which went under with orders to destroy the El Primero’s parts and tooling. Defied by one watchmaker, it was resurrected, used to power the Rolex Daytona for a generation, and has finally established itself as a beautiful, technically accomplished watch for people who care about the details.

Water resistance has been fundamental to our conception of reliable wristwatches for decades, but in 1926 it was revolutionary. Hans Wilsdorf, Rolex’s founder, didn’t come up with it himself. But when a patent was filed for a new system to hermetically seal the case via a screw-down winding crown (the most likely area for water ingress), he moved fast, acquiring it and registering the “Oyster” trademark—to symbolise the impregnable seal of the shell—within days.

Next, in 1927, he got swimmer Mercedes Gleitze to carry one as she became the first British woman to swim the Channel and took a full-page ad in the Daily Mail to proclaim its perfect performance during her feat. Thus he announced his breakthrough to the world.

The Rolex Oyster—"the wonder watch that defies the elements" as its advert put it—would change the whole game. It laid the technical foundation for practically every Rolex model since, nearly all of which still carry the name “Oyster”, and drove the wristwatch forward as a sensible, reliable, wearable accoutrement for modern people in a fast-changing, fast-moving world.

Moreover, it inculcated the association of Rolex with robustness, quality and innovation, and confirmed Wilsdorf’s absolute genius for cutting through with inspiring, opportunistic marketing. After that, there was no looking back.

Six decades before the Octo Finissimo or Richard Mille Ferrari UP-01, Piaget created the calibre 9P and calibre 12P, hand-wound and automatic movements of astonishing thinness, produced with none of the high-tech fabrication machinery or design software available today. These established the brand’s reputation for ultra-thin prowess and created an iconic dress watch.

Commissioned by the Ministry of Defence for use by the British Army, this set of 12 watches by the likes of Longines, Omega and IWC, plus long-forgotten names such as Grana, Cyma and Eterna, combined black dials, antimagnetic steel cases and luminous hands to establish an entire genre that lives on today.

Truth be told, most of the 150,000-odd watches that were made only arrived late in 1945; for the preceding six years, British servicemen used something called the ATP (Army Trade Pattern) watch, but it is the Dirty Dozen that has passed into watch-collecting lore. Tracking down a full set remains one of the ultimate grails for collectors the world over.

In 1976, designer Gérald Genta adapted the Royal Oak blueprint to create a Patek Philippe equivalent: shapelier, more sumptuous, more peculiar—not least in its flanking “porthole hinges” that screw shut for watertightness. Made in infuriatingly small numbers, the Nautilus has come to define an entirely modern watchmaking trend: scarcity. It never won’t be a major, major flex; but it’s the sheer exoticism of its form that makes it arguably the most glamorous watch design of all.

Initially known as Le Mans and received so unenthusiastically that Rolex considered discontinuing it, the motorsport-themed chronograph has gone on to achieve the status of World’s Most Desirable Watch. Paul Newman wearing a version (ref: 6239) no doubt helped; his watch later took all of 12 minutes to sell at auction for $17.5m.

A decent return on its original price of USD210. Rolex’s Daytona is one of the greatest chronographs of all time—precious metals, blinged-out dials and Rolex’s strategic limiting of supply have made it an icon. The hard-to-get wristwatch is also a great investment. A stainless steel and ceramic Daytona bought for £12k in 2019 would now sell for twice that.

Often overlooked by vintage devotees in favour of the later 13ZN models with their larger cases and frequent military connections, the 13.33Z, first introduced in 1913, was the very first purpose-built chronograph wristwatch movement. Hand-wound and usually found with enamel dials painted with tachymetric scales, they are beautiful inside and out.

Commissioned by the RAF in 1948, whose airmen would use it for the next 40 years. the Mark 11 put wartime advances in precision, reliability and anti-magnetism inside a design (by the MOD, not IWC) that’s both utilitarian and iconic, becoming the quintessential military aviation watch. Its blueprint has proven endlessly adaptable, yet never better than in its original format.

The Luminor has been called “the essence of Panerai” with a history that is at once serious (until 1993, it was only available to Italy’s military) and silly (its deep-sea luminosity originally came from the use of an unsafe radioactive compound). Its signature crown-protection guard speaks to old-school diving equipment, as well as signalling its “if-you-know-you-know” appeal.

The Seamaster range may include world timers, yachting chronographs and the cult favourite Ploprof. But at its heart is the Seamaster Diver 300M. First produced in 1957, it has never quite achieved the mythos of the Speedmaster—its history more sprawling, its style more frequently updated—but it is still one of the great dive watches.

Comparisons to the Rolex Submariner are inevitable, and the fact that since 1997’s Goldeneye, James Bond has worn a Seamaster brings extra spice to the calculation. In recent years Omega has striven to outflank Rolex on a technical front too, adding antimagnetic and supremely accurate “master chronometer” movements, ceramic bezels, something called a “naiad lock” and sleek black ceramic cases.

For 20 years, MB&F’s Max Büsser has been the wizard at the heart of a movement driving horology in fantastical new directions—think Urwerk’s cyberpunk devices, Greubel Forsey’s tourbillon extravaganzas and, more than anything, MB&F’s phantasmagorical Horological Machines. Inspired by World War II fighter planes, HM4 was Büsser’s biggest risk but arguably his greatest success: a kitsch, postmodern thrill-ride that’s as innovative as it’s outlandish, proving that—in his world at least—anything really is possible.

The question was never, “Can you make a Swiss quartz watch to compete with Citizen and Seiko?” Swatch’s creative director Carlo Giordanetti told this magazine in 2017. But rather, “Is it possible to make a cheap, mass-manufactured product that inspires the personal attachment and ‘soul’ associated with handcrafted equivalents?”

Yes, the first modestly sized range of 12 watches that launched in 1983 were cheap and plastic. But the success of Swatch—or “second watch”—routinely credited with saving Swiss watchmaking from the digital Asian apocalypse, was down to something else: “a new, fascinating way to say who you are and how you feel”.

It took physician and watchmaker Ernst Thomke and his two-man team 12 months to develop the prototype, working backwards by first developing the case, then reducing the number of quartz components and attaching them to it. Plastic wasn’t the only contender, they also looked at wood.

Launched in the same year as the Porsche 911 that shares its name (although the first 911 to officially be described as a Carrera was the 1972 2.7 RS), Jack Heuer’s masterstroke became just as indelibly associated with motor racing. By dint of Heuer’s marketing nous, it soon ended up the preferred watch of the Formula 1 paddock during the sport’s golden era. Jack was a fan of modern design and architecture, and deemed the tracks found on chronograph dials fussy and unnecessary.

After taking a class on watch dials at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology he used the principles of his studies to come up with something cleaner. Between 1963 and 1985 it underwent multiple reinventions, but the original reference 2447 stands as one of the three heroic chronographs of the early 1960s (alongside the Daytona and Speedmaster). An exemplar of mid-century modernism and sporty practicality that is coveted by collectors around the world.

The place: Les Ambassadeurs Club, Mayfair. The year: 1962. Seated at a casino table, two gamblers are going head-to-head. One is a beautiful woman in a red dress; the other, a dashing man in a sharp suit. He asks her name. “Sylvia Trench”. He lights a cigarette and stares at his opponent across the table. “Bond,” he replies. “James Bond”.

Dr. No gave us one of the most famous introductions in cinema and guided us into a new universe of covetable clothes, accessories and gadgets. Though 007 would later defect to Omega, for his debut another brand was tucked beneath his crisp white shirt cuff. He wore a Rolex “Big Crown” Submariner (ref: 6538)—from a new line of diving watches introduced nine years earlier that, as Rolex put it, “unlocked the deep”. (The watch was Sean Connery’s own.)

Ask a child to draw a man’s watch and chances are they’ll come up with something that looks like a Submariner. It is the most recognised, counterfeited and copied watch in the world. Today, thousands of brands produce what may politely be called “Submariner-adjacent” models.

While not the first dive watch, the Submariner was the first to be waterproof to 100m and feature a rotatable bezel for divers to read. The model came into its own in the golden period of sports watches, the 1960s, and as sales rose Rolex began refining and standardising the line.

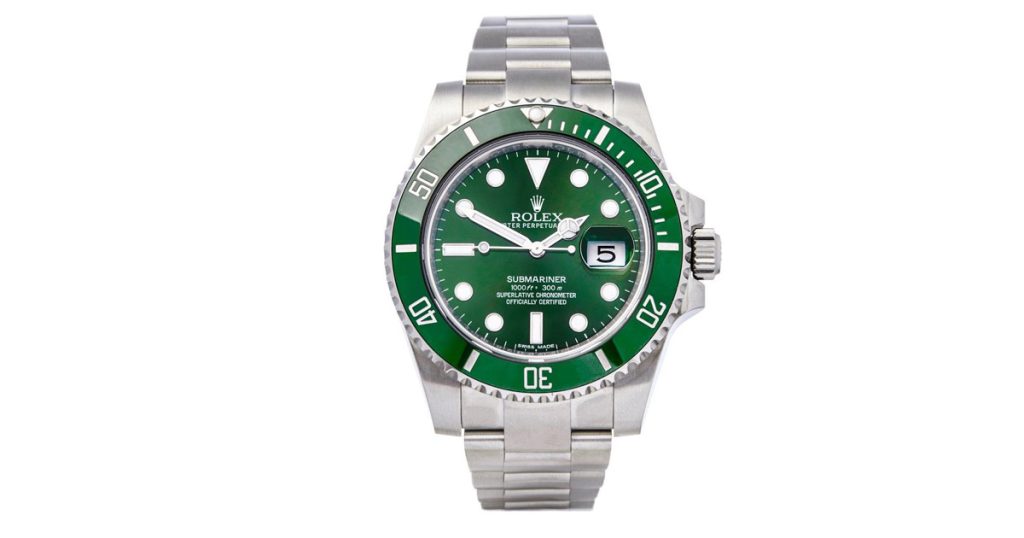

Today’s Subs are waterproof to 300m, with triple-protected waterproof winding crowns, blue “chromalight” luminescent material and ceramic bezels that are unaffected by seawater, chlorine or ultraviolet rays. Meanwhile, the collecting community delights in giving its many references nicknames based on individual design features. They include, but are not limited to, “Hulk”, “Bluesy”, “Smurf”, “Starbucks”, “Bart Simpson”, and, of course, “James Bond”.

The Freak is a significant watch for two reasons. The first is its sheer ambition: doing away with a traditional dial and hands. Mounting the entire gear train and escapement on a bridge that would rotate under its own energy, acting as a colossal minute hand as it did so, was truly maverick. The second is that the idea came from Ulysse Nardin, a 150-year old brand steeped in conservative tradition. The Freak showed the Swiss establishment that it didn’t have to let the young indie hotshots corner the action.

“My feeling is it’s going to be a failure,” the CEO of a well-known Swiss watch brand told this magazine in 2016, with all the foresight of Pete Best. “Apple doesn’t realise that the reasons for buying a watch are very different from buying a phone or Mac. You don’t buy one for the functionality, you buy it for what it says about you, for its design and uniqueness.”

Today, Apple outsells the entire Swiss-watch industry by a wide margin—you only need to look at people’s wrists on the next bus, train or plane you take to realise that. Initially promoted as a fashion accessory, Apple soon pivoted to fitness-oriented marketing—harvesting our health data as it did so. Either way, Apple’s Watch is an incredible piece of industrial design, each edition incrementally better than the last—with 2022’s OTT Apple Watch Ultra finding a surprisingly wide fanbase outside of athletes and sports enthusiasts.

The 1st Generation was available in 38mm or 42mm and four versions: aluminium, stainless steel, Hermès stainless steel and 18ct gold. It allowed you to get notifications on your wrist, hail and taxi and make phone calls, just as science fiction predicted — but only with your phone connected. It still did more than any other smartwatch on the market in 2015. The arguments over whether Apple’s Watch counts as a “real” watch and fears it would obliterate “traditional” watchmaking proved silly.

The two coexist. Interest in watches is now at an all-time high, and Apple must take some share of the credit. Still, it didn’t get everything right. “People are carrying their phones and looking at the screen so much,” said software developer Kevin Lynch, positing his invention as a cure. Hmmm.

Tourbillons are the status symbol of high-end watchmaking—where a watch’s “heartbeat” workings are put on display in a delicate, ever-rotating carriage mechanism. Franck Muller’s obsession with dazzling mechanics meant that by 2011 he’d already produced the winner of the “most complicated watch in the world” title, twice. With the Giga Tourbillon—at 20mm, more than half the size of the entire watch and larger than some women’s watches—he set new standards in accuracy, showboating and status symbols.

As a watch that flips over on itself, sitting securely with its dial folded away and the reverse side worn outwards, the Reverso was already in a category of one. But J-LC—“the watchmaker’s watchmaker”—was only getting started. Subsequent Reverso models (and there have been many) have included one with four faces, one with shutters that wind open to reveal a nude woman and last year’s Reverso Tribute Enamel Hidden Treasures, a trio of models with tiny reproductions of “lost” artworks by Vincent Van Gogh, Gustav Klimt and Gustave Courbet hand-painted onto them. Not far off a century after its debut, the Reverso’s innovation continues to run wild.

Gérald Genta called it a “sea monster”, lamenting the engorgement of his masterwork. It was so complicated to make that six months after its launch, only five cases had passed the water-resistance test, and in its first three years, only 716 were sold. Now celebrating 30 years in the sun, the Offshore is a phenomenon: pre-dating Panerai’s revival, the IWC Big Pilot or the rise of Hublot, it can legitimately claim to have established the “big watch” trend. After the Offshore, CEO François-Henry Bennahmias won endorsements from the likes of Jay-Z and inserted Audemars Piguet into the zeitgeist via hip-hop, movies, motorsport and, er, golf.

It’s easy to celebrate the legacy of watches supplied to World War II’s Allied forces. For others, like the B-Uhr or Panerai Radiomir, it is necessary to acknowledge that they were used by Axis forces. Four German brands—A. Lange & Söhne, Laco, Stowa and Wempe, plus IWC in Switzerland, answered the Luftwaffe’s call for a navigator’s aviation watch, and the B-Uhr—also known as a “Flieger” (“pilot”) watch—was the result. Huge even by today’s standards, it is notable for the sword-shaped hands, oversized crown and simple, legible dial print. The design DNA lives on in many modern pilot’s watches, most notably IWC’s Big Pilot series.

In the 1980s quartz crisis, when cheap Japanese watches threatened to destroy the Swiss industry, makers began rediscovering the arts of complicated horology. First, time-honoured “complications” reappeared in mechanical watches; then came blends of these. Having already produced superlative watches showing key complications individually (perpetual calendar, moon phase, minute repeater, split-seconds chronograph and tourbillon), in 1991 Blancpain united these in a multi-functional masterpiece. The 1735 was the most complex automatic watch ever made. Thirty were made, and Blancpain still has a watchmaker just for servicing these.

The Monaco wasn’t the first square* watch, but it was the first-ever square chronograph, as well as the first water-resistant square-cased watch. Those are the facts. But its appeal rests on less tangible assets—its cool factor. Heuer was the first non-automotive brand to sponsor motorsport. And after Steve McQueen paired his Monaco with a Porsche 917, the endorsement proved so valuable that he’s still listed on the watchmaker’s website as a brand ambassador, despite having died in 1980. Defunct for over a decade, the Monaco’s cult appeal grew alongside enthusiasm for the 1970s’ sprucely modern design language, and it has remained popular ever since.

*technically square-ish

Something of an oddball when first launched in 1939, using a pocket-watch movement to create an oversized wristwatch with improved accuracy and legibility. Come the brand’s 125th anniversary in 1993, a graceful mid-century design was just the ticket and in the last 30 years, the Portugieser has become a modern classic, particularly in chronograph form.

All-new mainstream watch designs are vanishingly rare; great ones even more so. The original Octo carried a faint essence of the work of Royal Oak and Nautilus designer Gérald Genta, but in its ultra-thin “finissimo” form the multi-faceted case took on a distinct personality. Its slinky presence is seductive in its own right, but watch fans have been won over by the engineering: the Octo Finissimo has held seven records for ultra-thin watchmaking.

Few designs—of watches, or anything else—have proven so malleable and so constant as that of the Tank, conceived by Louis Cartier in 1917 and named after its resemblance (in overhead profile) to the machines then rumbling across battlefields in Flanders. There have been long Tanks, curved Tanks, asymmetric Tanks and more—each, with its elongated flanks and Belle Epoque dial, unmistakably a Tank and unmistakably Cartier. On the wrist of Rudolph Valentino in the 1920s, Jackie Kennedy in the 60s, Warhol in the 70s or Paul Mescal today, the Tank in its small, slim original format has never been anything other than effortlessly, exquisitely on point. And it never will be.

George Bamford, founder, Bamford Watch Department; Tim Barber, writer, Mr Porter; Alex Barter, author The Watch: A Twentieth-Century Style History; Alex Bilmes, editor-in-chief, Esquire; Nicholas Bowman-Scargill, re-founder and owner, Frears Watch Company; Maximillian Büsser, founder MB&F; Davide Cerrato, CEO Bremont; Ross Crane, cofounder, Subdial; Johnny Davis, editor, The Big Watch Book; James Gurney, editor and consultant; Chris Hall, senior watch editor, Mr Porter; Adrian Hailwood, watch business consultant; Robert-Jan Broer, founder and editor-in-chief, Fratello; Ming Lui, writer, The Financial Times; Tracey Llewellyn, editor Telegraph Time; James Marks, international head, Phillips Perpetual; Kathleen McGivney, CEO, RedBar Group; Caragh McKay, creative content director; William Messena, founder Messena Lab; Benoit Mintiens, founder, Ressence Watches; Oliver R. Müller, watch-industry entrepreneur; Tim Mosso, media director and watch specialist, WatchBox; Bill Prince, editor and author of Royal Oak: From Iconoclast to Icon; Philipp Stahl, founder Rolex Passion Report; Rebecca Struthers, watchmaker and historian; Rikki, Scottish Watches; Charlie Teasdale, contributing editor, Esquire; Silas Walton, founder and CEO, A Collected Man; Asher Rapkin, founder, Collective Horology; Dr James Nye, deputy master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers; Eric Wind, owner, Wind Vintage; Charlie Pragnell, chairman and CEO, Pragnell; Robin Swithinbank, writer, The New York Times

Originally published on Esquire UK

Rolex’s founder, Hans Wilsdorf, was onto something when he made his company logo a crown—it has remained the king of watch brands for more than a century. Its enormous brand equity is partly because Rolex gives so little away, a key to its mystique. It's frequently ranked first in surveys of super-brands in the UK. And is resident in Forbes' list of the world's most powerful brands. Ask 100 people to name a luxury watch and most of them will say Rolex.

This reputation is not mere marketing—Rolex is Rolex because it makes peerless products. We love that so many classic Rolex models were made not just to look good but for specific, adventurous purposes. The GMT-Master, for example, was created for Pan-Am's pilots. Then experiencing a new phenomenon called jet-lag—they wanted a watch that showed two time zones simultaneously.

The Submariner was made for divers. The Milgauss was introduced in the Fifties as an anti-magnetic watch for people working in power plants, medical facilities and early nuclear research labs, where strong electromagnetic fields were present. Collectors are particularly passionate about Rolex sports models, which have long been associated with explorers, adventures and athletes. In addition to the famous James Bond Submariner, an early version of the GMT was worn by US flying ace Chuck Yeager as well as several astronauts.

Rolexes lend themselves to being dressed up and down more than other luxury watch brands. The company mastered the art of the design tweak: collectors wax lyrical over a different coloured bezel here or a bigger crown there. All this contributes to their collectability and value—if you're investing in a watch, buy a Rolex. According to Christie's, Rolexes gain value faster and more steadily than any other brand.

Wilsdorf had a gift for foresight. He bet on the wristwatch very early and each of his major innovations (putting a timepiece on the wrist, making it accurate, making it waterproof and making it automatic) helped create the modern wristwatch as we know it. The downside, some argue, is that Rolex varies its designs even less than other companies: and that’s saying something for the watch world, where a "revolutionary breakthrough" amounts to a new case size or deploying a slightly different type of gold. There is no Rolex tourbillon or sign of the zodiac complication. A 2019 Submariner resembles one from 50 years ago.

The counter-argument is that you don’t go messing with perfection. Instead of visible whistles and bells, the company concentrates on research and engineering, continually update the technology inside its watches on the quiet. A more common grumble is that Rolex’s are so hard to buy right now. Demand outstrips supply, at least for some models, while the aftershocks of the pandemic on supply chains is still being felt. None of this, contrary to one suggestion, is down to Rolex restricting supply.

On the other hand, the thrill of owning a Rolex is also in the chase—if you’re lucky enough to be able to buy one, chances are you’ll remember exactly when and where you were when you did so. In this way there is every reason to believe the Rolex crown will remain firmly in place for another hundred years, and beyond.

Often passed by in favour of the Submariner, the GMT-Master or any other of its flashier cousins, the Air-King is a wonderful watch. It is also one of Rolex’ more venerable lines, launched in 1945 as an entry-level model costing less than £100, around a third the price of a Datejust. One of many “Air” watches produced during World War II to honour RAF pilots—see also the long-forgotten Air-Lion, Air-Giant and Air-Tiger—its “King” name related to its size, a then-hefty 34mm—tiny by today’s standards.

The unusual mixing of the large 3, 6 and 9 numerals and the prominent minutes scale isn’t for everyone. Rolex is known for "classic" designs, cry the detractor but we remain firm fans at Esquire. Relaunched in 2022, the Air-King now comes with a redesigned bracelet, Rolex’s latest calibre 3230 movement and a more efficient gear train, giving it 70 hours of power reserve. Bonus trivia: it’s the only Rolex that uses the brand’s gold and green colour scheme.

£6,250

Known as the “Presidents’ watch”—a mixed-blessing depending on who’s in charge, Biden took office in a Rolex though has recently become an Omega man—and still a signal you’ve “arrived” for a certain calibre of consumer. The day of the week spelt out in full at 12 o’clock divides opinion among watch snobs but it was no small technical feat when it debuted in 1956. New with an ice blue dial, a feature reserved for Rolex’s ‘950 platinum’ models, the ‘fluted’ bezel is another technical masterstroke, requiring “many years of research” to achieve in platinum, according to the brand.

£53,300

Anyone waiting for Rolex to release a completely new watch could be waiting some time. Rolex’s last new-new model was the Sky-Dweller (2012). Before that, the Yachtmaster (1992) and before that, the Sea-Dweller (1971).

Incremental tweaks to existing watch lines are what Rolex does—a business model that seems to be working out for them. It explains why news of a retooled Submariner, arguably Rolex’s single most iconic design, was one of the biggest watch releases of 2020—even though you’d need a microscope and a degree in horology to spot any updates, the first changes since 2008. (This one’s 1mm bigger, for example.) But the tweaks aren't insignificant. Inside, you get a new calibre (the 3230), an almost 50 per cent increase on the power reserve (up to 70 hours) and the latest escapement. In summing up: a fit-for-purpose 2020 Rolex, and a design classic that will outlive you.

£8,650

Red and yellow and pink and green. Also: light blue. Rolex’s new Oyster Perpetual 36 comes in five colourful dials that represent something not always readily associated with the brand: fun. Anyone thinking Rolex has either (a) lost its mind or (b) suddenly decided to chase the youth vote needn’t worry. There is a precedent here, namely the brand’s so-called ‘Stella’ dials: poppy, hard enamel designs that appeared on its Day-Dates as the world turned rainbow-coloured in the early Seventies. They’ve subsequently become hugely sought-after. Watches at 36mm have a broad appeal, and these bright designs offer a welcome point-of-difference for anyone who finds Rolex’s more traditional line-up a tad too traditional.

£5,100

A GMT Rolex is the ultimate globetrotter’s watch. In 1955, the iconic red and white 24-hour scale on the bezel was introduced. It earned the nickname ‘Pepsi’ (this black and blue version is known as the ‘Batman’). The most recent version in steel adds a state of the art movement and a dressier ‘jubilee’ bracelet. Other than that, the design has changed little in 60 years—though you can file this under timeless, rather than vintage.

£34,200

Sitting somewhere between a sports and a dress watch, the Explorer 40 was outfitted with calibre 3230, a self-winding mechanical movement entirely developed and manufactured by Rolex. As the name suggests it was made for explorers and comes equipped with Paraflex shock absorbers for a higher shock resistance. But it’s really all about the handsomely proportioned dial, with its period detail numerals and matte finish.

From £6,450

There are statement watches, and then there’s the Sky-Dweller. The most complicated watch in Rolex’s arsenal, it comes with dual time and annual calendar functions. Previously available on a leather strap or an Oyster bracelet, this newer option comes on an Oysterflex bracelet—Rolex’s patented super-comfy design made up of a titanium and nickel alloy encased in black rubber. Also new is the option of Everose gold or 18k yellow gold. An upscale traveller’s watch might not be at the very top of everyone’s want list right now. But this is a stunning piece of kit to drool over, whatever timezone you happen to be trapped in.

£34,600

In a line-up defined by headliners—the Daytona, the Submariner, the Explorer—it would be easy to leave out Rolex’s simplest offering. But if you wanted one watch that would look right with every outfit and in every situation for the rest of your life, that was distinctive without being flashy, this would be it. Though it has been around for decades, the Oyster Perpetual received an update in 2015 that included the a new 39mm case (up from 36mm), an oyster bracelet and an run of hand-finished dials in blue, grape red and dark rhodium.

£5,400

While you’d certainly be doing well if you stumbled across a vintage Daytona (Paul Newman’s 1968 model remains the most expensive wristwatch ever sold at auction, $17.8m in 2017), if you’re looking for the most advanced chronograph Rolex has ever produced then this recent version is a perfect blend of old and new. The hype, the history—everyone loves this watch.

£35,800

"Oyster Perpetual Submariner Date in Oyster Steel with Green Cerachrom Bezel and a Green Dial with Large Luminescent Hour Markers". Or, if you prefer: the Rolex Hulk. Introduced in 2010, it immediately fired the imagination of watch fans. The green isn’t just eye-catching, it’s fluid, going from bright to dark green in different light conditions.

£9,100

Probably Rolex’s most popular model. Released in 1945 to celebrate the watchmaker’s 40th anniversary, it also used the occasion to debut a new kind of bracelet—the now-distinctive "jubilee". The first wristwatch ever with a date that changed automatically, the name comes from one of Rolex’s trademark neologisms—the date changes just before midnight.

£6,800

When you're saturation diving, down in the depths of the ocean, you've got a lot of things to worry about. You're down there in a pressurised diving bell fretting about giant squid and the like. The last thing you need is your Rolex to give up the ghost. The gas mixture such divers breathe is mostly composed of helium. When helium get into the case they can start pushing it apart from the inside when the wearer returns to the surface. The Sea-Dweller is a companion piece to the Submariner, and arrived in 1967 as its beefier, techier, hardier little brother. The goal was to create a timepiece which could go deeper into the ocean. A smart helium valve in the case to release excess helium made that happen; first certified to 610 metres, then in 1978 doubled it to 1220 metres.

£11,500

Originally published on Esquire UK

Hans Wilsdorf, the company's founder, couldn't have known, when he came up with the name "Rolex" in 1908,

When founder Hans Wilsdorf came up with the name “Rolex” in 1908, he couldn’t have known the resonance that otherwise meaningless word would have a century later. By 1931, when the brand registered its iconic crown logo, he probably had some idea. Wearing those five points on your wrist is a sign, for many, that you’ve made it. And every new Rolex is a potential way to realise the dream. This year, the company introduced nine watches at Geneva’s annual Watches and Wonders show. Here are the three we’re most keen to wear, each guaranteed to capture a place in your imagination—and maybe your collection, too.

Rolex has a long history of experimenting with materials, creating its own proprietary (and jealously guarded) recipes for the platinum, gold, and steel it uses for most of its watches. Yet surprisingly, titanium joined the roster only late in 2022, when the brand introduced the Deepsea Challenge, tested and rated to an unfathomable 11,000 metres (or 36,090 feet). With the Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium—which is 30 percent lighter than the 904L stainless steel the brand uses elsewhere—Rolex offers a watch for those of us who prefer paddling about on the surface but still appreciate the combination of robust looks and an uncannily weightless feel.

Folks were shocked when Rolex announced in 2022 that it was eliminating a handful of dial colours it had introduced in its Oyster Perpetual just two years earlier. More shocking: the new Oyster Perpetual “Celebration Dial,” which brings back all those colours and throws them together on a dial made from fifty-one individual circles of enamel applied on a light-blue background. It comes in three sizes—31 mm, 36 mm, and 41 mm—and, like most fan favourites, has already earned an unofficial nickname: “Bubbles.” Rolex debuted a number of playful watches this year, but this one is the life of the party. And if you’re worried it won’t match your clothes, you’re thinking about it the wrong way. It goes with everything.

The dressiest of Rolex’s releases this year is also one of the most surprising. While the “Bubbles” Oyster is bold but grounded in a classic design, the Perpetual 1908—a 39 mm certified chronometer available in white or yellow gold and with black or white dials—is something else entirely. It feels distinct, a notable departure from the tooly aesthetics of the brand’s mainstream lines. If this signifies a new family of watches to come, that’s even more major. Rolex is not known for following trends, but the 1908’s restrained design language feels like a sage and, er, timely nod to the rising interest in subtle, superlative dress watches—even among those for whom a nicely tailored suit is a dim and distant memory.

Photography by Ryan Slack

Styling by Nick Sullivan

Originally published on Esquire US

The big news from yesterday's men's singles final at Wimbledon was not so much 20-year-old Carlos Alcaraz's inaugural win (congrats btw, Carlos) but the fact that it represented a tectonic shift in the landscape of tennis. Youth defeated grandeur, ushering in the post-Djokovician era. He has already surpassed Novak in the watch department.

Clearly, it’s not just Jack Sinner who’s bringing eye-catching accessories onto the courts, because post-match, Alcaraz slipped on a very special Rolex Daytona to accept the Gentleman’s Singles Trophy—one that suggests he has more than just a cursory eye for timepieces. It was the Cosmograph Daytona Ref. 116500LN, featuring a black Cerachrom bezel, yellow gold case and meteorite dial. (Yes, a super thin, flat disc of real, extraterrestrial rock.)

Alcaraz has previous dealings with Rolex. Following in the footsteps of Roger Federer, Juan-Martín Del Potro, and Dominic Thiem, qt the age of 18, he signed an ambassadorship agreement with the watchmaker. Last September, when he won the US Open, he was wearing another Cosmograph.

The tennis star has got to the top of world rankings for his unstoppable speed, and so it’s hardly any surprise that Alcaraz has favoured a design historically made with racing drivers in mind. (In fact, it was named "Daytona" in honour of the famous Daytona International Speedway in Florida.) This particular model earned cult status when actor and race car driver Paul Newman was seen with a Daytona 6239, a gift from his wife, Joanne Woodward, with the words ‘Drive Carefully Me’ engraved on the back.

Sadly, Daytonas are notoriously hard to come by, and Alcaraz’s otherworldly Cosmograph has been discontinued. It might be easier to just win Wimbledon, and maybe they'll give you one.

Originally published on Esquire UK

Jump starting a vintage year for the ‘king’ of the industry, Rolex has unveiled six new Daytona models, to mark the 60th anniversary of its all-conquering icon.

Announced at the Watches & Wonders fair, the watch goliath revealed that it would be adding some tasty new editions to the Oyster Perpetual Cosmograph Daytona collection that already has a waiting list as jam packed as a NASCAR starting grid.

Such is the popularily of the ‘grail’ watch timepiece, it is popularly referred to simply as the ‘Daytona’, and any new additions are released among a frenzy of interest.

This year the Daytona collection comes with the addition of six new versions and a Rolex-community pleasing new feature. The new models are in Everose gold, Oystersteel with a white face, Oystersteel with a black face, Oystersteel and yellow gold with a white face and Oystersteel and yellow gold with a gold face.

Careful not to mess with perfection, the case and dial markers have only been slightly redesigned, but the range now features Rolex’s latest 2023 movement – the calibre 4131 – under the hood.

The new versions feature restyled hour markers and counter rings, plus redesigned lugs and case sides. The platinum version comes with an ice blue dial and an oscillating weight made from 18k yellow gold.

All models now feature a transparent sapphire case back – a first for the Oyster Perpetual collection, and something the Rolex community has been keen on for some time.