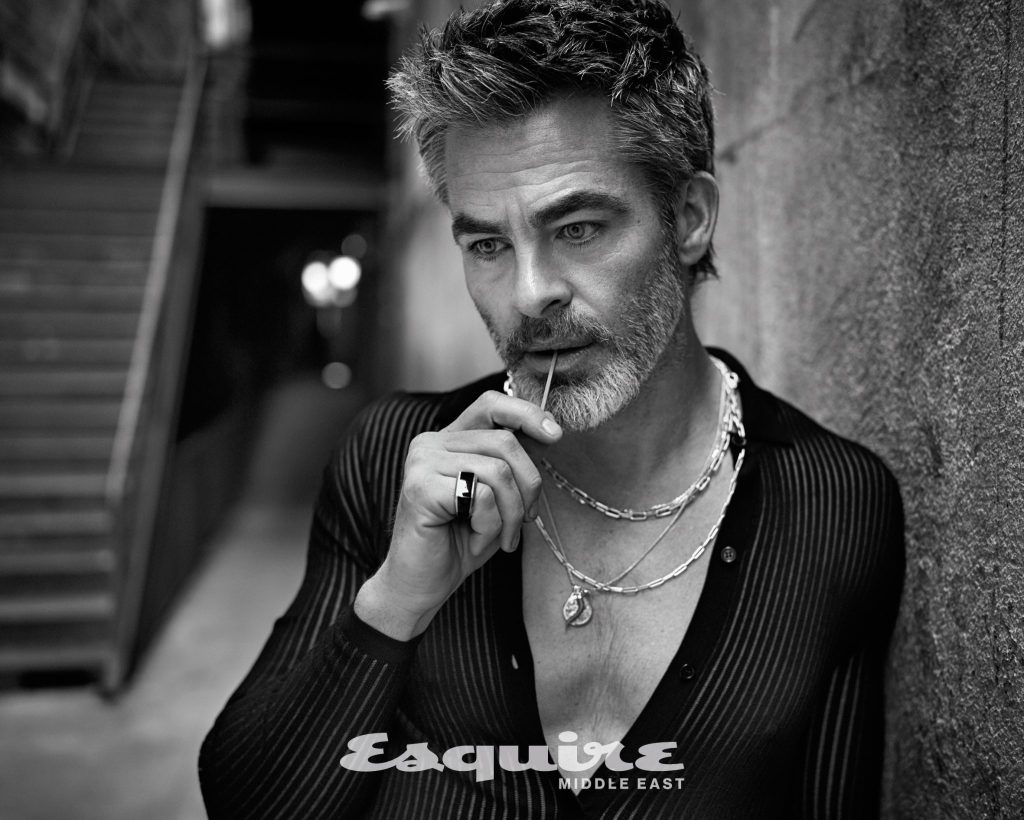

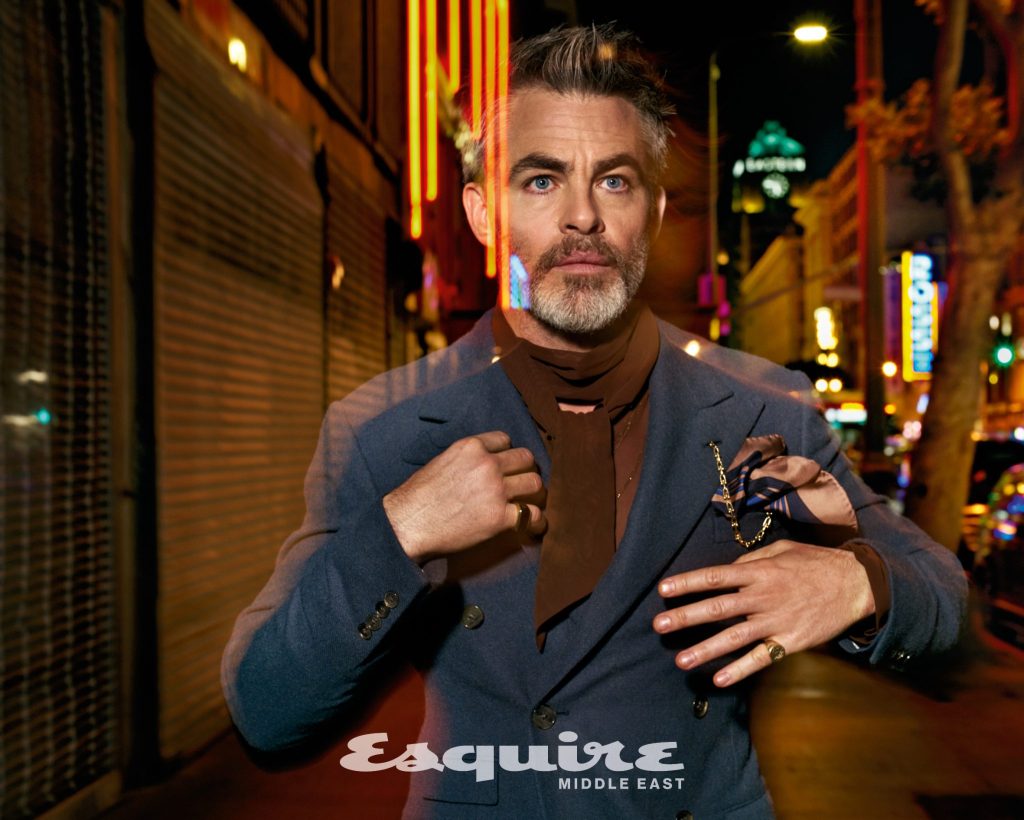

Hollywood tried to turn him into a heartthrob, the handsomest of the Chrises. But while everyone was taking him for granted as the likable dude with the thousand-watt smile in franchise fare, Chris Pine was figuring out just what kind of actor—and man—he really wanted to be. Twenty years into his career, at his home, high up in the hills of Los Angeles, he ponders the next twenty.

“Okay—cedarwood,” Chris Pine says. “Here we go. Rosemary.”

Monday morning in the hills above Hollywood. We’re in Pine’s sauna, a cube of wood and glass near the edge of his property. Pine—lightly bearded, shock of graying hair, wearing only orange board shorts—is perusing little bottles, dripping essential oils into a waist-high chimney topped with hissing hot stones, fine-tuning the vibe.

“Oh, yeah. Enoki leaf,” he says. “We’ll do that.”

Pine flicks the thermometer: 120 degrees and rising. He picks up a bundle of leafy twigs—to move the air around, he explains, not the kind you whip yourself with, though he’s got one of those, too. He moves the air around. Then he climbs onto the bench next to me and folds himself into an impressively deep yoga squat, ass down by his heels.

The air in my mouth feels like cotton candy. I reach for the insulated water bottle I’ve been provided. “If you taste something in that,” Pine says, “I put a bit of barley tea in there.” He tried it at a Korean restaurant; now he’s into barley tea. It’s become part of the overall sauna process.

Pine enjoys a process. Making an espresso, building a fire. “I love any sort of ritual,” he says. “I can even get into a Catholic Mass becauseI like the aesthetic. And a sauna is a whole ritual. It’s about gifting yourself a period where there’s nothing to do other than to purify, to release, to cleanse, to start again.”

We’ll sweat and release and cleanse here for twenty minutes, until the heat becomes intolerable, then we’ll hit the unheated outdoor pool—just in and out, a quick car-battery shock to the central nervous system—and finish strong with a dip in the cold plunge, a barrel of what feels like near-freezing water built into the ground. This is how Pine, forty-two, does it every day, except we’re doing it in the morning, and he prefers to do it in the afternoon, sweating out the day’s physical and psychic accumulations. Being out in the world makes him “kind of emotionally and physically tired, so I need some sleep and some sauna time, and reading, and just puttering about in the garden.”

When he’s alone in the sauna, Pine will stretch or listen to a podcast, but because I’m here, we talk about his last big moment out in the world: the seemingly quite nutso Don’t Worry Darling press tour, consumed soap-operatically by a diversion-craving populace when the film premiered in Venice last September. “If there was drama, there was drama,” Pine says of the shoot, but for the record, “I absolutely didn’t know about it, nor really would I have cared.

If I feel badly, it’s because the vitriol that the movie got was absolutely out of proportion with what was onscreen. Venice was normal things getting swept up in a narrative that people wanted to make, compounded by the metastasizing that can happen in the Twittersphere. It was ridiculous.”

He speaks well of Olivia Wilde and Harry Styles (“a sweet guy”), loves Florence Pugh—whom he first worked with in 2018’s Outlaw King—“to f***ing death,” and maintains that nobody spat on anybody in Venice.

And those photos of Pine spacing out during that Venice press conference, the ones people turned into memes imagining him rethinking his every life choice, trying to astral-project his consciousness away from the torture chamber of the Darling promo cycle? “All the memes I saw about my face in Venice made me f***ing laugh,” he says, especially the one captioned “me on an important Zoom call watching my cat throw up on the sofa.” But he swears all he was doing was admiring the ceiling of the Palazzo del Casinò, jet-laggedly. “Sometimes the question’s not that interesting and you just f***ing zone out, and you’re looking at a ceiling because it’s really pretty.”

The runaway narrative around Darling meant nobody talked about Pine’s magnetically unpleasant turn as a mid-century-modern cult leader, recasting his natural charisma as something toxic and threatening for a movie about retrogressive masculinity. It’s the latest of many Chris Pine films in which he simultaneously embodies and interrogates an old-school idea of movie manliness, squaring the past with the values of the present. It starts with his James T. Kirk in 2009’s Star Trek—just enough sixties Shatner swagger, shaded with vulnerability and even irony. You can see it most clearly in his two Wonder Woman movies, particularly the wacky, misunderstood Wonder Woman 1984. Here Pine turns Steve Trevor—easily among comicdom’s top five blandest white guys—into a real character, supportive and self-sacrificing and secure enough in his masculinity to fall for an Amazon who can break him in half.

Pine is always down to step outside the franchise-hero zone entirely, game to go dark (as in Hell or High Water, probably the best movie he’s made, in which he’s a perfect noir protagonist, sweaty and hounded, slipping through police roadblocks with a duct-taped gunshot wound) or defy augury entirely (singing a medley of “I’ll Be Seeing You” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” with Barbra Streisand on a duets album). Some directors have noticed this and cast him accordingly; Patty Jenkins wanted him for Wonder Woman after seeing him play Cinderella’s Prince in Into the Woods. Mostly, though, he still gets offered scripts that call for a Chris Pine type as defined by Captain Kirk, Jack Ryan, and the rest. An old idea of Chris Pine.

“The material that interests me is not always the kind of material that’s offered to me,” he says. “And I can only do so much in terms of reaching out to writers and directors I like, or telling my representatives what I want to do.”

This month, Pine is in another big-budget movie (the seemingly very franchisable Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, in which he’s as charming as he’s ever been onscreen, and maybe more relaxed), but he’s also preparing to roll the dice with a personal project that could change the course of his career. Or it could not.

“We’re in a business of perception, and I’m reminded often that the way that I know and experience myself and perceive myself is oftentimes wholly different than how the industry does, or artists and creators that I’m interested in working with,” he says. “They think my interestingness only goes so far, I guess.”

We exit the sauna, plunge, curse, grab robes, and head for the main house to dry off. Pine bought it in 2010 for a reported $3.1 million, which paid for about twenty-two hundred square feet of actual house and 1.5 acres of priceless post–Star Trek privacy. Aside from the high white wall of Griffith Observatory in the distance, you can’t see anybody else’s house from the property. Somewhere on Pine’s acres, he’s got four rows of wine grapes growing, and he makes sure I go home with a bottle of Fine Pine Wine “Ms. Sauvy B” 2021.

I’m here to ask Chris Pine questions about Chris Pine, but as we’re crossing the lawn to the front door, there’s something Chris Pine wants me to tell him. “I’m a pretty intense question asker,” he’s already warned me, and this turns out to be true. By the time I leave Pine’s place, I will have told him why I wrote my first book, why I dropped out of college, what my one tattoo means, and where I was on 9/11. Ben Foster, who’s made three films with Pine, including Hell or High Water, calls him “one of the most interested people I’ve ever met.”

What Pine wants to know about me now is if I liked Dungeons & Dragons, because when we meet I’m one of the few civilians who’ve seen it. When I say I liked it, he asks, “Scale of one to ten—how much did you like it?” I tell him I’d give it an eight, which Pine seems okay with. It’s probably more of a nine—genuinely funny in ways you don’t necessarily expect from an action flick based on a role-playing game—but I don’t want Pine to think I’m kissing his ass.

I played a lot of D&D as a kid. It’s a game with a rich mythology and ten million persnickety little rules; the most fun part of playing it is sitting around a table with your friends making dumb jokes about what’s happening, and Honor Among Thieves is the first screen adaptation of D&D to capture that. After ten-plus years of Game of Thrones setting a bleak life-doth-suck tone for all heroic-fantasy storytelling, comedy was the only direction to take this material, but cowriter-directors Jonathan Goldstein and John Francis Daley strike a delicate balance, eschewing solemnity while avoiding that overly knowing style in which all the characters talk like they’re pitching jokes in a TV writers’ room.

Pine plays Edgin, a lute-plucking rogue who assembles a misfit crew to recover his young daughter and a dangerous magical artifact froma former associate who’s absconded with both. Pine has been funny in movies before, but this is the first time one of his films has depended this much on his comic timing. “Until we actually worked with him, we didn’t realize how funny he was,” Daley tells me.

“When you’re that good-looking—I think a lot of actors have a discomfort level with letting themselves be the source of amusement for people at their expense,” Goldstein says.

“But not Chris.”

“He embraces any moment where his character is emasculated,” Daley adds.

Daley and Goldstein have said as much to their star. “They’re like, ‘We’re just so thankful that you’re willing to emasculate yourself onscreen,’ ” Pine says, laughing. “I was like, ‘Guys, this is not the way to go about complimenting me.’ ” But he gets what they’re saying. He enjoys being the comic relief, letting other actors have the slo-mo badass moments. It’s why he loved the goofy eighties-fashion-Ken-doll makeover montage in the second Wonder Woman: “I’m willfully emasculating myself, because I just don’t give a s**t. If it makes me laugh, it makes me laugh.

I love looking like a fool.

“Kirk’s like that, too,” Pine points out.

“In [Star Trek], he’s James Dean, and then he walks in to meet Bones and he hits his head. I want to be able to show that you can be cool and masculine without having it be a pissing contest all the time. And if you’re pissing, sometimes you piss on your foot and you can look like a f***ing idiot.”

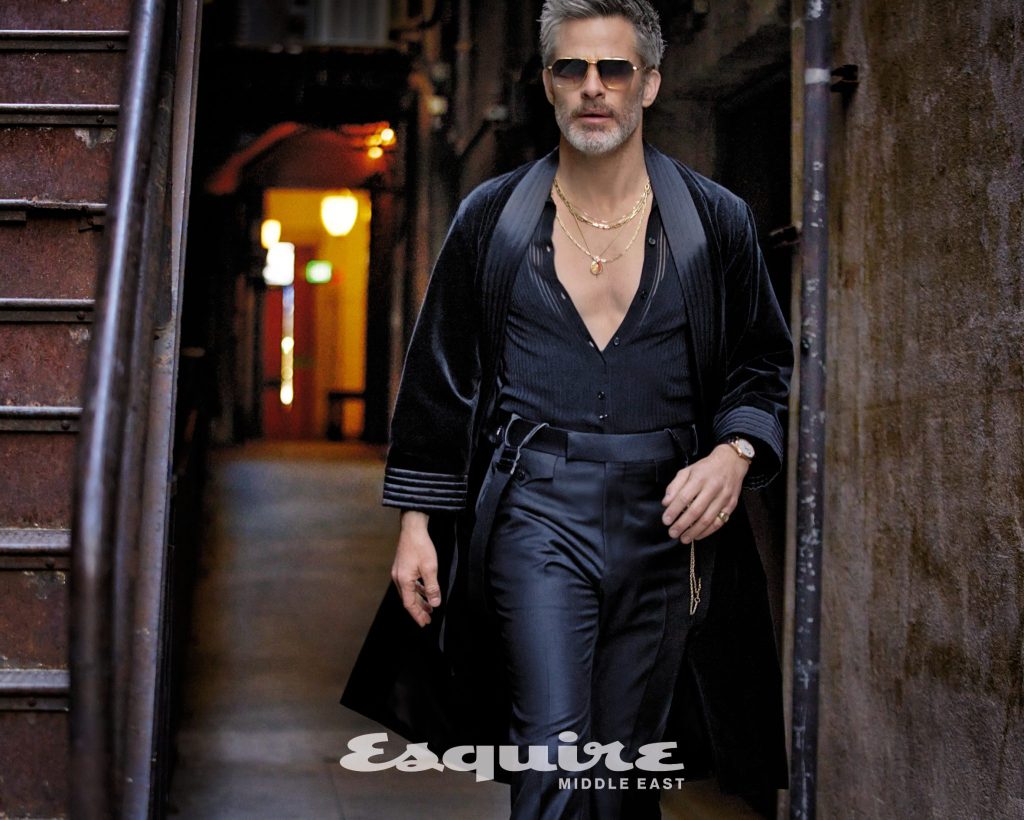

Last spring, Pine let his beard grow out—way out—for a movie, then kept it for a while. He was publicly bearded at a bunch of red-carpet events, usually wearing something blousy and open-necked, sometimes with a gold medallion. If Carly Simon had not written that line about “walking into a party like you’re walking onto a yacht” for whomever she wrote “You’re So Vain” about, she could have written it about Chris Pine at parties circa March 2022. He looked like a horny European art dealer on his way to meet Mick and Bianca at Studio 54. He looked like the man partying makes you think you are.

“That guy,” Pine says as I scroll through a few images of his beardo phase on my iPhone.

“Gregg Allman meets someone that just came from a Bob Evans late-night slumber party” is how he describes the look. “I was definitely feeling myself there.”

The inside of Pine’s house—where we’re warming up by the fire, two guys in robes on contour chairs—has a similarly retro appeal.

No television visible, old books on the shelf, old Life magazines on the coffee table, old records—Sonny Rollins, Tim Hardin, Roxy Music—in a bin by the tube amplifier. Geometric slashes of paint fill the spaces between the framed photos and paintings on the walls, bringing to mind a Dragnet set decorator’s idea of a hippie crash pad, but the overall vibe is Serenity Now. You could really hole up alone and grow a beard in a place like this. “Before the pandemic,” Pine says, “and definitely in my thirties, when I was partying a lot, I would have some epic parties up here, and a lot of guests.” Post-Covid, though, “it’s been a pretty solitary, monastic existence up here.”

The most modern-looking objects in the room are a couple Captain Kirk Funko Pop figures positioned discreetly on a low shelf. You get two distinct feelings when you talk to Pine about

Star Trek—the sense that he still feels real affection for his Starfleet crewmates and real humble gratitude for the experience, and also the sense that, in Pine’s life, the franchise is a massive machine, like the Enterprise itself, that came around once and beamed him up and made him part of something bigger than himself, something that felt almost impossible to live up to in the moment, and then deposited him back into his working life with different prospects and different concerns, and that in the years since he last played the part, in Star Trek Beyond, he’d maybe come to a peaceful place in terms of letting Kirk go.

Pine’s first Star Trek came out a year after the first Iron Man; Beyond was released in 2016, after Marvel’s interlocking mega-franchises had moved the goalposts for what constitutes a hit. Beyond’s gross—nearly $344 million globally—was good money, but not ‘Avengers good’. “I’m not sureStar Trek was ever built to do that kind of business,” Pine says.

“I always thought, Why aren’t we just appealing to this really rabid fan group and making the movie for a good price and going on our merry way, instead of trying to compete with the Marvels of the world?” He’d like to span more years as Kirk but wouldn’t be surprised if Beyond was the end of it. “After the last one came out and didn’t do the $1 billion that everybody wanted it to do, and then Anton”—Yelchin, who played Chekov—“passed away, I don’t know, it just seemed . . .” He pauses, looks out the window at the view Star Trek bought.

He doesn’t finish the thought but a few minutes later suggests that the franchise “feels like it’s cursed”—it shouldn’t be this hard to figure out how to do another Star Trek movie, yet it’s taken six years. Pine and crew’s return to the screen was announced in February 2022; when I speak to producer J. J. Abrams by phone, the search for a director is ongoing. Abrams is elliptical about the film, even by J. J. Abrams standards.

“I will say it’s the first time [since the original reboot] that we have a story that feels as compelling as the first one.”

Even this is news to Pine. “I don’t know anything,” he says. Which is apparently pretty standard: “In Star Trek land, the actors are usually the last people to find out anything. I know costume designers that have read scripts before the actors.” Is it weird, I ask, to be the captain and know so little about what you’re signing on to?

“I would say it’s frustrating,” Pine says. “It doesn’t really foster the greatest sense of partnership, but it’s how it’s always been. I love the character. I love the people. I love the franchise. But to try to change the system in which things are created—I just can’t do it. I don’t have the energy.”

I duck into the bathroom, change out of my swim trunks. On the bathroom wall above a big stone Buddha there’s a framed copy of the January 1942 issue of Hollywood magazine, with the actress Anne Gwynne on the cover in Dale Evans cowgirl regalia. Next to that there’s an action figure framed in its original packaging, complete with Toys “R” Us price tag—Sarge, from the seventies motorcycle-cop series CHiPs.

Anne Gwynne, who in 1942 could be seen alongside Abbott and Costello in Ride ’Em Cowboy, was Pine’s maternal grandmother.

And the actor who played Sarge is Pine’s father, Robert Pine, whose career stretches from the last days of the old studio system to the age of streaming—he entered the business as a Universal contract player in the mid-sixties and showed up most recently in last year’s Apple TV+ miniseries Five Days at Memorial. But CHiPs is still his best-known credit—six seasons, 139 episodes, countless laughing freeze-frame endings.

Chris Pine was born in 1980, midway through that run. Lived in Studio City and Valley Village, went to the Oakwood School with Henry Winkler’s daughter. Actors never seemed magical to Pine; acting was a job. “I didn’t give a f**k what my father was doing,” he says. “All I knew is that sometimes there was work, sometimes there wasn’t, and sometimes money was tight.”

Pine never saw himself becoming any kind of artist. He wanted to play baseball, he says, “until I was thirteen and realized my glaring mediocrity.” After that, he had drive—the ambition to be something, whatever it was—but nowhere to put it. “I just wanted to do well. That’s how I was raised—to succeed. But I didn’t really have any focus.”

Pine clearly doesn’t love the part of the celebrity-profile process where he’s required to tell this portion of the Chris Pine story yet again.

It sounds too easy. Shy kid who never wanted to be an actor starts doing theater in college, tries acting for real, can’t book s**t for two years—“Those two years sucked; they felt interminable”—but by 2003, he’s speaking his first lines on TV. He’s a drunk frat guy on ER, and then he’s on CSI: Miami, wearing a fake lip ring as a cocky skater dude whom Horatio Caine can’t wait to put in jail. That same year, he’s cast as Anne Hathaway’s love interest in The Princess Diaries 2, because at this early stage the one big thing Pine has going for him is that he looks like a Google search result for “handsome prince.” And within five years of that he’s reading for Captain Kirk.

But the quickness of Pine’s rise meant Star Trek was where the hard part started. He turned thirty in 2010, the year after it came out. Within a few months he’d be in Tony Scott’s Unstoppable, trying to stop a freight train while staring down the freight train that is Denzel Washington. (Quentin Tarantino would later say it was Unstoppable that made Pine his favourite Hollywood Chris.)

The movie-star phase of Pine’s career had begun, but he felt lost.

“I would call most of my twenties the blind pursuit of success, doing as much as I could as fast as I could,” he says. “And I burned out. I woke up at thirty, like, What the f**k just happened? I was rich and successful and all the things that ostensibly should be the markers. And I’m like, What is it that I’m doing? And why?

“I was pretty depressed and lonely and really not present,” he continues. On the first Trek, “I was very hard on myself, super perfectionist, this kind of Calvinistic thing: If I’m not feeling pain, I’m not producing.” It was a miserable way to work, he says, and he was “probably miserable to be around.”

It didn’t happen all at once, but as soon as he started to see it, he began reevaluating his priorities. “From about thirty onward, I made this conscious choice to seek joy. Not invest in this ephemeral, intangible perfect,” he says. “And the less I do, the kinder I am, the better and deeper the results.”

Even as an a-list star, you’re ultimately at the mercy of decision-making forces beyond your control. You’re seen a certain way, and it shapes what you’re offered. This is the job.

Which, in a roundabout way, is why Pine spent the past two years making a movie called Poolman, a mystery in which he’s an L. A. apartment- complex pool cleaner turned charmed-idiot gumshoe. When we’re done talking today, Pine will change into jeans and a white T-shirt and drive to a film-production house in Burbank, where he’ll do the final colour-correction pass on the movie,

and by eight or nine o’clock tonight he’ll officially be finished with his directorial debut.

Patty Jenkins remembers the conversations that led to the movie. They were in Spain, shooting Wonder Woman 1984, making each other laugh between shots. “It was the guy’s name, Darren Barrenman, and his job—poolman,” Pine says.

“It just made me giggle.”

But Jenkins also remembers telling Pine around the same time, “You gotta do something else on these tentpoles besides wait in your trailer.”

“She said it felt to her like I was really bored, that maybe I felt uninspired, that I was doing the same old shtick,” Pine says. He believes there was some truth to that.

He met with at least one writer about developing his pool-cleaner idea but ended up writing the script himself, during quarantine, with his long-time friend Ian Gotler. They met every day, talked about the best scripts ever written, screened Chinatown and broke it down. The film they wrote hinges, like Chinatown, on misappropriated L. A. water; unlike Chinatown, there’s a scene in which the characters realize they’re in a Chinatown-type situation and decide to watch Chinatown on VHS. Poolman shares DNA with slacker noirs like The Big Lebowski and Inherent Vice; Darren’s somewhere between the Dude and Chauncey Gardiner from Being There. But the movie is more than the sum of its influences. It has its own rhythms, its own concerns. It never feels like an exercise. As Harry Styles might say, it feels like a movie.

When Pine sent Jenkins the first draft, she was a little shocked. “It was a f***ing masterpiece,” she tells me. “I couldn’t f***ing believe it.” She came on board as a producer. The financing started to flow once Pine signed on to star. And while he says he didn’t conceive the film in order to direct it, after he and Gotler had written it, he “couldn’t imagine it being directed by anyone else.”

Pine cast Danny DeVito as Darren’s neighbour Jack, a down-on-his-luck movie director. DeVito’s own directing career stretches back to Taxi; he says he can tell when a first-time director has the goods. “I used to call him Orson,” DeVito says—as in Welles, as in wunderkind. “Right out of the box. Details. Has his finger in every pie. A very strong vision.”

Annette Bening—who plays Diane, Jack’s wife, an actress who becomes a Jungian analyst—says Pine brought an actor’s instincts to the job.

“He knows how to kind of whisper in your ear, which I think most people prefer. A quiet, intimate exchange.” A quick one, too: “Long, intellectual treatises, once you’re in front of the camera, are never happy experiences.”

Diane and Jack function as surrogate parents to Pine’s Darren. It happens that Pine’s mother, Gwynne Gilford, was an actress who became a marriage and family therapist; in one scene, Jack tells a rambling, pointless story about a restaurant experience where you cook your own food that Pine says is cribbed in part from a similarly rambling story his own father told him during a quarantine-era family visit.

“Jack and Diane are versions of my parents,” Pine confirms. “On its deepest level, this movie is about a boy-man becoming a man, individuating and figuring out who the fuck he is separate from his parents, and coming to terms with the idea that he’s felt alone. There are some bigger life issues I think I was dealing with, making this thing.”

Including—maybe—giving himself permission to make it at all. Jenkins is convinced that Poolman marks the debut of “a big-time, prolific director. This guy is not going to stop. This is so who he is. I think he might be more of a writer-director than he is an actor.”

But when I tell her Pine seems a little self- conscious about presenting himself that way, she’s not surprised. Jenkins points to Pine’s background—to his parents, to a father who did more than four hundred episodes of television, the model of a working actor, blessed over the years with a few steady gigs, never a household name, earning a living one Murder, She Wrote or L. A. Law or Baywatch at a time. “That’s what Chris thought being an actor was,” she suggests. “So it’s uncomfortable to step out of that into being, A, a huge movie star but then, B, going even further, to be a grand artist. There’s something for Chris about being content with the space he’s occupied in his career—I’m a journeyman actor, I’m just happy to be here—that Chris very much can’t stop applying to himself. There’s always a part of him that’s like, I’m lucky to be offered anything.”

Sitting at his dining-room table now, wrapped in a soft southwestern-patterned cardigan, Pine tells me that with Poolman finished he’s thinking about two new projects: a script a friend wrote based on an idea of Pine’s, and a script by somebody else that he read a long time ago. Neither one is far enough along to talk about,

but if either one happens, he wants to direct as well as star. “And I haven’t read anything else, in terms of acting, that’s excited me at all,” he says.

As he approaches these new avenues, is there a voice that says, I should just be happy with what I have? “Oh, yeah. Without a doubt. How I was raised, the dynamic of a household dominated by a worry about whether we’d have enough money—I know on a cellular level how that anxiety affected me and my family. I can’t even believe that I can take a vacation whenever I want. I can go out to eat wherever I want.”

As soon as he says this, I see him thinking about how it’s going to read. He says, “Let me absolutely contextualize this,” and then: “I was always taken care of. I never wanted for anything. I went to private school. But within that was the feeling of financial scarcity. So yes, I think having grown up that way makes me certainly much clearer about what I have and maybe what I need, and that it’s not tied to happiness per se, but I think it’s just tied to calm. I can start paying attention to things that my parents just didn’t have room to think about.” Things like extricating yourself, slowly but surely, from a highly profitable pigeonhole, wanting to be and do more, admitting you want that.

“It’s been mapped onto me since I was twenty- one, twenty-two years old,” he says, regarding that earnest-hero idea. “For a long time, you just embody it, until you’ve been in the business long enough and things start to shift. For a long time, I felt like the clothes were wearing me, but I was a good enough mimic to pull it off. Then you start kind of molding these characters to you, and people start seeing what you’re doing, and maybe even shifting the archetypes to really fit who you are.”

A few weeks after our sauna, I watch Poolman with Pine and Gotler in an otherwise empty screening room on the Paramount lot.

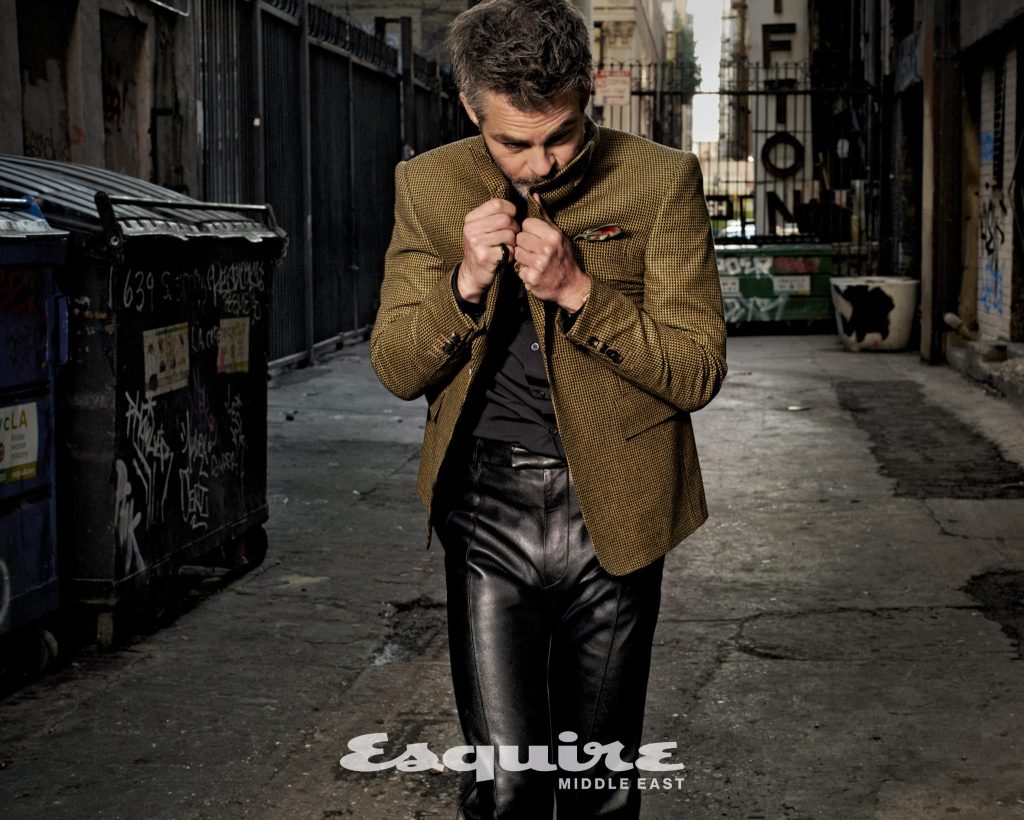

I sit behind them, and here I can tell you what it’s like to watch Pine watch his own movie—laughing with Gotler, bobbing his head to the beat in the pacier scenes, feeling the music of the edit. But what I’ll remember most about that day is what Pine was wearing—another superb ur-seventies getup, full-on double denim, stiff boot-cut vintage jeans and matching jacket plus cowboy boots, as if he rode into town to shoot pool after a long day of squinting at his oil rigs.

He was nailing it. I can think of exactly two other people I’ve seen pull this look off this well. One of them is Brad Pitt. The other is Robert Redford, specifically as an itinerant dirt biker in 1970’s Little Fauss and Big Halsy, an artistic disappointment for Redford but a huge moment for the Canadian tuxedo. I’m not suggesting that Chris Pine decided, while getting dressed to go watch his directorial debut, to deliberately cosplay another great-looking movie star who leveraged his movie-star clout to do a lot of different things, including directing. (Redford did it for the first time when he was forty-three, one year older than Pine is now.) But if you’re Chris Pine and you’ve paid attention over the past twenty years, you must know that half of everything is about looking the part—and how far that can take you if you let it.

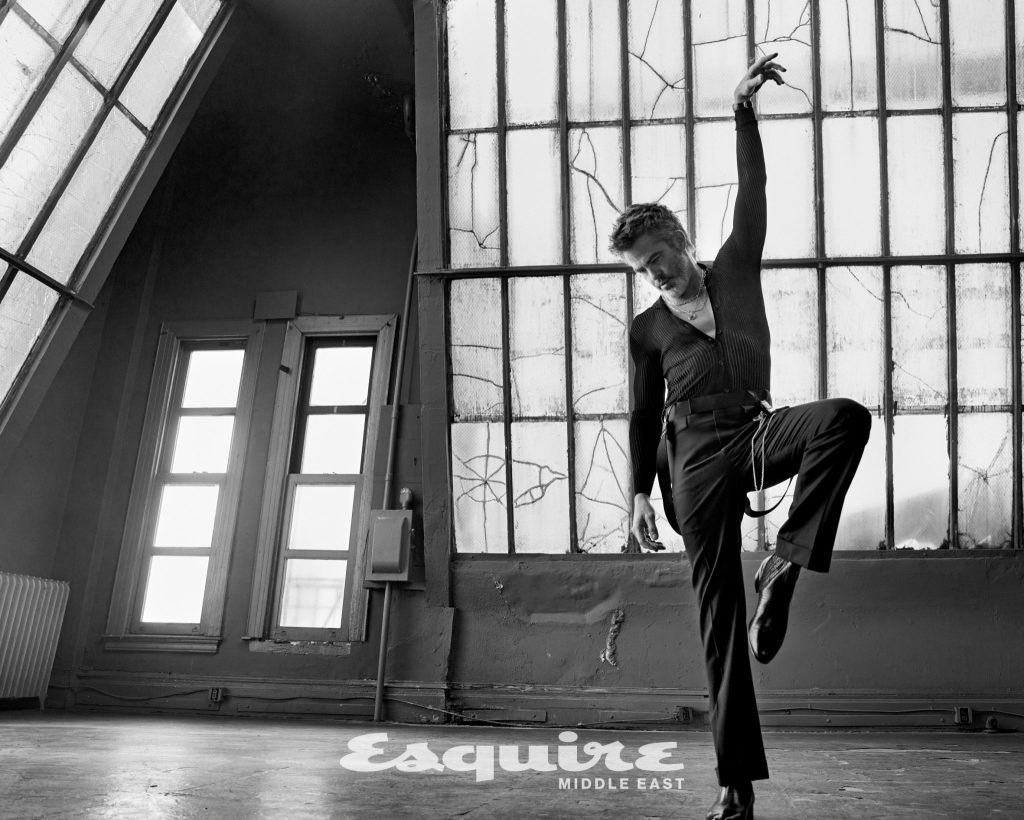

Photography by Mark Seliger

Styling by Colleen Atwood

CASTING BY RANDI PECK / PRODUCTION BY RUTH LEVY AND MADI OVERSTREET

GROOMING BY NATALIA BRUSCHI USING UTSUMI SHEARS AND TOM FORD BEAUTY

TAILORING BY CHRISTINE VLASAK