It’s funny how the roles reverse between child and parent as the years jostle along but that’s kind of how they are now between me and mine. Coming from a small village in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, my mother immigrated to Great Britain in the 1970s in search of a better life. Till then, she had the back-breaking job of selling Hakka-Chinese food along Calcutta’s streets, a position she’d held since the age of six to support her family. Eventually came a golden ticket to relocate, and the SGD12 she’d saved up would kick start a new life. That, in the UK though, was spare change. Mummy would have to hustle much harder.

By the time I was born, my mum was juggling two gruelling jobs. During the day, she worked in a Chinese restaurant and come night she worked in a hospital. She’d sleep on the shop floor before it opened, and somehow still managed to meal prep for two kids before the night shift. To help, I became the model teenager any Asian immigrant could hope for: I got straight As at school, and spent all my spare time helping out at the restaurant—that’s a lot of prawn crackers packaged. We knew nothing of family recreation and I often wondered how my white friends had time to go to theme parks or the beach with their parents.

When I was at university, Mum and I experienced luxury for the first time. We had relatives in town and they booked a table at China Tang, a restaurant in Park Lane’s most famous hotel called The Dorchester. I remember that day so clearly: Mum pulled the labels off her most expensive (high street brand) clothes, we posed for photos in the lobby for what felt like forever and every bite of dim sum was savoured with a squeal. When the bill came our hearts jumped but we talked about that incredible experience for years to come and I vowed one day to take her back to that hotel myself.

My 20s were a blur. You know that time when you’re chasing promotions, are all consumed by first love and going to parties every night because your liver can perform magic tricks? I didn’t visit often while I found my way in the world as an adult. As my 30s entered I was living abroad and Mum visited me in a handful of cities. It was in Tokyo, though, that I noticed she couldn’t quite keep up. I’d walk ahead while she limped behind and climbing the stairs became a challenge. She was in her 70s, and I’d failed to really acknowledge her fragility, mostly because I was in denial. We easily label our parents old, but rarely do we see them as weak. Certainly not my busy-body single mother who can hold down multiple jobs, raise children, and eventually amass a small fortune in real estate. A health scare ensued and I realised I needed to dedicate much more quality time with my mum.

Now, I’d never before considered her to be a travel companion. We have very different tastes. I like outdoor adventure, and she prefers shopping malls; I like experimenting with local food, and she complains when the meals are not Asian, because "if there’s no rice, she’ll be hungry"; and of course, there’s the nagging, which is incessant, to say the least. Still, once a year, I plan an international adventure for us, and admittedly it’s always more fun than I anticipated. We recently journeyed to South Korea, but it’s the cruises we enjoy most because both of us can have our needs met. On a Virgin Voyage around Greece, I could have vegan while she did Korean barbecue, and we checked off multiple islands without the stress of public transit. This summer we’re sailing on a Norwegian Cruise Line to Iceland. It’s the best way for her to see the fjords and the Northern Lights from the comfort of her own balcony.

We’re dining quite fancy once a month too, and it’s about damn time. I see it as a small contribution to making up for a complete absence of indulgence in the first 70+ years of her life. This is someone who scoffed plates down between shifts, and never once took a self-care day. Now, I want her to slow down and enjoy life’s bounty—and of course, I’ll settle the bill. She can’t comprehend the marked-up price of rice in a nice restaurant, despite that being her main stipulation for dining out.

The average person in the world lives till they’re 73 years old (83 in Singapore), so it’s easy to do the math to figure out how many more Lunar celebrations or annual vacations you’ll possibly have with your parents. For most millennials, it isn’t that many at all. My mum turns 80 in 2024, and I know exactly how to mark the special occasion. We’re going to have dim sum at China Tang and she’s going to stay overnight in The Dorchester for the first time. It’s quite a splurge but I’ve been saving. Every year with her is precious and honestly, I wish I’d started doing this much earlier.

I have lived in the same apartment block for more than a decade. Real estate being as it is in this country, especially in the city where I live, everyone here is holding. Not one of the owners has sold in the entire time I’ve been here. We have watched one another grow up, settle down, have kids. The carpets smell like 1976. It is a time capsule in concrete.

A few years ago, my upstairs neighbour died. This is a polite way of saying he dropped dead of a heart attack, out of nowhere, and they still haven’t figured out why. I really loved this neighbour. He had always been so thoughtful and generous with me. He was only a few years past 40.

At his wake—which, for some reason, was vastly more upsetting to me than my own father’s funeral—they played "All My Friends" by LCD Soundsystem. Perhaps for the first time, death no longer felt like an abstract concept. It didn’t just happen to people beyond retirement age; the old, infirm and grey. Someone had died who adored the same music I did. He was older than me, but we were part of the same generation. I had never considered my own mortality before, but now, as LCD frontman James Murphy sang the same refrain over and over, and men cried quietly into their lagers as they stared out at the sea, it was all I could think about.

Culturally, men are less likely than women to ruminate on their own mortality, but we are preternaturally obsessed with the idea of legacy. Some of the most famous men in history (Napoleon, Alexander the Great, 50 Cent) spent much of their lives thinking about what would happen after they died and how they would be remembered, even though, at least from what I can ascertain, they never actually considered how and when they might die. Even regular, everyday men like me retain trace elements of this sort of ego. We talk about ancient, irrelevant ideas like ‘family lines’ and ‘lineage’. We fast-forward to the statues of us erected in public squares, the memorial plaques detailing our achievements, forgetting the bit where we stop breathing.

The very fact that we’re more likely to indulge ourselves in risky, dangerous behaviour shows we seldom entertain the notion of death, at least not seriously. No doubt, this in part influences why we typically die younger than women. It’s not called a "never-say-die" attitude by mistake. Yet I often think about it now. It creeps into my subconscious, mostly during mundane parts of the day, this corporeality. I notice my body more. I consider the very real prospect of its deletion, and that I ultimately have very little control over when or how this happens. I consider how annoying it will be for my next of kin to sell my vinyl collection and my many hardback books.

I suspect this dawning understanding of the finiteness of life is not unrelated to becoming a parent for the first time, in seeing aspects of yourself reborn as a new entity. Major milestones such as this typically correspond with the age at which men draft wills. But I’m less interested in the logistics of one’s life ending than in what it actually means. Though I am (hopefully) nowhere near dying, I find the inevitability of death for all of us fascinating. What will it mean when my first friend dies? Will I die first or will my partner? How will my family and social networks shift and change over time, rendering previously permanent structures impermanent?

Dad would be a good person to talk to about death, except that he never really talked about it. I was too young in any case, barely midway through my twenties when he passed. It was a bulletproof age. I smoked imported cigarettes. I drove recklessly. Took drugs. Had unprotected sex. When you are so pumped full of life, fingertips almost crackling with it, death is the last thing you want to talk about, and your old man is the last person you want to discuss it with.

My father was a GP, which means he wasn’t interfacing with death every day, but he still encountered it regularly. He sent patients off to hospital for scans that revealed they had tumours. On the way back to his car each evening, he stopped in and made the rounds of the local nursing home, where many were in a protracted state of decline, usually from dementia. Some of his other patients were heroin addicts; not all of them survived.

I thought Dad was old then, but he wasn’t, really. He had just been haunted and dying the whole time, right in front of me. At 36, I am already older than he was when he had me. After he died, three of my good friends’ fathers passed away in quick succession. The ones with cancer went slow, the ones that took their own lives vanished in an instant. Because it had happened to me first, I became an unofficial counsellor to them, a bunch of men in our late twenties, suddenly all very concerned with death.

Marcus Aurelius, the 2nd-century Roman emperor and stoic philosopher once again in vogue with self-help podcasters the world over, posited that knowing life could end tomorrow influences how you live it today. And while the deaths of those closest to me (whether familial or proximal) made me question how I move through the world, I would argue that what it really granted me was a level of empathy that I didn’t naturally have before. To make life less about my own mental state, in the traditional Stoic sense, and more about the mental state of those around me. Dad would have had a lot to say about this, I think.

I think about my neighbour every time I pass his widow and their gorgeous black dog on our staircase. He clearly left a lasting impression on the people around him, though I doubt he ever spent any time planning or thinking about his own funeral. My father famously hadn’t taken out life insurance when he died. We all live forever, until we don’t.

It took a long time for me to be able to listen to "All My Friends" again. It’s a song about being stuck between what you want to do and what you should do. It’s a song about regret, about the transience of friendships. But mostly it’s a song about ageing, which my neighbour never had the chance to do. James Murphy released it when he was 36—my age—as a reflection on the best years of his life. What if they had also been the final years of his life? Would the song have sounded different?

Either way, it’s possible Murphy would have written that famous refrain in exactly the same way: where are your friends tonight? This, ultimately, is what facing death has made me truly understand. Your best and only life is never just about you.

Originally published on Esquire AUS

I’d seen the word on social media. Mid. The show was mid. The song was mid. The rapper was mid. So many shows, songs, rappers and more are unknown to me, trees in the now-bewildering wilderness of pop culture that the young navigate effortlessly.

But I rapidly deduced that mid is not good. Mid is mediocre. Middle of the road. Meh.

And then I realised—I am mid.

The pandemic made my midness unavoidable. Until then, I could convince myself that I looked 10 years younger than I was, and looking good is halfway to feeling good. But in the Age of the Mask, my face of denial was shrouded. Suddenly all I saw were eyes. Nothing I did to my visage or hair could perform a trompe l’oeil and camouflage how my age was now inscribed in the lines and wrinkles around my eyes, underlined emphatically by a duo of bags that got heavier every year. The young, in contrast, showed off their youth effortlessly with the smooth and unblemished canvas framing their eyes. Every moment of fleeting eye contact with both young and old reminded me of the threat of mortal illness as well as the inevitable slow motion of ageing.

Funny how I trembled when I turned 40, more than a decade ago. How youthful 40 now seems. But I remind myself that at that middling age, when I wanted nothing more than to be a novelist, there was no published novel. I also had not wanted to be a father, that death sentence, yet that is what I became. When my son was born, my life, as I knew it, was over.

I was 42.

I had just finished the first draft of my novel, and my most important job was to watch over my son at night to make sure he lived. From late in the evening until 3am, I rewrote the novel while watching little Oedipus sleep in the same room, swaddled on the futon. Anytime he stirred, I stuck a bottle of formula in his mouth. From 3am until his mother took over childcare duty at 5am, I sipped my own formula—single malt Scotch—and wondered: Was I a failure? Was I ever going to publish this novel? Was I middle-aged? How does one know for sure?

Statistically, the average middle age for American men begins just past the mid-30s, since the average American male’s life span is 73.5 years of age. As a country, America can be considered rather mid, with the United States ranking below Albania and above Croatia. Hong Kong tops the charts at 83.2 years. Our average must be brought down by a daily drip of government-subsidised corn fructose and the lack of universal health care, as well as a toxic mix of economic inequality and depression, gun violence and opioids.

If I am statistically average, then I have been middle-aged for 15 years. I tell myself I am not afraid of Death. Easy to say until one sees the Great Funeral Director’s hand on the switch, ready to turn off one’s light. I will admit that with the shadow of mortality falling on my toes, I bought a sports car at the age of 43. A used grey Infiniti coupe with automatic transmission, the nicest car I had yet owned but far cheaper than a brand-new Honda Accord. Not a sports car by the definition of connoisseurs. Not a Corvette; not red. The car even had a back seat that could fit a car seat and my son.

Even my midlife crisis was mid.

I examined my son, destined to kill me and usurp me, at least symbolically. Cute little guy. Could he escape his destiny? Could I escape mine? Perhaps if I read him more books? Spent more time with him? Took him to more Little League baseball games? Thankfully, he quit baseball after a year, but then took up soccer with great enthusiasm. I bought him shin guards and cleats, watched him and his Neon Knights practise while I sat on a tattered beach chair, angling my umbrella to ward the sun off my pale legs. Was this happiness? Was this what a writer does?

The long middle of a story is the hardest part for me as a writer. The beginning, far in the past. The ending, I don’t know. But what I do know is that it is good for a writer to be unaware of the conclusion. If the end startles the writer, it likely will surprise the reader, too.

Pssst—the hero dies.

I didn’t hear that.

I used to think that writing was a ticket to immortality. Who needed children when one’s progeny was one’s books? In my teens and early 20s, I longed for fame and glory. I didn’t think much about how the names of the immortals were relatively few, while libraries were filled with thousands of books by writers I had never heard of before, some of them quite famous in their time. And some authors whose names dominated only a decade or two ago are rarely mentioned today, now that their life force no longer animates the literary scene.

When it comes to literary fame—which is not really that famous—I have more than some authors and less than others. But whenever I am tempted to believe my own hype, I read my one-star reviews — Bafflingly overpraised! Absurdist and repulsive! Pure garbage!—and recall that I live not far from Hollywood. When I tell people in Los Angeles that I’m a writer—no one cares.

And if no one cares, why should I?

That seems to be the greatest freedom in being mid, at least for me. To be middle-aged is not necessarily to be mid, particularly if one feels that one is at the peak of one’s powers. But to acknowledge that one’s accomplishments, great or small, hardly matter to most people and may one day fade into the dust, rendering one mid or even forgotten—might that actually be liberating rather than depressing?

When I was younger, I cared very much what people thought of me and my work. Part of me, because I am human, still does. But an even greater part of me does not. I had an inkling of what it meant not to care when I wrote my first novel; I was already old for an aspiring novelist.

I had written a short-story collection while yearning for the attention of editors, publishers and agents. When I realised that the power brokers did not care about my book or middle-aged me, I was free. Not to care. To do exactly as I pleased. Because I was mid.

It’s hard not to care in your teens and 20s. But as I looked at my son, turning two, three, four, I saw how he was almost literally carefree, except for wondering if he would get all the toys and treats he wanted. But he also simply did not pay attention to rules, expectations, conventions. You’ll find out, I thought grimly. That’s the way life is.

And maybe he will submit to the borders of adulthood. But at five years of age, he wrote and drew his own comic book, Chicken of the Sea, about restless chickens who run off from the farm to become pirates under the command of a rat captain. I was amazed. I could never have come up with that story. Because I cared about things like reality. How realistic. And how limiting.

So in my mid years, I try not to give a damn about unimportant things and unimportant people. The important people—friends and family, children and partner—still concern me. Writing, too, because it remains my passion. After I publish a book, I do keep an eye on how it fares in the world, vulnerable as I am to desire and vanity. But in the midst of writing a book—the art is all that matters.

The result is that the stack of books I have authored grows little by little, outnumbering my children in quantity. But never in height. Or weight. Or even, perhaps, in quality. If you had told me, in my youth, that I would be a father and love fatherhood and adore a daughter and a son I did not want or even dream of at the time, I would not have believed you. Down that road of family and stability, love and care, lay mediocrity. And perhaps that is true. But what is also true is that if my story concluded here, midway, I could live, and perhaps die, with being mid. Not the happiest of endings, but happy enough. And no one would be more surprised than me.

Originally published on Esquire US

Does the way I wear my hair make me a better person?

At 11 years old, I started noticing greys in my hair. I was naturally surprised but not really bothered—just a few strands at the back of my head that my mother vigilantly plucked out whenever they presented themselves. But then they started to appear more frequently. And barely a year later, the greys were sprouting all over the lower half of my head.

You can imagine how, as a pre-teen, having such a visible hair “issue” wasn’t the best thing for one’s self-esteem. It came at a point when I became obsessed about having my hair held down by copious amounts of hair gel—having greys meant that my school-going hairstyle wasn’t as slick as I’d like because grey hairs have a more wiry texture.

Plucking the greys proved to be increasingly painful and time-consuming. It may have been borderline therapeutic initially, but that quickly wore off as the number of greys grew exponentially. I settled on covering them using boxed hair dyes—a triweekly routine that I’ve grown accustomed to.

That’s the thing about hair: it’s such a major part of one’s sense of self. Anything that disrupts it from being what we perceive as the norm tends to be cause for personal concern.

Does the way I wear my hair make me a better friend?

“My hair has always been a part of my personality. When I was in my rebellious phase, I wore it really long. Then when I became interested in fashion, I changed course with more trendy haircuts. Any way you dress it, hair has always been my thing,” Bobby Tonelli tells me. The Singapore-based seasoned actor and host looks every bit the same youthful individual as when he first moved here in 2007. I tell him this. Tonelli thanks me and proffers, “When your hair is thicker, you tend to look fresher or younger. When it is thinner, people tend to relate that to looking older, you know what I mean? It’s a psychological thing."

One would think Tonelli is nowhere near the age when hair issues manifest, at least not in today’s society where people seem to be ageing more slowly than generations past. The reality—according to a study by University of Miami Miller School of Medicine published in 2020—is that men suffer a 50 per cent risk in developing hair loss once they hit the age of 50. A separate 2000 community study of male androgenetic alopecia (the most common form of hair loss) done in Singapore found that hair loss could start as early as in the 20s for men.

Tonelli’s experience seems to confirm the findings. It was in his 20s, while working as a model, that he started to notice some form of hair thinning. “I kind of noticed it. But when people doing my hair on shoots start pointing it out, I thought, ‘Oh ok. Maybe this is a bigger deal than I thought’,” he recalls.

Now at age 47, Tonelli is opening up about undergoing a hair transplant to fix lost hair around his crown and hairline. It’s been slightly over six months from the day he had the hair transplant and if I weren’t privy to it, it would never have crossed my mind that he had gone through an eight-hour procedure to harvest and transplant about 2,400 hair grafts from the back of his head. “I’m a mature male; I’m never going to get back that young hairline from when I was 20,” Tonelli acknowledges. “You want to create something natural and proportional. It’s been filled in a little bit to where I notice it, but not necessarily obvious to the average person.”

Does the way I wear my hair determine my integrity?

Graphic designer Juwaidi Jumanto, 31, would use his photoshop skills to correct a receding hairline in his photos. He too tells me that it started getting noticeable in his 20s. He would dabble with hair root makeup, anti-hairfall medication, and expensive hair treatments—“but once you stop going for them, the issues recur”—before finally investing in a hair transplant last year. “It was a personal goal. I wanted to get a hair transplant before I turned 30,” Jumanto shares. He underwent the procedure in May 2022 and says that he’s fully recovered with the transplanted areas already blending in with the rest of his scalp.

Jumanto cheekily attributes his receding hairline to his father who experienced the same issue. Pre-hair transplant, he shares that most people wouldn’t have noticed his receding hairline. “It’s more about how you feel about yourself. There were days when I’d wake up and the idea of my hair thinning away would affect my self-esteem. I did this for me,” he expresses.

Both Jumanto and Tonelli are part of a growing number of men opting for hair transplants. It’s a growing trend that has over three billion views on TikTok alone. Search for “#hairtransplant” on the social media platform and you’ll find numerous clips of hair transplant journeys—a majority of which shared by men. The clips are typically intimate and personal, bringing followers and casual viewers along the process from initial consultations to surgery day to recovery.

At the time of writing, John Hui—@thejohnagenda on TikTok—is into his 13th week of recovery since getting a hair transplant. He’s been detailing his journey weekly, capturing the realities of the recovery process. It’s a long one and visible results take a considerable amount of time, but in between, it’s often a rollercoaster wave of ups and downs. For example, Hui saw promising growth and he was elated with the shape of his hairline in week two, before things took a nosedive on week three with the development of scalp acne and a general sense of discomfort around the donor areas.

I am not my hair

“Hair is closely connected to self-confidence. The first impression that you give when people look at you, comes from the face and hair. Before I had my hair transplant, I would always subconsciously wonder if the people around me were thinking negatively about my hair,” Jumanto says. Tonelli elaborates that hair symbolises who a man is—their personality. “If you have a very nice, sharp crew cut, it’s like you’re clean and healthy,” he opines.

That’s not to say that having a lack of hair is, by default, a negative.

Hollywood celebrities embracing a relatively bare head are aplenty. Dwayne Johnson, Jason Statham, Laurence Fishburne and Bruce Willis are but a small number of A-list names who have transitioned from a full head of hair in their youth to almost none at all. I dare you to say that The Rock projects anything but a manly disposition.

For 33-year-old Joshua Simon, hair was getting in the way of living his best life. The Singaporean Radio DJ took the plunge to shave his entire head in 2019 and has kept it as such ever since. “I was in Bali and I had a villa with a pool, but I found myself not going into it because I was like, ‘If I get into the pool, my hair is going to get wet. And then I would have to dry my hair, and style it, and then it’ll take me so much time before I get to go out...’” Simon details.

He got into the pool eventually and emerged with an epiphany: “I knew that I wanted to look the way that I feel on the inside. And how I felt on the inside was free.” Simon broke away from the tyranny of hairstyling he has remained free to this day.

Prior to shaving off his hair, Simon was no stranger to experimenting with his mane—rebonding, colouring, faux-hawking and even leaving it in its natural curly state. But due to that constant experimentation, he found himself losing “chunks of hair” around the age of 19. “My mom suffers from some form of alopecia and so does my dad,” shares Simon. “It’s the scariest thing when you’re in your teens and your hair is falling out.” Thankfully, it happened right before enlistment into the army for National Service. Simon took the opportunity to shave his head and let his scalp heal.

I am not your expectations

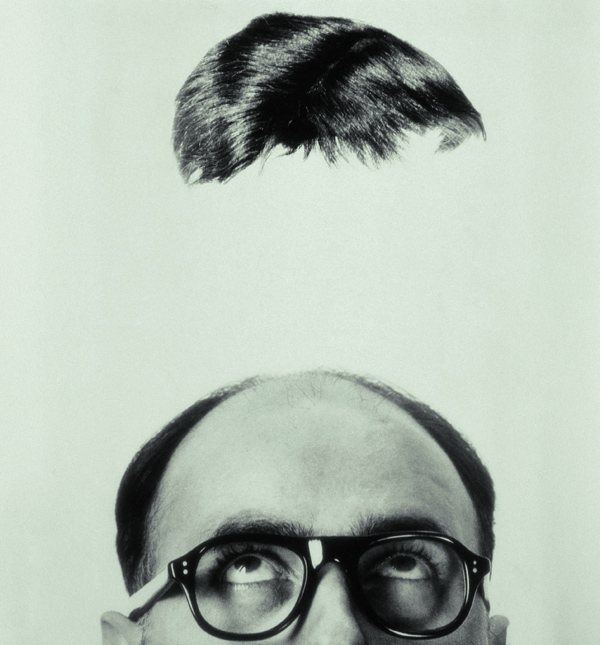

Hair issues are by no means unique to men. Women suffer from them too. While femininity is traditionally tied to having long, flowing hair, it’s the fullness that men are often judged by. It’s become a longstanding slapstick trope: a male character getting his toupee snagged off or blown away by a strong gust of wind, only to reveal a bald patch. Heck, we even ridicule Donald Trump for his combover.

The idea of hair being such an integral part of a man’s identity perhaps has little to do with being masculine—it has more to do with ageing and the denial of it. Society has conditioned us to desire looking younger than our age; to protect any semblance of youthfulness that has yet to be tainted by time.

Greying hair is undoubtedly a natural course of ageing. But prematurely greying while being in the throes of puberty? Not so much. The same goes for balding, thinning and receding hairlines. They are all inevitable effects of ageing across the gender spectrum. Sometimes though, for unclear reasons, it is possible to experience them when we’re not “at that age” and, understandably, not prepared to embrace them.

Having gone through a hair loss scare and embracing a buzz cut, Simon tells me that he has less of a fear of eventually losing hair as he ages. He still maintains his use of Propecia—a prescription-only medication for treating hair loss—to help keep what he already has. “I’m also mindful about not feeling shackled to it,” he says. “I don’t have the fullest scalp but even to have a semblance of this shape at my age, I’m grateful. If it continues to recede down the line, I’m super chill with it as well.”

Would he undergo a hair transplant like Jumanto and Tonelli? “I have thought about it. It’s also crazy expensive,” he counters. And it’s true. The latter’s procedure was an almost SGD10,000 investment. But Simon is not ruling it out.

At the end of the day, all three men agree that if their hair eventually succumbed to the test of time, there are no qualms about accepting the fact. But till that day comes, the proverbial crowning glory is getting the care and worship that it deserves, to better reflect the man that they each feel inside.

I am the soul that lives within