If you haven't heard, the streaming-verse is about to gift us yet another video-game adaptation: Fallout, which will debut on Prime Video later this month. Its source material is a role-playing game (RPG), in which the story unfolds based on the player's decisions. It's a choose-you-own-adventure style of freedom that's largely only found in video games—which, obviously, presents a challenge once those elements are removed.

So the best way to experience everything that Fallout offers is to simply play the games. Beginning as a two-dimensional PC title, the series now plays as a modern 3D first-person shooter. It's equipped with everything that fans of Bethesda Softworks—the studio behind The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim and Starfield—know and love. Player freedom is vast, and gameplay systems are easy to understand. All the player must do in this postapocalyptic world is survive in the Wasteland by any means possible. Throughout five mainline titles and three spin-offs, the Fallout series still boasts a strong community. But there's only so much I can explain about Fallout in words alone. The only way to truly understand what makes the series so great is to jump in yourself.

Way back in 1997, the first Fallout game set up everything that would delight fans for the next 27 years. But just like early entries in many long-running gaming franchises, Fallout’s top-down RPG style doesn’t exactly inspire the shock and awe of modern 3D titles. Still, Fallout told a compelling story—which is based in the year 2161, as nuclear fallout forces humanity to take shelter in Vaults. Venturing out into the Wasteland, the player searches for water while they fight the Master and his army of Super Mutants. (Don't worry: Spend a few hours with the game and you'll have its lexicon mastered in no time.)

Set 80 years after the original Fallout, Fallout 2's story follows a descendant of the first Vault Dweller as he sets out to create a Garden of Eden for his Vault. While Fallout 2's gameplay and look doesn't stray too far from those of its predecessor, the game features more environments from around the world.

Fallout Tactics—the first spin-off in the Fallout series—threw everything you thought about Fallout out the window, creating a multiplayer turn-based RPG with linear story campaigns. Instead of playing as a Vault Dweller, users control six members of the Brotherhood of Steel, an in-game technology-focused faction, as they conquer the Wasteland and expand their territory.

In 2006, open-world games—such as The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion—sold so well for Bethesda that the studio took the formula and (controversially!) applied it to the world of Fallout just two years later. Turns out, everyone loves an open world once they actually play it. The game received universal acclaim.

Set in the ruins of Washington, D.C., the game has your Vault Dweller once again entering a wasteland. But this time you're equipped with first-person-shooter capabilities and 3D exploration. Fallout 3 also introduced a new (now classic) combat system, which allowed players to target specific areas of the body to disarm opponents, slow them down, or even go for a quick headshot.

Fallout: New Vegas is considered by many fans and critics to be the best entry of the series. Building on the success of Fallout 3, New Vegas places players in a three-way faction war where gameplay choices drastically affects the story moving forward. From altering where they explore to who they fight for, New Vegas allows players the greatest freedom in a Fallout title to date. Obsidian developed the spin-off title in just under a year before eventually going on to make the celebrated 2019 RPG The Outer Worlds.

Functioning as a free-to-play construction game, Fallout Shelter allows players to build and manage their own Vault. Though the mini-game features some annoying microtransactions, the spin-off expanded the world of Fallout and integrated a complex system of resource management.

Fallout 4 shocked many fans of the long-running series when it arrived in 2015. Abandoning the franchise's traditional RPG elements for a more streamlined story, the fourth numbered Fallout entry functions more as a shooter (and looter) than it does a traditional Fallout RPG.But even without the freedom of choice of Fallout: New Vegas, Fallout 4 still incorporates an expansive base builder and more weapon enhancements than I’ve ever seen in a video game.

For all the bugs and disappointments that surrounded Fallout 76’s rushed launch, the massive online multiplayer spin-off eventually garnered a rich community. One group of players—collectively known as EATT (Establishment of Appalachian Taste Testers)—hunted other players and used the game's bizarre cannibalism mechanics to eat them. Another community even put an NPC on trial and let the game's users decide his fate. Even if you remove traditional RPG elements, gamers always find a way!

Originally published on Esquire US

“It is frustrating that people still think of board games as being like Monopoly, just going on forever and ever, with players sat there circling the drain until it’s over,” laughs Chris Backe, “when there’s a new generation of board games that allow us to explore aspects of ourselves we don’t generally get to explore. It’s like the movies or novels, only with games you’re not a watcher but a participant. With games, we get to step out of our skin”.

Backe is a rare beast: he’s a full-time board game designer, always working up 20 or so new concepts for his company No Box. He’s testing them, seeing what works and what doesn’t, and over recent years seeing his industry enjoy a huge revival—to the tune of USD16b in annual sales, thanks in part to the pandemic. Over his years in the business, he has concluded this: it’s not that people like to play, but that they need to play. And not just in structured ways, as with games or sports, but in manners that have no purpose at all beyond the pleasure of doing them. We’re not just talking about children here; we’re talking about grown-ups too.

“I’m a strong proponent of the idea that adults should play, by which I mean play that is defined as self-chosen and self-directed, not driven by coaches, not something you have to do,” says psychologist Peter Gray, author of Free to Learn and one of the world’s leading scholars of play. “All play in a sense has rules, maybe handed down [from] generation to generation, sometimes implicit, sometimes just made-up on the spot. But we all need to play more. Play has made us what we are”.

And not just us. All mammals play, from dolphins to dogs. One theory proposes that those mammals are capable of using objects as tools. Like a monkey using a stone to break open shellfish, for example, or the first instance when a stone is used as a toy. Utility came later. Others stress how, despite its energy expenditure, and even the occasional injury, natural selection has not weeded play out, as might be expected.

In part that’s because play is often a process of exercise or stress relief, both good for us. But it also has a much more important role. One key idea—first proposed by Karl Groos in his The Play of Man (1901)—is that play not only allows the nervous system to develop ready for certain activities later in life but it also functions as a kind of practice. Of those skills required for survival, learning to cope with unexpected events, and preparation for doing things as a competent adult.

The skills and values explored in play can be specific to a child’s culture—Groos suggested the likes of hunting, skiing, canoeing or horse-riding. It seems that children’s readiness to play at these is instinctual; they observe and mimic without being prompted. The skills can also be more universal. Play, for example, is often social—first is the need to decide together what and how to play, so cooperation and communication are essential.

In fact, animals that are more dependent on their group for survival tend to play more, with, as Gray argues, hunter-gatherer societies positively suffusing nearly all they do with play. From religion to work and ways of settling disputes, all the better to suppress any drive to dominate. In play, you have to learn to control your impulses, like in play fighting where you’re almost hitting your opponent but never actually. It’s as much mental as physical too. Being self-directed, play also fosters creativity, imagination, experimentation and independence.

It’s why, argues Rene Proyer, professor of psychology at the Martin Luther University in Halle-Wittenberg, Germany, while some of us play in more obvious, more socially acceptable ways—he cites those who play video games, use colouring books for “mindfulness” or who build the complex sets LEGO created specifically for adults (“Adults welcome,” as its ad has it)—we all tend to play in one way or another. Humour, fantasy, daydreaming, sexuality all offer forms of play, as does language, as the very phrase “wordplay” suggests. People often use play as a means of getting through repetitive tasks, inventing challenges for themselves, he notes.

“[If you play with children] you soon learn that almost anything and everything can be play. But, in a way, adults are more free to play because our worlds are larger [than children’s],” Proyer suggests. “And there are good reasons to continue to play as adults, even the opportunity it brings for continued learning. But the easiest answer to the question of why adults should play—and the most correct one—is that it’s fun. Play can be used to maintain alertness, or to keep you in the moment. It’s through play that you can enter a ‘flow state’.”

This idea, of being fully immersed in a feeling of energised focus and enjoyment, is now more commonly cited about sport or the production of art—but it was first proposed, by the psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi in 1990.

And yet the evolutionary necessity of play has long been side-lined, even denigrated. Sebastian Deterding, professor of design engineering at Imperial College, London, and a researcher in playful design, says play got in the way of industrialisation and its need for reliable labour. Capitalism saw play as a waste of time; play became associated not with positivity but with the Bacchanalian wildness of festivals.

“Even in the Medieval period kings would complain about peasants playing cards rather than improving their archery or doing something ‘useful’. And religions have often had bans on games because of their relationship to gambling,” he says. “Today in the [first] world the norm is to have roles and duties — as an employee, as a parent—while caring for oneself and one’s dependents. And play doesn’t fit into that. It’s seen as trivial in a culture in which everything is measured in terms of productivity. Even sleep and fitness are about improving your ability to fulfil your social role, while sport is considered to have the necessary function of being a community ritual.”

Historically some games got what Detarding calls a “free pass”: early board games—the likes of Snakes and Ladders—were morality tales dressed up as games, while chess or backgammon were associated with a kind of brain-training. Even when play is discussed today there is, he says, often some vague kind of attempt to legitimise it—it’s a way of getting the family together, or it’s for the improvement of one’s well-being, “even that the PlayStation you just bought was in the sale,” he laughs. “But attitudes to play are changing—there’s more institutional approval, for example, with big museums running exhibitions on video-gaming; there’s more questioning of the values we’re expected to subscribe to. There’s also been a lot of boredom over recent years”.

“In one sense play is on the up, especially coming out of the pandemic. People had a lot of time on their hands that previously they hadn’t, and turned to play as something to do, even as a way of dealing with the situation,” says Jeremy Saucier, assistant vice president at The Strong National Museum of Play in New York and editor of the American Journal of Play. “Sure, play has long been associated with childhood—play is ‘what kids do’—even as many adults became more open to it, and even if they might not have called it ‘play’. Yet there’s still a certain risk in revealing that you ‘play’ in modern culture. Play is still considered to be frivolous in a highly competitive world”.

Unless, of course, that highly competitive world co-opts play in the pursuit of improved efficiency in business or consumer engagement with a product: the so-called ‘gamification’ of the workplace and education, in training and marketing. This reveals a philosophical conundrum. “Play has so many possibilities and there are ways to harness it to bring all sorts of benefits. But if you assign a purpose to play, is it still really play?” asks Saucier. “The danger is to recognise that play is good for us and then trying to throw play into everything. Then it just becomes performative”.

Remarkably, even play among children is under attack. Ana Fabrega, founder of Synthesis—an educational system based on the idea that children are hard-wired to learn skills the likes of collaboration, autonomy and competence through play—was a career teacher with experience in school systems around the world. She notes how with the notable exception of the education system in Finland, time for free, unstructured play has increasingly been squeezed out of school timetables in favour of academic study and the pursuit of higher grades.

It’s not just in schools either. “We’re seeing the rise of a culture of safetyism in which parents don’t want to expose their children to even the slightest risk, even though the instinct to explore risk [through dicing with heights, speed, dangerous tools or elements, and so on] is fundamental to children from a very young age,” she says. “Play is being trained out of us, so it’s no wonder that by the time we leave education, we tend to think of it as not being serious. But we have to take play seriously—it matters, not least because it’s the engine of invention”.

According to Peter Gray, the last 50 years or so have seen other cultural influences gradually erode children’s access to free play too, notably the rise of TV and, more recently, gaming devices keeping children within the domestic sphere rather than being “free range” and out in the world. In parallel, this period has seen a huge rise in all sorts of mental disorders among young people.

“The whole reason why childhood is so long is to acquire the characteristics necessary to be an adult. You’re gradually given more and more freedom and so must learn to solve your own problems—how to keep your playmates happy, how to deal with differences,” says Gray. “Now we have generations who have grown up without that [training] and absolutely it’s had a [negative] impact on them”.

In 1955 the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, in his book Homo Ludens (playful man) proposed that human culture arises and advances through play; that the pillars of culture, from art to literature, philosophy to the law, arise at times when adults had the freedom and time to play. It’s through play that we innovate. That might not bode so well for a globalised world in the 21st century.

Indeed, Gray says there is evidence to suggest that the good mood fostered by play allows people to perform better at the kind of problem-solving that requires novel thinking. And that, since the 1980s, curtailed childhood play has had a marked negative impact on creativity, as far as it can be measured. “Play teaches creativity, so now we’re producing far fewer creative people in an era when society really needs people to be creative,” he argues. But, he adds, we’re also seeing it reflected starkly in what he notes as the reduced independence and competence of current late teens and 20-somethings. He worries that this will likely become the norm for future generations unless the greater free rein to play, which was historically given to children, is rapidly reinstated.

“We’re seeing high rates of emotional breakdown among college students, for example, often for what would have been considered very trivial reasons a generation ago,” he observes. “Lacking the beneficial childhood experience of play, they haven’t learnt to steel themselves [against challenges], to understand that you can have a negative experience and somehow you survive. There’s an inability to accept negative consequences and to take responsibility for their own failures. Our changing regard for the importance of play [in childhood] is behind all of this”.

That also suggests why we need to take a more positive view of play more broadly, not just for tomorrow’s children and the adults they will become, but for adults today. Rene Proyer notes that the huge popularity of smartphone- and console-based video gaming—an industry that has long since eclipsed the film business, for example—suggests that the desire is there. The average age of a gamer now? 33, with players equally split between men and women. We just need to be more open about embracing the benefits of play—and to recognise that playfulness as a state of mind is a skill that can be developed.

“For a long time, it was thought that video games were just for kids. Back in the ’80s I was almost embarrassed to tell other grown-ups what I did for a living,” says David Mullich, the leading video-game designer for the likes of Disney, Apple and Activision. “Now everyone is slowly discovering how essential play is. It’s in play that we cast off our responsibilities, fears and certainties to engage in challenges that have no material outcome. It’s through play that we find catharsis. We find new meanings in the world. Without play, we wouldn’t be fully human.”

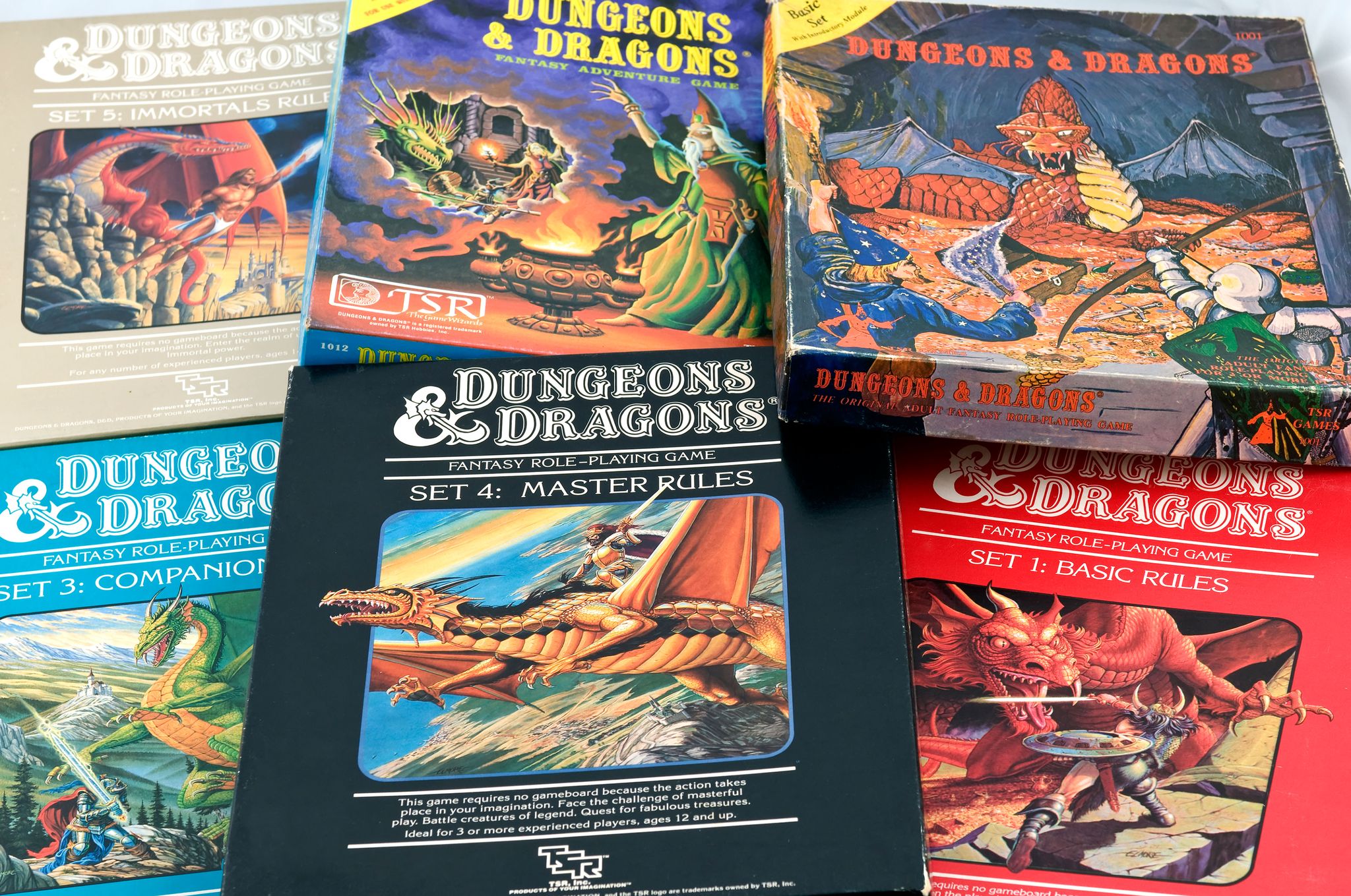

Dungeons & Dragons, the tabletop fantasy roleplay game developed by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in the American Midwest in the 1970s, is about to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Its popularity has been a slow burn. There was an initial boom, then a blip during the so-called Satanic Panic of the mid-1980s, when D&D, alongside horror movies and heavy-metal records and everything else beloved of teenage boys, was accused of being a precursor to ritualistic murder. But now it’s bigger than ever. (Spookily, or not, the Satanic Panic was itself a precursor — to QAnon. Coincidence?? Wake up, sheeple!)

Sales in D&D paraphernalia — the players’ handbook, starter sets, merch — increased by 30 per cent in 2020, but the game was on the rise already, popularised by Stranger Things, Netflix’s hit show. After series four aired last year, Google searches for “how to play Dungeons and Dragons” rose by 600 per cent. Next week sees the release of Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, the first official live-action movie, starring Chris Pine. You know, that well-known nerd.

Sadly, none of which, not even Captain Kirk himself, will do anything to lessen the stigma attached to D&D. I should know. I have been a devotee for a few years now, and no matter how progressive society claims to be, no matter how many series of Stranger Things arrive, people will always snigger when I tell them I play. They look at me as if I’ve said I’m marrying a cow. But they don’t understand the pure joy of it. The creativity, the brotherhood, the feeling of fulfilment when you finally vanquish the necromancer.

It was a slow burn for me, too. As a younger man I was aware of D&D, but only in the abstract. Like Texan barbecue or oom-pah music, it was something I knew other people were into, but not anyone I was likely to encounter. Then, a few years ago, an old friend, Jack, told me he had been “running campaigns” (playing D&D) since university, so I asked if I could join his next game. I couldn’t — it doesn’t really work like that, but Jack offered to “DM” (Dungeon Master) a new campaign (game) for me and some of our friends. A few weeks later, our inaugural quest began over crisps and Kronenbourg in his south London kitchen.

Like all good games, Dungeons & Dragons is both simple and rich in nuance. To get the most from it, you need to be dedicated, attentive and perhaps very slightly stoned. Each player has a character which has either been assigned to them or which they have created. It could be an orc with an insatiable bloodlust, or a hoary old wizard, freshly divorced and out on the pull. You could even be a mewling sous-chef, armed only with a ladle, the ability to shower enemies with cooking grease and a need to make your estranged daughter proud: meet “Malcolm Lightfoot”, a character created by my friend Tom, a TV executive in his mid-thirties.

Some characters are fighters, others are thinkers. Some are at one with nature, able to command woodland creatures to their bidding, while others can raze whole forests with the swing of an axe. There are races, classes, attributes, skills, incantations, evocations, Faustian matriculations… Everything you do is down to chance, and every action has a reaction. Essentially, you can do anything, so long as the DM allows you to try and luck is on your side. That luck is tested by the roll of one of seven dice, ranging from four- to 20-sided. Crucially, you can die. If your “hit points” (life) diminish below the requisite level, then you’re out. End of story.

The thrust of the game is the quest, and the DM is its omniscient architect. He or she designs the loose storyline (generally a mission to retrieve, save or discover something), the world in which the story happens and the obstacles met along the way. The DM also plays all the NPCs (non-player characters). King of the nerds? Truly. But that’s what you want: someone deep in the culture who relishes the quest and takes it completely seriously, no matter the ick. And there can be an ick, especially early on. When someone speaks in their character’s voice, for example, it stings cynical ears. But therein lies the magic. If you can get over that cringe, then you are free. You’ve been red-pilled. But instead of waking up next to Larry Fishburne in a burned-out hellscape, you just pretend to be an elf and laugh uncontrollably.

That first campaign lasted well over a year, with the four of us meeting in that kitchen once every couple of weeks. The only real requirement was to be as dumb and funny as possible, and the quest would sort itself out. It was joyous. Not just for the sheer puerile idiocy of it, but because four grown men were able to relish in play in its purest sense. Like we were six years old again.

In the winter lockdowns, I found solace in weekly D&D sessions via Zoom. My day job was, as it remains, to cover fashion and luxury for this magazine. My other hobbies matched those of many other standard-issue thirty-something men, during those days: I ran more; I baked; I rewatched The Wire and tended a meagre garden. But on Wednesdays I would cocoon myself in the back bedroom, arrange my dice and notepad and settle in for a couple of hours of Tolkienian escapism. Nothing beat the ennui of a looming real-world annihilation like a tussle with a gnome.

Our lockdown crew was stringent in the observance of the rules, which only made the campaigns more fulfilling. The interchanging DMs spent hours drawing maps, creating multifaceted NPCs and writing stirring speeches. Our sessions were chapters, rather than get-togethers, and each time we finished there was a feeling of genuine achievement for each of us — four fairly disparate men, linked only by Zoom and a love of Odyssean storylines.

We tore through the campaigns, and as we went along, my characters became much more complex. When they died, as they often did, I felt the loss keenly. Hjelme, a thuggish dragonborn (humanoid dragon, impervious to fire damage) with a chequered past, sacrificed herself to save another member of the team. In the grip of a pandemic, it’s deeply sad when something you’ve channelled the last of your dwindling creativity into gets mauled by goblins.

Having said that, I was recently ousted from my usual gang on the grounds of perceived low attendance. Invited back only as an occasional cameo. Too much time at fashion shows, perhaps. So I am now at something of a loose end. If you hear of any maidens needing rescue from a curse, you know where to find me. And to those who pour scorn, “na’ga rahn fenedhis!”

Originally published on Esquire UK

See where The Super Mario Bros Movie stands in the long and complicated history of video game adaptations.

If you were a big-ticket Hollywood screenwriter, one of the toughest gigs you could get is the task of turning a video game into a coherent movie. Usually, video game stories are meant to be played and interacted with—not just consumed. It’s why running and jumping as Mario feels amazing... but hearing him talk in full sentences with Chris Pratt’s voice is unnerving.

Most games also tend to run about 30 to 60 hours long—if you don’t get addicted—and reducing all that to a tight 90 minutes is a nearly impossible task. Video games are also inherently ridiculous. You upgrade stats, collect coins, complete quests, and play out an experience unique to what you make of it. It’s something a fixed medium like film can’t even seem to get something simple like Sonic the Hedgehog right. Remember some of his adorable and cool friends like Tails and Knuckles? Well, they don’t even show up until the sequel.

But perhaps most daunting? People love their video games. The characters, the storylines, the visuals: they're all subject to insane scrutiny because you invest your time and energy and 3am. bags of Doritos to be part of these worlds. Now, we have a new adaptation to put under the microscope: The Super Mario Bros Movie. Read on to see where it stands in the long and complicated history of video game adaptations.

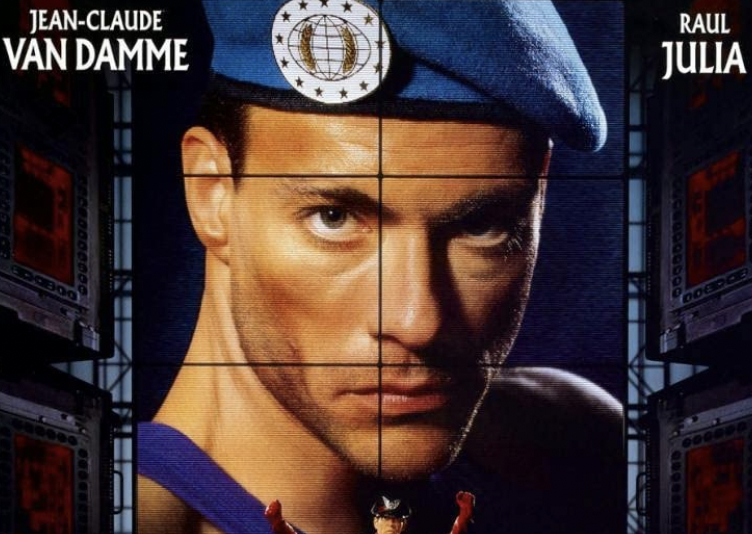

Jean-Claude Van Damme is one of the best action stars Hollywood has even seen, so it was only logical that a guy who starred in dozens of Die Hard clones would eventually get to work with the film’s scribe himself, Stephen E de Souza, on an adaptation of Street Fighter. Outlandish and full of impressive fighting choreography, the '90s film made for an incredibly campy rework of the 2-D arcade fighter. Especially since it (awkwardly) favored the one American character as its lead over its Japanese protagonist. Still, Van Damme can sure kick ass.

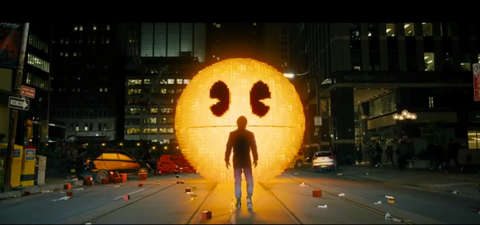

Bet you didn't think Pixels would be on here, huh? 2015 probably told you to hate anything and everything Adam Sandler. Well, it's 2021 and we like the Sandman again. Pixels is a loving, if... uneven ode to the arcade classics of the '80s (think: Pac-Man and Centipede). Plus, it stars Brian Cox and Peter Dinklage. And Michelle Monaghan. Yeah. Pixels deserves a replay.

Uncharted had so much going for it. A genuine star in Tom Holland, who plays the leading adventurer, Nathan Drake. Mark Wahlberg as his co-star. Plus, an apt director in Ruben Fleischer, whose breakout film, Zombieland, is still massively rewatchable. We hate to report that Uncharted is half of what it could've been. Which means that there are still some quips, gargantuan action setpieces, and various acts of Tom Hollanding would seeing. It's just all wrapped up in a film with scattershot pacing and not much character development for its lead.

The creative team behind the Assassin's Creed film took the correct approach. Ubisoft, the game studio, decided to snag the creative reins of the project itself and attach a reliable talent who believed in the potential of the franchise. This talent, of course, was budding Hollywood leading man Michael Fassbender. What he did with the film may not have been exactly a box office pleaser, but it was an example of a video game movie that was done artfully, made with a deep, meticulous understanding of the game series’ lore.

Say what you will about Paul WS Anderson, but he created a world all his own in the Resident Evil film series. The movies, frustratingly, diverge greatly from the storytelling of the games, but Milla Jovovich has become something of a screen icon thanks to her enduring leading role in them. While they take a lot of liberties with the Resident Evil franchise, the world-building in the films is captivating enough to make these a stand-out in the genre.

World of Warcraft is one of the most beloved video game series of all time. Its fan base is large, spanning generations of kids who, in some cases, have been playing it for decades. Duncan Jones’ take on the series showed, perhaps for the first time, what happens when a huge fan of a video game is given the keys to a film franchise. Jones is an outspoken WoW-head, and his knowledge of the series was apparent in this film.

We hate to say it, but Sonic the Hedgehog 2 doesn't go quite as fast as its predecessor, losing some of wit and charm from the first outing. That said, Ben Schwartz's gleefully chaotic work as Sonic, with a superb Idris Elba added to the mix as the echidna Knuckles, makes Sonic the Hedgehog 2 firmly one of the better films on this list.

Sure, the Mortal Kombat reboot was never going to reach the bloody, campy heights of its 1995 predecessor. But it's still a treat for gamers who grew up slicing and dicing back when the fighters were merely two-dimensional.

Sure, the Mortal Kombat reboot was never going to reach the bloody, campy heights of its 1995 predecessor. But it's still a treat for gamers who grew up slicing and dicing back when the fighters were merely two-dimensional.

After Angelina Jolie’s lukewarm take on the franchise in the early 2000s, it seemed like Tomb Raider would never achieve its full potential onscreen. The series itself is extremely cinematic, and, aside from the burdensome exploitation and sexism in the games, it offers what could be a very strong woman-led Indiana Jones-type movie series. In 2018, Alicia Vikander starred in this much darker—and much more realistic—version of Tomb Raider, and she really nailed it.

After Angelina Jolie’s lukewarm take on the franchise in the early 2000s, it seemed like Tomb Raider would never achieve its full potential onscreen. The series itself is extremely cinematic, and, aside from the burdensome exploitation and sexism in the games, it offers what could be a very strong woman-led Indiana Jones-type movie series. In 2018, Alicia Vikander starred in this much darker—and much more realistic—version of Tomb Raider, and she really nailed it.

The Super Mario Bros Movie is for kids. For. Kids. Please remember that, as you watch one mister Chris Pratt Mario cheese his way through Mushroom Kingdom. The Super Mario Bros Movie doesn't totally have a plot—does any Mario game ever veer too far from Mario-beats-Bowser, anyway?—so it leans on the hits. Meaning: a Mario Kart scene here, a Super Smash Bros moment there, and cameos that'll delight even the crabbiest of trolls. Just enjoy it, OK? Life's too short to dunk on an animated plumber.

The Super Mario Bros Movie is for kids. For. Kids. Please remember that, as you watch one mister Chris Pratt Mario cheese his way through Mushroom Kingdom. The Super Mario Bros Movie doesn't totally have a plot—does any Mario game ever veer too far from Mario-beats-Bowser, anyway?—so it leans on the hits. Meaning: a Mario Kart scene here, a Super Smash Bros moment there, and cameos that'll delight even the crabbiest of trolls. Just enjoy it, OK? Life's too short to dunk on an animated plumber.

Final Fantasy is another major gaming franchise that has a subculture all its own. For decades, fans wondered how their beloved RPG would look onscreen. Advent Children, the only film on this list that’s not live-action, answered that call in 2005. The imaginative and at times fully bonkers take on the beloved Square Enix series used computer-generated 3D graphics instead of real life actors, and it really blurred the line between film and gaming.

Final Fantasy is another major gaming franchise that has a subculture all its own. For decades, fans wondered how their beloved RPG would look onscreen. Advent Children, the only film on this list that’s not live-action, answered that call in 2005. The imaginative and at times fully bonkers take on the beloved Square Enix series used computer-generated 3D graphics instead of real life actors, and it really blurred the line between film and gaming.

Listen, if I could give the top spot to "Speed Me Up"—the song of last summer, this summer, next summer, and the summer after that—I would. But my editor won't let me. Instead, props goes to the movie itself, which proved to be a surprisingly fun outing for the blue guy, despite months of production troubles. For better or worse, we'll probably always remember Sonic the Hedgehog as the last movie we saw in theatres before the pandemic.

Listen, if I could give the top spot to "Speed Me Up"—the song of last summer, this summer, next summer, and the summer after that—I would. But my editor won't let me. Instead, props goes to the movie itself, which proved to be a surprisingly fun outing for the blue guy, despite months of production troubles. For better or worse, we'll probably always remember Sonic the Hedgehog as the last movie we saw in theatres before the pandemic.

OK. Wreck-It Ralph isn't technically a video game movie, in that Wreck-It Ralph doesn't exist as a game IRL. But the film imagines a world where arcade game characters meet up in a digital romper room, leading to a celebration of a film about video games and the bad guys that inhabit them. It's weird. It's wild. It has heart. And a Bowser cameo. What else do you need?

OK. Wreck-It Ralph isn't technically a video game movie, in that Wreck-It Ralph doesn't exist as a game IRL. But the film imagines a world where arcade game characters meet up in a digital romper room, leading to a celebration of a film about video games and the bad guys that inhabit them. It's weird. It's wild. It has heart. And a Bowser cameo. What else do you need?

Pokémon as a franchise has always been a stalwart: there are the cards and the TV series and the animated films. Oh, and then there's the game itself, which has defined an entire generation. Even with all that, when Detective Pikachu was announced, there was some (rightful) skepticism about what a live-action film starring the beloved creatures might look like. Not only did the visuals deliver, but Ryan Reynolds and Justice Smith make the outing a blast to watch. Pokémon Go stream it now.

Pokémon as a franchise has always been a stalwart: there are the cards and the TV series and the animated films. Oh, and then there's the game itself, which has defined an entire generation. Even with all that, when Detective Pikachu was announced, there was some (rightful) skepticism about what a live-action film starring the beloved creatures might look like. Not only did the visuals deliver, but Ryan Reynolds and Justice Smith make the outing a blast to watch. Pokémon Go stream it now.

What is there to say about the Mortal Kombat movie that hasn’t already been said? It’s campy. It’s exciting. It’s dumb. It’s brilliant. The spirit of the '90s is alive in full force in this film, and to this day, the techno-futuristic-cage-match title still stands as the most satisfying video game movie to date. Sure, it may not be the most “high-art” example on this list. But Mortal Kombat perfectly captured the essence of a game franchise, and it cannot be beat.

What is there to say about the Mortal Kombat movie that hasn’t already been said? It’s campy. It’s exciting. It’s dumb. It’s brilliant. The spirit of the '90s is alive in full force in this film, and to this day, the techno-futuristic-cage-match title still stands as the most satisfying video game movie to date. Sure, it may not be the most “high-art” example on this list. But Mortal Kombat perfectly captured the essence of a game franchise, and it cannot be beat.