The air-raid siren sounded again through the defiant city, but William McNulty refused to be bothered by it. After a long morning of meetings in Kyiv with Ukrainian partners in need of medical tourniquets and cold-weather clothing, the man had earned an afternoon nap. The air flowing through the hotel room’s open window nipped of brittle autumn, and sunlight was leaking through gray clouds; winter, as the Ukrainians liked to quip, was coming.

Fuck it, McNulty thought. The chances of getting hit by a drone strike in a city of three million people seemed low. A US Marine veteran from Chicago who’s served in Iraq and done humanitarian work in dozens of conflict and natural-disaster zones, he’s grown numb to the frequent sirens that are now a mainstay of life in Ukraine. Since Russia’s latest invasion began in February of last year, he’s traveled throughout the country, by train and van, to rural villages and the front, delivering supplies to those fighting at democracy’s edge. His nonprofit group, Operation White Stork, makes no quibble about supporting Ukraine in the war. He’s had his fill of messy wars and ambiguous purposes. He believes this is it, the real deal, the righteous cause that people of action always not-so-secretly crave.

Even altruists need sleep, though. So McNulty, 45, lay on his bed, shut his eyelids, and focused, as much as he could, on rest. Then came a strident hum. It cut through the sirens, then over them, braying and obnoxious, like a great lawn mower in the sky. It kept nearing and nearing. Then it passed directly over McNulty’s hotel.

“That was enough for me,” he recalls days later, as we drive somewhere along the black ribbon of highway between Kyiv and the port city of Odesa in the far south. He identified the noise as the engine of an Iranian-made Shahed kamikaze drone, one of many Russia has used to terrorize Ukraine’s civilian population over the past few months. He dared move only when the noise had faded out and there was nothing but air-raid siren again. To McNulty’s fortune, another target had been selected in Kyiv that afternoon in mid-October. “I headed down to the shelter room. Then we went out and ate at a nice Italian place.”

In the language of this new war, McNulty is a “volunteer,” one of roughly tens of thousands of internationals and local Ukrainians who’ve devoted themselves to supporting the resistance against the Russian military. The roles they play vary widely, from humanitarians like McNulty to social-media celebrities fundraising for military units. There are brash foreign fighters and humble food drivers and furtive gunrunners and ancient babushkas knitting camouflage ghillie suits in community gyms. Some are volunteers in the literal sense, burning through their savings to subsidize their work. Some earn a small stipend; still others are profiteers who see nothing wrong with benefiting financially amid a nation’s war for survival. It’s proven dangerous work, too—in January, two British volunteers were killed attempting to evacuate an elderly civilian. In February, American Pete Reed, another Marine veteran, was killed when an antitank missile hit his ambulance. For all the differences in type and approach, the volunteer movement is unified by a core belief that this is a fight worth fighting, that Ukraine is worth defending.

It’s a belief I happen to agree with. In late February 2022, I joined two friends, fellow combat veterans, in Lviv, in western Ukraine. We spent two weeks training a group of civilians in combat basics and self-defense. It was a frightening and thrilling and inspiring experience, and then we returned home to America, to our families, as the war progressed and endured. Others went forward. With interest and perhaps a bit of envy, I watched the volunteers of Ukraine coalesce and organize through the summer and into the early autumn. Then, this past fall, I decided to go back, for three weeks, joined by one of the other trainers from February, Marine veteran Ben Busch. We wanted to see the volunteer ecosystem that’s developed and to meet some of the people who’ve upended their lives for it.

In the White Stork van on the road, McNulty turns to look at me. He has stony blue eyes and the shaky, aid-worker gaze of those hyper-acquainted with injustice. The back of the van overflows with first-aid kits for Ukrainian army and Territorial Defense units we’ll meet in the coming days. My narrow ass is wedged between boxes of decompression needles, chest seals, and hundreds of heavy-duty shovels. Getting the shovels to the front before the winter freeze is especially important. It’s hard to dig trenches in ice.

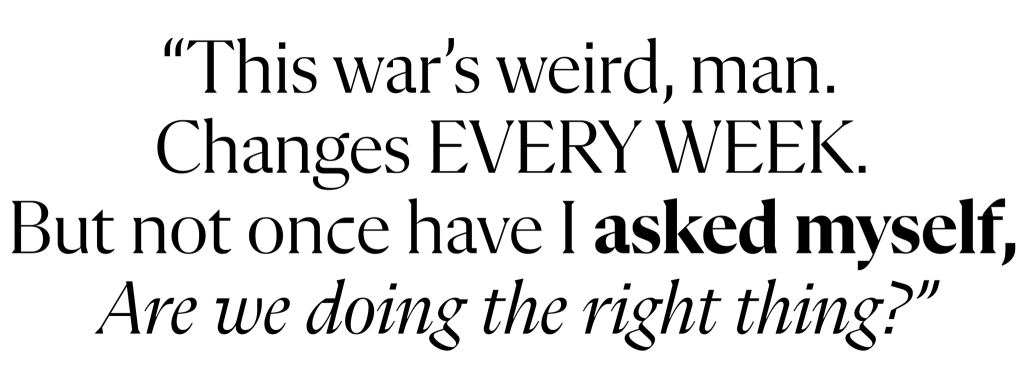

“This war’s weird, man,” McNulty says. “Changes every week. But not once have I asked myself, Are we doing the right thing?”

We settle into a mellow silence. The van rolls smooth. Harvested fields of sunflower, wheat, and corn run along our sides. A falling sun traces them with clean light. For these minutes, here, the war breathes easy. For these minutes, here, the war seems faraway and calm.

Calm is a mirage. It’s not the same as peace. But it’s also not a kamikaze drone.

The blue and yellow bands of the Ukrainian flag wave in a soft breeze. A crying mother—sobbing, really—smooths the pebbles on her son’s grave. I sneak a glance at the tombstone. Killed three months ago. An older woman tries to get the mother to stand. For many minutes the mother refuses to. A framed photograph leaning against the memorial’s cross shows a cheerful young man with big ears hugging a handsome rottweiler. I think of an American gold-star mother I know who once told me she’d trade all the benches and highway sections named for her son for one more smile. Nearby, gravediggers and a priest linger. Four empty spaces await other sons of other mothers.

When we left Ukraine last spring, it was already clear that the country would be a beacon for foreigners of various stripes. Dozens upon dozens were massing along the Polish and Romanian borders, or gathering in western Ukrainian cities like Lviv, or already making their way to Kyiv, the capital, which was under assault and a personal obsession of Putin himself.

Some of these folks were who they said they were. Some were not. Some could provide critical skills and resources to the Ukrainian people and military. Some could not.

“If you’re still here in-country, more than likely you’ve found something,” says Jeremy Fisher, a U.S. Air Force vet who runs Dark Horse Allies, a nonprofit focused on training new Ukrainian military recruits and potential draftees. Nearly all of Fisher’s trainers are veterans of NATO militaries, and some fought in the preceding months on the zero line with Ukraine’s International Legion, a military unit composed of foreign fighters. “There have been a number of yahoos that came over saying, ‘I’m a military trainer,’ but they don’t know what they’re doing.”

Fisher’s description of this natural process of attrition is echoed by Josh, an American who arrived in April and is serving in the International Legion. (Josh requested to not use his full name for security purposes.) A Marine veteran in his mid-twenties who served in Syria, Josh was seriously wounded fighting in a northeastern village in Kharkiv Oblast in late September by shrapnel from a Russian artillery round. I ask him about concerns that political extremists are going to Ukraine to gain battle credentials that they can utilise in domestic movements. “All those bitches got weeded out quick,” he says. “Maybe one or two have hacked it here and there, but if you’re not here because you actually believe in this fight, it’ll show on the ground. Fuck them.”

Everyone’s story is different. Everyone’s story is a little the same. Certain traits and patterns recur as we meet more volunteers. Most are men, though not all. Many of the younger ones served during the tail end of the war on terror and didn’t get the combat experience they’d anticipated or perhaps wanted. Some of the older ones sold their businesses or homes to sustain their work. More than a few are living off military pensions or disability checks. I stop tallying the number of divorces and separations.

One can view this as a bit sad, even pathetic. Or one can regard their coming to Ukraine as an act of courage. Here they are, in another war zone, trying to pay it forward to others, because they believe they still have more to give.

“A lot of people around the world aren’t able to drop what they’re doing and come help, even if they want to,” says a Dark Horse trainer named Dean. He’s 54, a veteran of the New Zealand army with paramedic experience, and now spends his days leading a basic-training course in the woods of western Ukraine. “I was.”

“I see this as my way to keep defending the United States—if not America exactly, then its ideals, what it’s supposed to stand for,” says Max Cormier, McNulty’s deputy at White Stork. Cormier is 28, a former US Army airborne infantry officer with a surfer vibe, from the Tidewater region of Virginia. He appreciates the straightforwardness of their humanitarian work and the plainness of his directives: “Don’t crash the van; deliver the goods.”

Cormier got a residency permit that lets him stay in the country for longer stretches to better help with the war effort. “A lot of people come here looking for meaning,” he says. “Some of us have found it.”

We’re at a seaside restaurant in Odesa, watching dusk spill over glassy blue water. Skull-and-crossbones signs speckle the view; the beaches here were mined in case the Russian naval infantry tries to seize them. A few diehard locals still stroll across the sand with exactness. War will not stop their sunbathing. Cormier checks his phone. A delivery of medical supplies the next morning needs to be coordinated. And a post-work Tinder date before they push east is not out of the question. War can’t stop Tinder, either.

White Stork has delivered more than 22,000 modern first-aid kits since last spring. As we travel the southern shoreline from Odesa to the Mykolaiv and Kherson regions, I see some of the Soviet-era kits that they’re replacing. One is stamped 1988. It’s eleven years older than the soldier carrying it.

Podil District, Right Bank, Kyiv

Souped-up four-wheel drives lacquered in camo paint rumble through every intersection. A giant billboard featuring the Rock drapes from one building, encouraging people to buy Under Armour. Nearby, there’s a banner demanding the freedom of the imprisoned Mariupol Defenders. There’s a moon somewhere in the sky but no one can see it.

To the hotel bar we go. There’s Wilson, sipping on a Jack and Coke, making conversation. He does this every night. Former mil, he says, an engineer by trade, and he’s putting together a crew. For what? He’s not comfortable talking details.

One crew member is a South African named Black Pete. Black Pete gave himself that nickname to differentiate from a Brit known as White Pete, though Black Pete is also white. “It’s funny to call myself Black Pete,” Black Pete says. He’s already drunk and bothering the clerk tasked with tending the bar. Later, a woman joins Black Pete. She appears to be a sex worker; he keeps insisting we call her his “associate.”

Nazar, our interpreter and guide, decides this scene isn’t for Ukrainians. He excuses himself to call his wife.

A wounded legionnaire drinks with us. He raises his sweater without ceremony and we gaze upon his fresh wounds and listen to his war story. It is what young soldiers and old soldiers must do together. It is a good and true war story, and we buy him another round and toast to his bravery. Everyone’s trying hard to ignore Black Pete, even his associate, because he is distractingly loud. My friend Ben talks with Wilson in one corner. I huddle with a jovial Australian with a Santa beard. “Bullets are flying; the women are stunners,” he says.

“This is the dream.”

The obvious good. The clear purpose. The value of empowering those on the ground level. These ideas come up over and over again in meetings with volunteers. Large operations like World Central Kitchen and UNICEF maintain a robust presence here. But most of the thousands-strong volunteer network is made up of much smaller organizations, consisting mainly of Ukrainians, a cobweb of decentralized connections that relies on personal referrals and loose, logistical partnerships.

Sometimes volunteers find their group; sometimes the groups find them. Take Ihor, a middle-aged Lviv man who went to Bucha, near Kyiv, last April, right after the city was freed from Russian occupation, loading up a van with generators and fuel and driving straight into the maelstrom. What he saw there—rape victims, bodies being eaten by dogs—led him to quit his job and become a full-time supply driver for various charities. “I’ve seen parts of my country I’d never been to before,” he says. “And now I know war is worse than the books say.”

Then there’s Ekaterina, a fitness director in Kharkiv who told her mom they weren’t evacuating no matter what and who now oversees the delivery of new and repaired vehicles to frontline units. There’s Alena in Irpin, a leafy, upscale suburb of Kyiv where the invasion was pushed back last spring. A fire-support captain, she fought in that battle. She says two things saved the Ukrainian military in those messy, confusing days: relentless artillery from Kyiv and “regular people in the community who grabbed a gun and fought.”

Mykolaiv, in the south, is the first place we visit where the war feels like a tangible, active force. Artillery booms in the near distance. People here are twitchy and tense. The front line lies only a few kilometres from Mykolaiv’s city center. It’s moving in snailish increments toward Kherson, two hours east, but moving. Kherson will be liberated in about two weeks. But now there are rumours the Russians may blow the river dam, flooding Kherson, rather than see it taken back by Ukrainian soldiers. Or that they’ll deploy tactical nukes or airborne Spetsnaz or suicidal Chechens.

“There’s some electricity now; it’s not so bad,” Oleksandra Blintsova says of her native city. “When it was total black, I was walking around with a shovel to protect myself.” Blintsova, 38, volunteers for Heroes for Ukraine, a local nonprofit that emerged in the aftermath of the Russian invasion. She coordinates medical training for civilians, serving as an interpreter and assistant instructor for visiting military veterans who teach first aid and combat medicine. While walking us through Mykolaiv’s Chestnut Square, she points to some cruise-missile ruins in the square’s interior. She says locals call it a gift from the Moscow Diplomatic School. “We will always laugh at them,” she says. “Then they can’t control us.”

During the first night of the invasion, February 24, Mykolaiv came under heavy shelling. Blintsova’s husband had already been mobilized, so she brought their two young children, her mom, and an elderly neighbor to a shelter. There were maybe a hundred people hunkering there, and to both project calm and maybe even find some herself, she and a couple others started knitting together camo nets from old T-shirts and blankets. What began as a small act of defiance quickly turned into something more pragmatic. After camo nets came pillows and boot insoles, then ghillie suits. One elderly babushka proved especially adept at rolling homemade cigarettes for the local fighters.

In the subsequent weeks, Russian soldiers breached the outskirts of Mykolaiv, and some of their scout units penetrated the city proper. They couldn’t hold it, though. By mid-April, all Russian ground forces had withdrawn from attempts on the city. But the war was still there, just kilometres away, and many Mykolaiv men like Blintsova’s husband were still fighting it. So the supply center kept at it, homemade cigarettes and all.

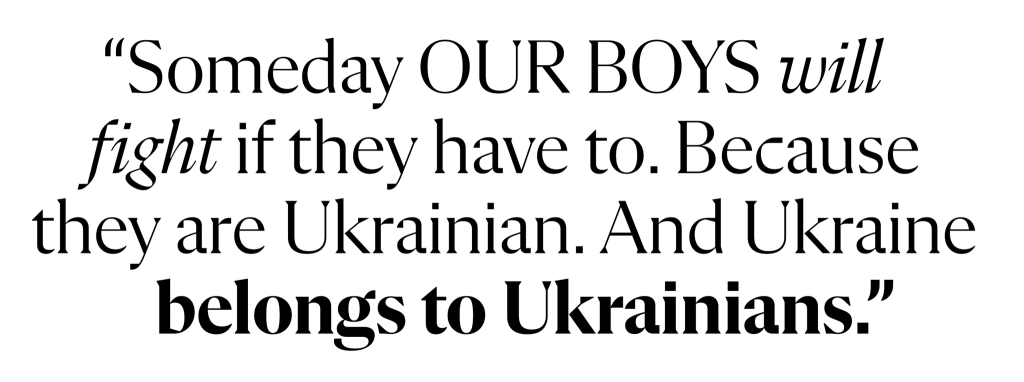

Blintsova takes us to a nearby school where a friend works as the principal. Most of the kids do remote learning, though a few classrooms have students in them, each child seated at a desk a brazen act of normalcy. “Our children say three words every day,” the principal says. “Peace, country, victory.”

Many experts on global politics believe that Putin has been hell-bent on this invasion, or something like it, for years. I can’t help but wonder, there in the school, if he’d perhaps have reconsidered had he a better inkling of Ukraine’s entrenched national pride and identity.

“My husband says he fights the Russians so our boys won’t have to,” Blintsova says as we depart the school. “And maybe he’s right. I hope so. But someday our boys will fight if they have to. And so will their boys. Because they are Ukrainian. And Ukraine belongs to Ukrainians.”

Irpin, Kyiv Oblast, Hero City of Ukraine

“The last Ukrainian checkpoint was right there, by the mall. Giraffe Mall. Silly name. This is exactly how far the Russians got.”

I’m tagging along on a guided tour for Western think-tankers and national-

security gurus. We’re driving to the places made infamous by occupation and murder: Irpin, Bucha, the airport. To learn. To nod and consider. To bear witness to bravery and ruin and futility and aftermath. There’s enough of a cranky soldier still in me to find it all a bit ridiculous. The actual war’s far to our east now. But hey, they came, I think. How many of their tribe never dare leave air-conditioned offices?

Someone asks about the Street of Death. Our guide shudders. “You can go there,” she says, pointing down the block, behind a set of damaged apartments. Months ago, she fought in Irpin. She knew the Street of Death when scorched cars and bodies blotted it. “I will not.”

“We’re good, I think,” someone says. No one objects. It’s an interesting thing, watching a woman’s combat bona fides burn holes into a cluster of male egos. We return to the cars and caravan to the next spot.

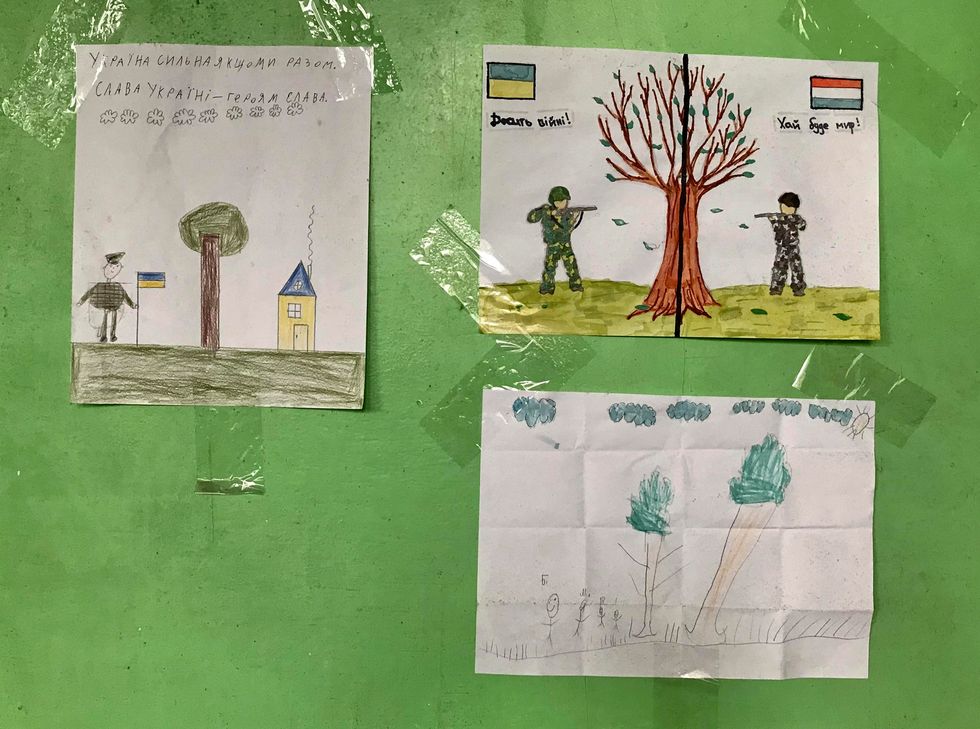

JOURNEYS THROUGH A NATION AT WAR

Over three weeks last autumn, Matt Gallagher, joined by fellow veteran Benjamin Busch and their interpreter, Nazar, traveled across Ukraine to report this story. They saw firsthand that while the battlefields illuminate one facet of the war—the stalled advance of Russia’s invading forces—they obscure another: that the entire nation, across social, economic, and cultural lines, is engaging in the fight for its freedom.

Let us speak plainly: There’s something odd about volunteering for a foreign war. The Americans who fought for loyalist Spain in the 1930s were later labeled “premature antifascists” for their efforts (a term they adopted as a badge of pride). Even after Pearl Harbour, fewer than 39 per cent of U.S. troops who served during World War II volunteered for it. More than 61 per cent were drafted.

Not every international we encounter in Ukraine is a lost soul. But some are. One person who requests anonymity goes into great detail about catching his wife in bed with a neighbour and buying a one-way airline ticket to Poland the following day. “Can’t lie,” he says. “It was the most freeing fucking feeling.”

Redemption tours take many forms.

Sam Cook, 45, has lived in Ukraine since 2018. He graduated from West Point, commanded a cavalry troop in Iraq, and first came to Eastern Europe to run a tech company. He’s since started Borderlands, a historical foundation, and now teaches a course on war and storytelling at a Kyiv university. Seeing this new wave of internationals discover the country he adores, he says, has been “a bit of a time warp.” Before the invasion, he and his Ukrainian wife were planning on raising their family in Kyiv. Nothing since has changed that vision, not even a missile recently striking a city park 600 metres from their apartment. “It’s kind of like the old Wild West,” he says. “People don’t care who you’ve been, just who you are now and what you’re doing.”

What about those with families back home? Only two people I meet say that aspect of their life continues to hold strong: Martin Wetterauer, chief operating officer of the Mozart Group, a donor-funded military-training organization, and Stephanie Willis, who works for New Horizons for Children, a charitable fund that specializes in supporting displaced Ukrainian orphans.

Wetterauer points to a long career as an officer in the Marines to explain his marriage’s success. He calls home more often from Kyiv, he says, than he did during various deployments across the Middle East, Africa, Bosnia, and beyond. (I later learn he may be home even more: In early February, the Mozart Group will reportedly collapse amid allegations of financial mismanagement.) And Willis is able to rotate back to the States every four to six weeks, which comes with its own challenges. “Some people don’t even realize the war’s still happening,” she says. “That can be a lot.”

Another American I meet, also helping with orphans, is less a volunteer and more a benefactor. Amed Khan, 51, travels through the conflict-ravaged country looking for causes he believes in. He’s described to me a few times as “one of the most important Americans in Ukraine,” and not just by people hoping for a taste of his financial support. There’s a rumor Russia has put a bounty on his head. Khan demurs when asked about it. He doesn’t deny it, either.

“This is not a matter of evil versus good. This is evil versus normal,” he says. “It’s literally the defense of freedom.” A veteran of the Clinton White House, Khan later founded a private international investment firm and proved quite successful at it. In 2011, he purchased one of Andy Warhol’s celebrated Mao portraits, the one shot up by actor Dennis Hopper, for a cool USD302,500. He detests the slow bureaucracy of large-scale humanitarian work, so he goes out and gives directly.

“If you fashion yourself a philanthropist, this is what you need to be doing,” he says, sharing anecdotes of rich and famous acquaintances he’s cajoled into donating to war-relief efforts. We meet him in a fancy Odesa hotel, where he’s staying a couple nights after working on the repairs to an area orphanage damaged by Russian shelling. A few weeks prior, he spent time in the recently liberated area of Kupiansk asking locals what they needed. There he met an abandoned German shepherd he took a liking to. No one there seemed in a position to take the dog. Jack Khan, so named to get the pet passport approved, now lives in Italy with opera singer Andrea Bocelli.

There’s world-weariness in Khan’s laughter and self-deprecation. He’s seen much more than your average rich banker has. There are also flashes of an old, hidden idealism. He’s helped to house Syrian, Iraqi, and Rwandan refugees over the past two decades and to evacuate thousands of Afghans since the country fell to the Taliban in 2021. “I’m no fan of the military-industrial complex, but this is something that has to be done,” he says. “There’s a genocide going on.”

His money and connections make Khan different from most internationals in Ukraine. But there are a few commonalities. No partner or kids back home to complicate his globe-trotting or patronage—“What kind of jerk would I be if I was doing this with a family?” he says. And then there’s this:

“They have something called a society here,” Khan says. “Nothing is bigger than it. It reminds me of the America I grew up in. It reminds me of an America I miss.”

Not every foreigner in Ukraine, though, has come to help orphans.

Dnieper-Bug Estuary, Northern Coast of the Black Sea

Anight on the water with drone hunters. “We have NATO lasers and American night vision,” one says, “but we do better without them. We get the radar from our phones. We listen.” He taps his ear. “Then we shoot.”

Slapdash as fuck, I think. But it’s hard to argue with success: This Territorial Defense team of a dozen has shot down three Russian drones over the past week, they say. They’re armed with ten rifles, two pistols, and a Browning machine gun mounted to the back of a pickup truck.

I ask what they need. Too many supplies, they say, not enough weapons. What kind? All kinds. They have questions for me, too. Have I met Jennifer Lawrence? (No.) Has Elon Musk’s brain cracked? (Probably.) What the hell is going on with American politics?

“Our president is a Jew. Our governor is part Korean,” one says through the shorn dark. “How can we be Nazis? Who are these people that get tricked?”

Some indeterminate time later—minutes? hours? down the nocturnal well, who can say?—the lieutenant barks out in coarse Ukrainian. The drone hunters spread across the position like a wave, guns and ears arching toward the sky.

Shaheds are inbound.

Seconds drip into the still. The air smacks of chilly sea. Someone fidgets with the straps of their plate carrier. Someone else charges their rifle, and the black magic of the gun slams forward. There’s that clarity of purpose again, I think.

War is many things. An abomination. A proving ground. And also: a business. There’s money to be both made and found in Ukraine. War’s layers of white, gray, the beyond gray—there’s green in it all.

For example, the HIMARS. Anyone who knows anything about Ukraine knows this mobile rocket-launcher system changed the trajectory of the war upon its arrival last summer. (“The sense of martyrdom went away,” Cook, the Borderlands founder, says. “It gave them hope that they could win.”) The US government supplies HIMARS to Ukraine, but it’s Lockheed Martin that makes them, and not out of the goodness of its heart.

There’s no clean binary between a pursuit of profit and genuine support for a free Ukraine. Yes, there are lines, moral and legal. Some are obvious, like US International Traffic in Arms Regulations. Others are up to the beholder.

Steven Moore, fifty-four, moves both in volunteer circles and on the business side of the war. A former political operative who’s been the chief of staff to a Republican congressman, he was between jobs and recently separated from his wife when Russia invaded. He had friends in Ukraine and wanted to help. Five days later, he established a safe house for fleeing civilians along the Romanian border. That safe house soon grew into a supply operation, and now Moore heads the nonprofit Ukraine Freedom Project.

When we speak over lunch at a Crimean Tatar restaurant in Kyiv, the group’s focus has been food deliveries to people in need in Kharkiv and Donetsk Oblasts—more than two hundred tons’ worth.

“I want to stay here,” Moore says, “because I feel I’ve been making an impact.” One way he’s done that is lobbying. When a body-armor company run by a friend of a friend in Lviv ran into issues with its steel supplier in Sweden, he flew to Washington “and sat down with the lobbyist for the steel company,” he says. “She got me connected with the right people. Now these guys have a steady supply of steel.”

Moore is also a cofounder of HighCat, a German start-up that’s currently testing (and marketing) combat drones designed to attack armored vehicles and artillery pieces with munitions from above. “I’m the guy that’s looking for funding.”

War enterprise with wing tips and half Windsors: a proud tradition. (Months later, after this story went to print, Moore emailed to say he and the German engineers had parted ways.)

The conversation reminds me of something a Ukrainian soldier told me a couple days prior, in a destroyed village near Kherson: “War is math. More dead Russians means more alive Ukrainians.”

There are the aboveboard hustles, and then there are the others. Such as: A prominent international trainer in the east establishes contacts in a local unit. He exchanges training for captured Russian equipment, which in turn is traded for new Western gear that can be sold. This all happens without official governmental sanction, Ukrainian or Western, because what kind of fool self-reports? And hey, goes the rationale, it’s peanuts in the grand scheme.

At the expat Irish pub in Lviv, I meet someone from a group I’ve been told repeatedly transports weapons for various militias. He laughs when I try to get him to agree to an interview. It’s not a friendly laugh. As a peace offering, he sends over a pricey whiskey.

“On me,” he says with a wink from across the bar. “I make more than journalists.”

Ukraine’s foreign minister said last March that nearly 20,000 soldiers from more than 50 countries had volunteered to join the Legion. Whether that tally was accurate at the time, it is almost certainly inflated today, as legionnaires can come and go in a way Ukrainian fighters cannot.

A tangle of semi-independent militia groups also populate the terrain. Some are Ukrainian only, some international only, some mixed; I’m told that all are task-organised to Ukrainian military commanders. A few hundred Americans have volunteered for direct action, best I can gather, perhaps more. At least eleven are reported to have died as of press time. A US Army vet killed in May, Stephen Zabielski, was fighting with a group called the Wolverines, according to Rolling Stone. Another Army vet, Joshua Jones, was killed in August; he’d fought with both the Legion and a Canadian-led militia known as the Norman Brigade. (Hopping units is not uncommon for international combatants.) Two other American vets, Alexander Drueke and Andy Huynh, were captured by Russian forces in June while fighting with yet another international unit known as Task Force Baguette. They were freed in September in a prisoner exchange.

Then there’s the confusion of the actual battlefield.

“If the Russians were anything other than hot garbage, we would’ve been fucking wiped out,” says Erik, a US Army infantry veteran in his early thirties. (Erik requested to not use his full name for security purposes.) He’s recounting an operation east of Kupiansk, a small city in northeastern Ukraine that was liberated in September. When we meet, he and his friend Josh, the Marine veteran in his mid-twenties, are recuperating from injuries in Kyiv.

Both men arrived in Ukraine last April. They soon linked up with a squad of international military vets that was attached to a larger Ukrainian unit. After a few months of support operations, Josh says, “we figured out we were cash cows.” He explains: “The more foreigners you have in your unit, the more you can sell that to someone”—investors, journalists. “?‘This is why I need all this gear; I have the guys who can use it.’?”

The group walked, shopping themselves as a singular entity until they found a Legion commander who promised to use them for combat missions.

They got what they wanted in late summer, in and around greater Kharkiv. They found it a different type of warfare than they’d fought in Afghanistan or Syria. Suppression weapons like rockets mattered tremendously. Artillery and air support went both ways now. Night reconnaissance proved especially interesting, with one pair of night-vision goggles for the entire squad of twelve.

I ask how many in the Legion are capable fighters. I expect a low number in response but not as low as I get: 10 per cent. “It’s a zoo,” Josh says. “We did good work, but let’s be real: We’re grunts driving civilian cars.”

September’s eastern counteroffensive presented an opportunity for the Legion’s regular line battalions to prove to Ukrainian senior command they could be relied upon. It’s the same counteroffensive that brought Josh and Erik to Kupiansk and a little village beyond it known as Petropavlivka.

While clearing the village on foot, they came across a Ukrainian patrol that had pinned some Russians in a one-story building. Erik and a Ukrainian counterpart broke down the front door and tossed in some grenades, then Erik entered. Two grenades met him inside in return, spraying his body with fragmentation. A Canadian legionnaire dragged him to the bathroom, near the entryway, where they were able to maintain something like security because of the angles of the building. The Canadian applied two tourniquets—one to Erik’s leg, one to his arm—in the bathroom while the rest of their squad tried to figure out how to get them out.

A Russian 122mm artillery round solved the dilemma for everyone. It landed near the building, putting the small-arms gunfight on pause. In the stunned aftermath, “my squad leader provided cover from the doorway while two guys drug me out,” Erik says. The round also sent shrapnel screaming along the building’s side, where Josh’s team “ate the artillery blast.” At that point, he says, he started “poking myself and finding holes of blood.”

As for the trapped Russians, if any survived the artillery round, they were soon dispatched by a Ukrainian tank. Seven enemy bodies would eventually be pulled from the building’s wreckage.

Both men were medevaced. Josh immediately underwent surgery to remove shrapnel from his liver and lungs. Erik says he’s still pulling fragment slivers from his leg and back. They begin to argue over minor details of the gunfight and their evacuation, who was where and when. They decide to settle matters by watching footage of the battle from one of their phones. Turns out, a drone had recorded most of it.

“Like watching yourself in a dream,” Josh says. He presses play.

Freedom Square, Kharkiv

On the drive east, our interpreter Nazar shares news: His wife is pregnant. Joy amid ruin. He seems as starry-eyed and unprepared as any other new father, as it should be.

I can’t be the only one in our rental car who starts thinking of the Ukrainian children being abducted and taken to Russia for forced adoptions.

We arrive to Kharkiv at night, walk the streets looking for a place to eat. The entire city is dark, traffic sparse. I have the sense we’re being watched as curfew looms.

Daylight in the grim city brings half buildings and rubble porn. We visit a mostly empty Freedom Square and guess at where the massive Lenin monument once stood. Protesters pulled it down nine years ago.

We return to the car and drive around. Artillery holes puncture groceries and proud little homes. A babushka rakes leaves. We stop. Ben takes some photos. Then we keep going. The potholes grow. The impact craters multiply.

We enter the tiny village of Tsyrkuny, northeast of Kharkiv and about 13 kilometres from the Russian border, to the sound of hammers banging on wood. Restoration is underway, though it’s hard to see how the locals even knew where to begin. Trench lines run beside the dirt roads, and deep craters spot the drab landscape. Some houses appear untouched. Others look like a demented god reached down and ripped them apart just to see what would happen. Heavy artillery thumps away in the near distance, steady as a heartbeat. The occupation may have ended here but the war hasn’t.

Post-invasion, Tsyrkuny became a refit area for Russian troops attempting to push into Kharkiv. They stayed until May, when the area was liberated. Artillery barrages continued through August, going both ways, and sporadic shelling still happens. The bleakness remains, but the worst has passed.

This is the end of the road for all the work of all the various volunteers, where all the relief effort is supposed to effect change. Some of it has. Residents speak of deliveries of food and blankets and generators. Perhaps it’s fitting they can’t name the exact volunteer groups that have come.

Viktor, 47 at the time, and Natalya, 44, have lived in Tsyrkuny their entire lives. They raised both their sons here. We find them in their home’s courtyard with her mother, Hanna. They’re trying to figure out what to do with their large garden for the winter. It needs tending, but so much else demands their focus.

When the Russians first arrived in Tsyrkuny, the Ukrainian couple stayed because of her mother. Within a matter of days, one of their vehicles had been stolen and their house searched—local separatists arrived, too, and were looking for private guns. Computers were being taken from neighbors’ houses, cell phones confiscated and SIM cards removed. They looked around at what was happening and decided they couldn’t linger. They packed up their other car and chanced a back-road drive to the city.

They made it. Not everyone did. One of Natalya’s cousins was seized by the occupiers last spring. No one has heard from him since.

When Viktor and Natalya returned to the village in May, they found their home had been turned into a dump. All their windows and mirrors had been broken. Any electronics and other valuables left behind had been looted, and human feces covered the floor of one bedroom. Even the potatoes stored in the basement were gone.

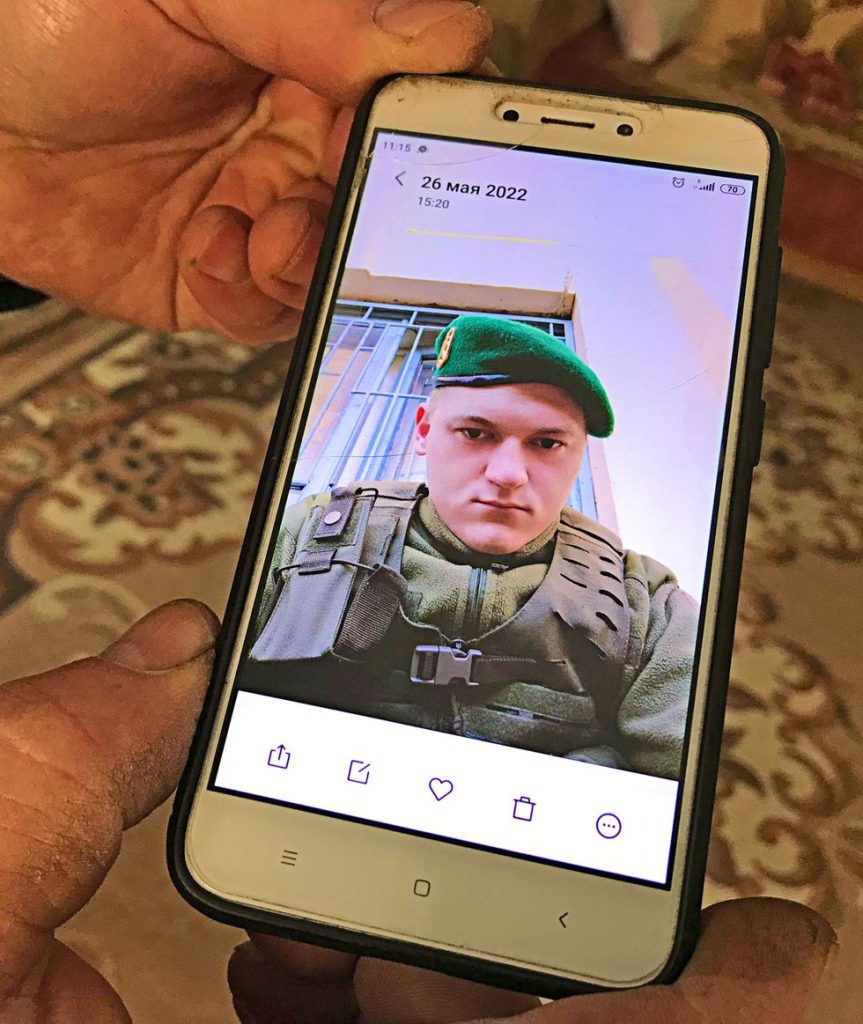

None of that mattered, though, not compared with their family’s most significant loss. On the fifth day of the invasion, their older son, Aleksander, 25, a border guard, died while on duty.

“We are not political people. Before the war, we avoided all that,” Natalya says. For most of our time together, she defers to her husband, but on this issue, she steps forward with resonant rage and sadness. The circumstances of their son’s death remain murky, but there’s no doubt she holds Russia responsible. “Now we hate them. We will never get over it. They broke our lives.”

Viktor works for the gas company, and Natalya hopes to resume her home flower business once spring arrives. As we’re shown around the village, Viktor stresses they’re better off than most, that they consider themselves blessed. Their faith has been tested, he says, but they know their boy is with God now. That matters to them. It matters a lot.

Their younger son is 17, studying in Kharkiv to be a history teacher. “What if he’s drafted to fight, too?” I ask.

“He’ll be a history teacher,” Viktor says.

There’s still no electricity in the village and they’ve been told not to expect any through the winter. Viktor insists we follow his steps exactly; mines have been found in yards, and a neighbour down the street lost an eye to a Russian booby trap while cleaning out his own kitchen. A washing machine sits along the main dirt path, conspicuous as a zit, taken from a house but left behind in May by some panicked Russian. No one’s claimed it, Viktor says. Not everyone has returned yet.

Hanna approaches Ben with a handful of shrapnel fragments shaped like daggers. They’ve been wrenched from the walls and doors, remnants of the artillery pit behind the family garden. “We hear some don’t believe,” she says. She means Russia’s war on civilians. “Take these and show them.”

Viktor and Natalya are rebuilding the best they can. It’s a choice they make anew every morning. They’ve restructured their emotional lives, too, around their grandson, Aleksander’s little boy. They already have a crib in the room he’ll stay in once the house is done.

The couple at first decline to share their last name. Which is normal enough. Before we depart, though, they come up, together, and say they’d like their son’s full name to be published. To honor him, they say.

His name was Aleksander Shmal’ko. He was a son; a husband; a father and he died defending Ukraine from the invaders.

Old Town, Lviv

My last night in-country. One train between here and the security of NATO skies. Ritual is important, so I go back to the Irish pub and order a pint.

A young American and a one-armed Brit sit nearby. They ask who I am, where I’m from. I’m sick of veils, so I tell the truth. “Hey, I’m from around there, too,” the young American says. Turns out, he’s the much younger brother of an old friend.

It’s absurd happenstance. It’s also not. Certain people come to Ukraine. I should know that by now.

I remember this young man as a boy. He’s grown up, a military veteran himself, here to conduct medical training. He needs better supplies, though, he says. “There are some folks who can help with that,” I say.

His reasons for being here are both unique and universal. His colleague served in Mariupol. We spend the rest of the evening discussing the battle fought there and the battles still to come.

“How long you here?” I ask them.

Only now do I realise the futility of the question.

Photography by Benjamin Bunsch

About the Author

Matt Gallagher is the author of the novels Empire City (2020) and Youngblood (2016), a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He’s also the author of the Iraq war memoir Kaboom (2010) and lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with his family.