In 2010, David Allemann told his friends he was quitting his C-Suite job at the trendy Scandinavian furniture company Vitra to pursue something new.

“He messaged me on LinkedIn and said: ‘I’m going to start a running shoe brand’,” Alex Griffin recalls. “My reaction was ‘Good luck!’ Who needs that?”

Allemann had decided to go all-in on a project with his friend, Olivier Bernhard.

Bernhard, a retired duathlon champion and winner of multiple Swiss Ironman competitions, had approached Nike with an idea for a new shoe. Something intended to maximise the enjoyment of running, with a novel design that would cushion impact and propel the runner forward.

Bernhard said it would give the sensation of "running on clouds".

Nike passed.

So, he set about constructing his own prototype, slicing up a rubber garden hose and gluing sections to the soles of an old pair of Nike trainers.

“Please tell me you haven’t invested any money in this idea,” another friend, Caspar Coppetti, told him.

The design became known as "Cloudtec" and formed the cornerstone of On, the athletic brand Bernhard went on to found with Coppetti, and Allemann.

In 2021, 11 years after it began, On debuted on the New York Stock Exchange with a valuation of USD9 billion. Last year it reached almost USD2 billion in sales. The company has grown between 70 and 80 per cent every year for the last seven years, sealing its reputation as the world’s fastest-growing shoe brand.

It may just be getting warmed up. On has stated publicly its intention to double revenue by 2026, up to USD4 billion.

Its running shoes, typically with horizontal hollowed tubes lining the midsoles, described by one reviewer as looking like "short rigatoni pasta glued on from the sides", are now sold in 10,000 outlets in more than 60 countries.

Expansion has been so rapid, On has moved offices six times.

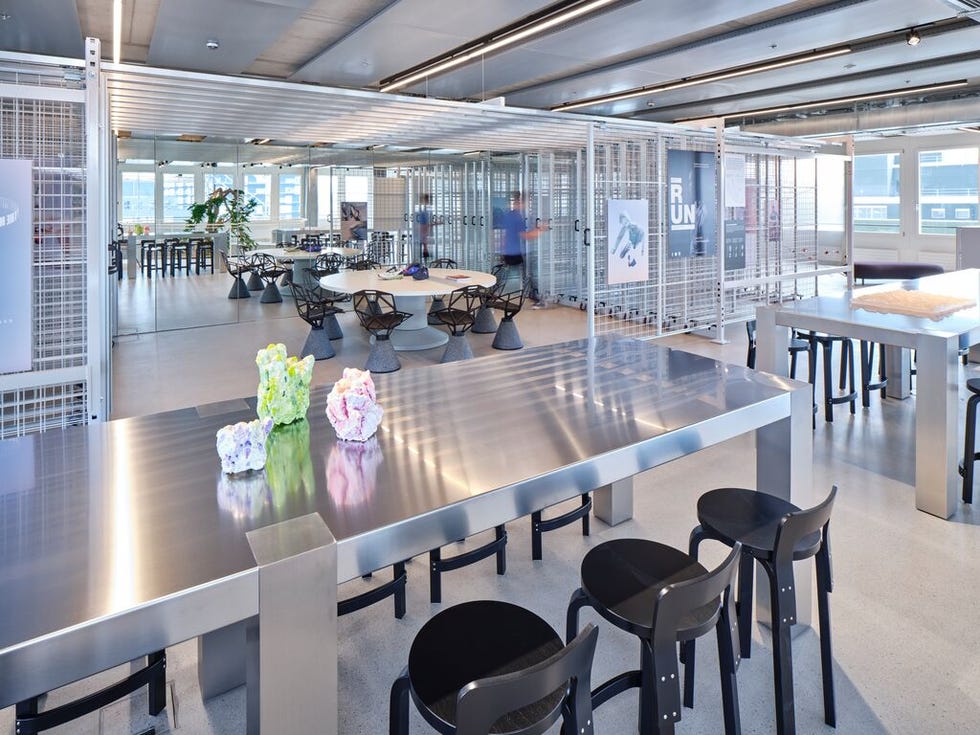

One thousand of its 3,000 global employees now share a purpose built, state-of-the-art head office in Zürich—On Labs—an imposing 14-storey building in the city’s former industrial district.

No one in On’s management team has any prior experience in either athletic shoes, or sportswear.

“Bring together a group of people who don’t know anything about what they’re doing and let them hack it out,” grins Allemann’s affable LinkedIn connection Alex Griffin, who joined as chief marketing officer seven years ago. “No one ever asked for a running shoe from Switzerland. So, we had to tell them.”

We are sat talking in the library on the eighth floor of On Labs, which, on a clear day, offers postcard views of the Swiss mountains. But I first meet Griffin in the lift, arriving for work with other youthful, lean and sportswear-clad employees early one morning in January.

On Labs shares many attributes with a tech start-up—modernist stone architecture, high-end canteen, ping-pong table on the roof—but also much that’s unique.

For starters, it’s in Switzerland. The country is associated with chocolate, luxury watches and private banking, but not necessarily innovation. It is famously conservative.

“The thing about being a Swiss company is that you know very early on that you have to go international,” Jiahui Yin, On’s fast-talking chief operating officer tells me. “Switzerland is a very small country. If you’re just a Swiss-based consumer brand you can never have a great level of influence on people’s behaviour. From Year One, we were already in Germany, and Austria. And then we went to the US in 2014.”

On’s Swiss qualities may be detected elsewhere, too. For all the noise made about the unusual soles on its shoes, the brand’s colours and overall designs tend are typically minimalist and neat. It found its first brand ambassador, also a serious financial backer, in Roger Federer, the 20-time Grand Slam tennis champion, a sportsman famous for his composure and calm.

His wife Mirka had started wearing Ons.

“At first, I thought that they were a little strange to look at,” Federer recalled. “Then I realised I actually liked them.”

It was Federer who approached On. They were not immediately convinced—what if the tennis legend was too famous? Might that overshadow the brand? (On’s resulting line of tennis shoes is known as The Roger.) Similarly, when Jonathan Anderson of the beloved fashion house Loewe approached On to suggest a collaboration, they took their time to chew it over—finally agreeing that Anderson’s love of craft and design would be an appropriate fit. The partnership is now in its fifth year.

On has recently signed two new ambassadors. One is the actor Zendaya, an idea that you suspect came less from the actor's enormous global fame and youthful appeal, than it did from her starring in Luca Guadagnino’s arty tennis drama Challengers. The other is the singer FKA Twigs—which initially appears like the most hypebeast signing imaginable, until you remember the star started out as a dancer and puts dancing at the centre of her videos.

Larry Eder, co-founder of the respected blog RunBlogRun, had written that when he met On’s management team around the time of its US launch, he was shocked that they already had a 10-year plan in place—not something he’d ever seen with any US shoe start-up.

The On staff I speak to say this wasn’t the case, but they agree that there is a circumspection at On that has created a different kind of corporate culture at the sportswear company.

“Sometimes we hire people who have been Adidas or Nike for 15 years and they come in with the expectation that they are the industry expert,” says Yin. “And their reaction is ‘Oh my God, everything is so different here’.”

Ah yes, Adidas and Nike. And, indeed, the rest of the running shoe market. As recently as 2020, Nike was outpacing everyone in the sport of running, its largest category. Now it seems to have caught a stitch. In December it announced it would cut USD2 billion in costs over the next three years, laying off staff to do so—a move that wiped 20 per cent off its share price. This followed an announcement that it would cut USD2 billion in costs over the next three years, laying off staff to do so. The brand is enduring the worst period since the late 1990s, discounting the pandemic and the Great Recession.

There is no single reason why. Internal corporate restructuring under a new CEO has coincided with an exodus of top designers, marketing gurus and seasoned executives. The company has ploughed a great deal of resources into the retro trainer business, capitalising on the seemingly bottomless appetite for vintage Air Jordans and Air Force 1s. New launches like the Book 1, a basketball shoe that came out in April, have failed to land.

Where Nike was once ruthlessly focused on marketing itself as the Just Do It performance brand— reinforced by superhuman sporting giants like LeBron James, Serena Williams and Michael Jordan—today its Instagram features a mishmash of shoes for toddlers and chore jackets for men, alongside football stars and Grand Slam winners. Most hurtful of all, Nike can no longer be said to be setting the cultural agenda the way it did in an era of adverts like “Dream Crazy” (2012) and “Failure” (1997). Given that the brand has been responsible for a run of the greatest marketing campaigns of all time, that may be a tall ask.

“We know we are not performing [to] our potential,” the brand’s CEO John Donahoe said in March.

In September it was announced that Donahoe would be succeeded as president and CEO by former senior executive and Nike lifer, Elliott Hill.

This year Nike celebrates its 60th birthday. It is not something it has chosen to shout about. On the other hand, retirement is hardly on the cards. Nike is still the world’s biggest sports brand by some considerable distance. Even when its quarterly sales are flat, those sales are USD12.4 billion. (Nike’s global revenue amounted to USD51 billion in 2023.) Along with Adidas, who which earned USD5.83 billion in the first quarter of 2024, even while it was still reeling from the implosion of its lucrative Yeezy partnership with Kanye West, it remains streets ahead of the competition.

The problem is there is now a lot of competition. In 2024, it is possible to divide the sportswear market in half. On one side, there are the incumbents—companies like Nike, Adidas, Puma, Converse and Vans, world-famous names with decades of experience and brand equity behind them.

On the other there are the challengers—brands like On, Hoka and Salomon. (Salomon’s roots go back even further than Nike’s—it started out making saw blades in the 1940s and has only recently seen its rugged trail footwear go mainstream, off the back of the Gorpcore trend. It is owned by the Finnish multinational Amer Sports, which also owns Arc’teryx.)

At this stage the chances of any one of them toppling any one incumbent are tiny. But collectively they are nipping at the old guard’s heels.

Consumer spending on sportswear, which includes labels like Lululemon, Sweaty Beaty and Gymshark, has jumped from USD301 billion in 2020 to USD422 billion in 2024. It is predicted to hit USD512 billion globally by 2027, according to a report published by the bank RBC in June.

That report also tracked specific brands.

As per analysis by the online platform The Business of Fashion showed that, between 2021 and 2023, revenue at 13 “challenger” brands rose by an average annual rate of 29 per cent, compared to eight per cent by the established names—the same period that Nike stalled.

It also mapped out the next few years. Between 2023 and 2026, RBC predicts compound annual growth of five per cent at Nike, nine per cent at Adidas and 13 per cent at Amer Sports, home to Salomon and Arc’teryx.

Way out in front, at 26 per cent, is On.

“Sportstyle” footwear—fashion-forward adaptations of running, trial and hiking shoes—has crossed over. While Air Jordans still command huge interest on resale sites and Adidas has had a strong run with its recent revival of terrace styles, there’s also been a shift with trainer aficionados, who appear to collectively to have woken up to the fact that half their collection is Jordans and the other half is Yeezys, and decided to switch up their rotation. In doing so, the giants have lost some of their swagger.

When Rihanna performed to a global audience of 121 million at the Super Bowl halftime show last year, she wore Salomon—albeit a pair of pillbox red M6 Maison Margiela x Salomon Cross Lows, a design more appropriate for looking incredible whilst being hoisted aloft on a silver platform and heavily pregnant, than, say, ascending Scafell Pike. (Designer fashion’s recent love-in with outdoor brands is not limited to trainers. See also: Gucci x North Face; Dior x Stone Island; Off-White x Arc’teryx.)

And where the hypebeasts and Rhianna go, regular guys follow.

Headlines like “What The Hell Is Going On With This Weird New Running Shoe?”(Gear Patrol, 2020, referring to Hoka’s bulbous neon-soled TenNine shoes) and “Why These Chunky, Ugly Running Shoes Are Selling Like Crazy” (CNN, 2023, about Hoka generally) would no longer be newsworthy.

Average Joes are now just as likely to be seen wearing trail shoes with thick-stack heels or outsized runners that encase a carbon-fibre plate between generous layers of lightweight foam, as they are Sambas.

On’s Cloudmonster Hyper is promoted with the legend “when max CloudTec® cushioning meets Helion™ superfoam, max energy is released”, which must certainly be a boon when doing the school pick-up

My taxi driver from Zürich Airport was wearing a pair of On Cloud 5 running shoes. So was the receptionist at my hotel. Neither looked to be in tiptop physical shape, no offence.

“Of course there’s a certain amount of athletic virtue-signalling,” says Alex Griffin. “The athleisure explosion has been part of that. It’s a visual choice for people—saying something to other people that makes them seem more sporty. But the comfort component is important. Shoes that are great to run in because they feel soft inside and give you good cushioning—they’re also good for the all-day.”

In contrast to other brands who that have maintained the party line that their products are designed strictly for sport, even when that product is a trendy limited-edition collaboration with a rapper, On readily concedes that many customers just want a casual, comfortable, everyday shoe. It’s here for them, too.

That’s a pitch that is both honest, and good for business.

“Everybody walks in shoes,” observes Jiahui Yin. “Walking, running, going to different locations. And so they can use our technology.”

“On has been able to cater to the lifestyle needs of a broad swathe of the population, in ways that others haven’t,” says Dylan Dittrich, head of research at Altan Insights and the author of Sneakeronomic Sneakonomic Growth: Scarcity, Storytelling, and the Arrival of Sneakers as an Asset Class. “And that’s kind of a double-edged sword, right? They haven’t necessarily been the supercool lifestyle streetwear sneaker of choice—yet. Instead, they’re selling that athleisure look with a little bit more sophistication. You see people from the Baby Boomer generation wearing them, you see millennials, you see Gen X.

“And that’s obviously conductive to growth,” Dittrich continues, “particularly in the earlier stages they’re in, relative to competitors. But they don’t want to be viewed as a ‘dad shoe’—at least, I assume they don’t —and I think you can see them figuring out how to take the next step, towards the more youthful, sneakerhead, streetwear segment. Zendaya is part of that. But it’s an ongoing, and early, effort.”

There is evidence it is already moving to capture the sneakerhead zeitgeist. Fashion branding was all over Paris during this summer for the 2024 Olympics, but there was one product that dominated the headlines—On's "lightspray" spray-on marathon shoe, launchd to coincide with the event.

While others had paid billions for billboard advertising, On drew a crowd to a small pop-up gallery near the Rue du Faubourg du Temple.

Inside a glass box, a robot arm delighted onlookers as it twisted and turned and sprayed material onto a mould to create a sock-like upper, with no laces.

The shoe would be launched at a later date.

As I stood and watched, Olivier Bernhard rode into the building on his bike, dismounted and was high-fived on his way through the onlookers.

Authenticity has been another driver of On’s success.

Just as, in the 1950s, Bill Bowerman, head coach at the University of Oregon, wanted to invent lighter, faster running shoes for his athletes and teamed up with his former student Phil Knight to found Nike, Olivier Bernhard dreamed of a shoe that would improve the running experience.

On’s first release, the Cloudracer, caught on initially with hardcore runners. On has maintained these roots, sponsoring On Athletics Club (OAC), a group of professional distance runners who primarily train out of Boulder, Colorado, organising weekly Run Clubs every Wednesday outside its 45 stores around the world and signing several recent Olympians to its roster, including American 10,000-metre specialists Alicia Monson and Joe Klecker.

“The OAC are a cool, interesting group of young athletes who will be competing at the Olympics this year,” says Griffin. “They live together, they train together—they’re a bit like a running cult.”

They live together because On sees benefits to this.

“They have an amazing coach, Dathan [Ritzenhein, a retired US long-distance runner] and togetherness is an important part of his process,” Griffin says.

“The OAC truly are friends—they have a podcast together, in which they talk about coffee, of all things [The Coffee Podcast]. They really do support each other. If one of them is racing and the others are not, they’ll go and support them. And that is different to other brands. Other athletes now want to become part of that. So, I think they see the difference, too.”

“On has started to become a more serious competitor in performance footwear,” says Dylan Dittrich. “Obviously having Roger Federer being such a big part of the brand is going to give legitimacy in tennis. But in running, they’ve built a first-class roster of athletes, and that’s helped the brand be taken more seriously. They’ve done a lot of things very well.”

And while a traditional athlete’s sponsorship deal might involve shipping a box of kit out to them every few months and possibly meeting up at a race, On’s “360-degree”approach provides its ambassadors with everything from training to nutrition guidance to financial advice. It’s an investment in building long-term relationships, in other words.

“We’re not just another Nike that gives them a lot of money, and ships products that Nike has already made,” Yin says. “We make them part of On. We even make a product specifically for some athletes if they have a special need. We really believe all the input we get from them can eventually be commercialised and that will add value to our consumer business.”

On’s emphasis on grassroots marketing is specifically alluded to in its IPO report, and the company keeps its eyes to the ground with a rigour that may seem obsessive.

“Obviously, our product is being utilised in all kinds of occasions,” Yin says. “But as a company, we almost have ‘running’ as a KPI. We do runners counts around the main running tracks around the world, every year, twice a year. We actually count how many runners are wearing our shoes. We keep that as a key measure of success, internally.”

So, they literally have people with pen and paper, totting up how many pairs of On shoes go past?

“It’s a bit more AI,” Yin says. “We use an agency who are able to capture pictures, and identify what each logo is. Because it’s important not to be overly caught up by your success. The sales figures are going up, obviously. People love our shoes. The brand is very hip. But it’s important for us to be true to the core of the product. We want to see that people are using our products in the right occasions. That people not only like the designs but that they are being used on the tracks. You could well be selling a lot of products. But if no runner is wearing it, eventually you’re going to lose in this game.”

Last year On realised its gear had become popular with young people in Liverpool, sections of whom have a penchant for dressing in one sportswear brand, head-to-toe. (Under Armour was a previous example.) These were neither the hip sneakerheads nor the dads Dylan Dittrich was talking about, but youths loafing about on the day-to-day, decked out in On.

The brand scrambled to establish a pop-up in the city, set up in conjunction with local running clubs and groups—its first outside London. “The Monster Den” was a 4,000sq ft space designed to “spotlight community, connection, and the joy of running”.

“We were aware of a lot of brand heat in the Liverpool,” Diana Dowling, On’s head of retail design told me. “And our strategy is to go where the communities are. The challenge is letting those communities know about our roots.”

This stuff tends to be done with a light touch. Last June, I happened across a packed-out event on the athletics track on Parliament Hill, in north London. It wasn’t the runners pacing around the eight-lane track that had necessarily caught people’s attention, but the freestyle rappers, fire-eaters, climbing walls and various other forms of free entertainment happening around them. Since I was with two bored kids (my daughters, aged 7 and 11) it proved a welcome distraction for a couple of hours. We sat on the grass and coloured in placards of a cartoon rat holding aloft the words “YOU GOT DIS”. One of them is still in my youngest daughter’s bedroom.

It took a while to dawn on me the event was sponsored—by On. It served as a kind of matinee to “Night Of the 10,000m PB’s”, part of On Track Nights, a global series of events that On’s website refers to as “the Glastonbury of the athletics world”. Later that evening, under the track’s floodlights, competitors including the long-distance runner Jessica Warner-Judd and the Olympic finalist Andrew Butchart raced for prizes, with the top award going to the two-time Olympic medallist Paul Chelimo.

“It’s important to get close to the community,” Griffin says. “That’s a great example of where we try and take running into the people. You might watch the London Marathon on TV. But running per se is not something that the masses tune into. So, we try to bring people really close to the track and hopefully feel the rush of the athletes as they as they go past, and well as doing some of the festival components around it. We call it ‘run culture’. This culture around running, which is not just, ‘Hey, let’s watch someone run and maybe break a PB.’”

How big does On’s senior management think the brand could become?

“Well, we have a big dream,” Yin says. “But it doesn’t matter how big you are, it’s really the quality of your growth. There are many examples in this industry where if you’re pushing for too much growth, you start doing the wrong thing. Like putting the wrong inventory in the wrong channel, and you start to diverge from what your brand authentically should be.”

On developed trail shoes, for example, because it realised its customers were using its padded running shoes for hiking. But it has no immediate plans to get into, say, basketball.

“We’re not going for something that is not relevant to us, if our customers are not taking us there,” Yin says. “We still have so much demand just on our running products, and then the verticals that are adjacent to running. It’s a massive market.”

On has made one part of its big dream public: telling its shareholders it will hit USD4 billion by 2026.

Is that realistic?

“What we’re looking at is basically doubling our revenue,” Yin says. “We are quite confident we can do that. As of today, we are at almost USD2 billion. Look at Nike, they are 10 times that [actually more like 25 times]. But if you look at our brand awareness, and how much we are present in the different verticals, we are nowhere. There was an awareness test that we did in the US [On’s biggest market] and only nine per cent of consumers knew our brand. So, you can see how much room for growth there is. When we do our runners’ count, we are still a single digit percentage in how many runners on the major running tracks around the world are wearing our products. That also gives us a strong conviction that we can grow, quite significantly.”

“We actually could have grown faster,” says Griffin. “But we always wanted to do things in a qualitative way. We’re trying to invest in the right way—in our athletes, for example. Which is more about longevity than quick wins.”

It helps that, after football, running has become the world’s most popular sport. According to a report published in January by the data company Statista, 50 million people in the US alone participated in running or jogging in 2021, the year of the most recent figures. Post-pandemic we may consider ourselves to be in running’s second wave—the most accessible, most effective form of exercise hasn’t been this trendy since the jogging craze of the 1970s.

Running clubs are the new social meetups. Apps like Strava and Map My Run encourage us to share our progress and PBs. The Apple Watch puts fitness and movement at the centre of its appeal. Half-marathons have evolved from being a niche endurance challenge to a mainstream fitness goal. Staying in shape is trendy. Just like anything else you care to name, running is big on TikTok.

When On floated on the New York Stock Exchange in 2021, its co-founders and staff helped make up a group of 100 runners, who ran together alongside the Hudson River over to Wall Street and up to ring the NYSE Bell.

“No one wore a suit or a shirt,” Yin remembers. “We were told ‘We don’t have facilities for a shower. But you’re welcome to come as you are.’”

(Founder Olivier Bernhard is known to do staff appraisals and onboard new members while taking them for a run around the shore of Lake Zürich. On the one hand, that must be great for team bonding. On the other, it’s perhaps not the way everyone wants to interact with their boss.)

My first encounter with the On team came in October last year.

They were two days away from opening their second UK store, after the flagship on London’s Regent Street. The more compact outpost—known as a “chapterstore”—was in Spitalfields, in east London. It has been chosen largely because the area was popular with runners.

“On Saturday morning we’re expecting 200 people from our community,” Emily Thompson, the brand PR lead at On in the UK, told me, as staff unpacked boxes and put shoes on shelves.

“Ambassadors, micro influences, too. Our team are mapping a route. We’ll figure that out.”

The staff were looking a bit sweaty themselves. They were just back from their lunchbreak. They’d spent it together on a run.

Humans have run for hundreds of thousands of years without the need for colourful, squishy slabs of foam strapped to their feet. Seventy years ago, Roger Bannister ran the first sub-four-minute mile in a pair of running shoes that looked like Oxfords with running spikes nailed through them. In 1978 Nike invented its Air Cushioning Technology: pressurised air embedded into polyurethane, previously used for create space helmets used in Apollo missions. In the early 2000s, inspired by Stanford athletes who were training barefoot, it began work on Nike Free, a reduced-weight shoe to make runners feel more connected to the ground. Oddities like Vibram’s FiveFingers, essentially rubberised gloves for the feet, followed.

“The biggest change that’s happened in the last seven or eight years is in foam technology,” says Dr Dustin Joubert, assistant professor at the Department of Kinesiology at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, who studies developments in running shoe technology. “Going from EVA [ethyl vinyl acetate] that you would get in your standard running shoes, to PVA [polyvinyl alcohol] based foam. It’s more compliant, so it stores more energy, and it’s more resilient, so it returns more energy. And that’s what’s led to improvements in performance.”

The most notorious example of this came in 2017, with the introduction of Nike’s Zoom Vaporfly 4% shoe, its name derived from lab tests that showed it improved running economy by an average of four per cent. (A furore about how much help was too much help in the sport followed.)

These days almost all running shoe companies have some PVA shoes in their line-up—though Joubert points out it depends how it is used, that every company has different patents, and just saying you have PVA running shoes is “like comparing two things that are made of plastic”. (He does study this stuff for a living.)

The amount of PVA varies across On’s line-up, with its enormous Cloudboom Echo marathon racing shoe leading the way.

“They’ve kind of minimised the amount of ‘garden hose’ tech in that shoe,” Joubert says. “Compared to the shoes you see in people’s daily wear. In the States we joke that Ons and Hokas are hospital workers’ shoes. They tend to be worn by people on their feet all day. But that’s always been the case with sneakers.”

When we speak Joubert is in his lab testing out a pair of new “USD500-plus” Attiva running shoes that strip out most of the PVA foam in favour of a mesh material.

“We may see things going the other way again,” he says. “There’s always a benefit versus a penalty, with every design. There’s an energy cost to all that extra mass. Too much foam can be detrimental. Also, they’ve got the energy efficiency of PVA up to 90 per cent now. There’s not too much further you can go with that.”

One of the secrets of On’s success has been attributed to its enthusiasm for product innovation: as well as the footwear for running and running-adjacent activities, it has an ever-expanding range of ‘top-to-toe’ apparel and accessories.

Although some four hundred people are employed in On Labs’ R&D, the company is keen to underline that any new piece of kit is a team effort.

“In a typical company you’ll have a product strategy team that writes a brief,” Yin says. “‘Hey, this is what the consumer wants, this is what it looks like, go out and do it’. And then the development team would look for the material and put the product together. At On we make sure every team has a say at that product ideation phase. Maybe we make a product based on something new in engineering, or based on strategy, or based on something the design team has come up with. But there’s always a lot of collaboration. An idea can come from anywhere.”

While there’s been no shortage of ideas, getting them prototyped has sometimes been a problem.

Olivier Bernhard is a habitual tinkerer, as befits someone who glued bits of hose to a shoe, often found customising bikes in his workshop in Heiden, in the Swiss countryside. He grew impatient waiting for his Asia-based factory to run-up samples, so he built a "Maker Space" on the ground floor of On Labs instead.

Now, when someone comes up with an idea the team can use PVA, a laser-cutter and a 3D printer to create a protype shoe in a matter of hours.

At On Labs I’m welcomed into the Maker Space by Thor ter Kulve, who runs the workshop. It is pleasingly old-school—tools lie scattered over benches and there’s a strong smell of solvent hanging in the air. The raw prototypes On makes are known as “monsters”.

“Because,” ter Kulve explains, “they are so ugly”.

“This is an example of the CloudSurfer,” he says, holding up an aborted version of the brand’s road-running shoe. “The idea was if we change the sizes of the cavities in the midsole and where they are placed, we can positively influence the way someone runs.”

It had so many holes in it, it looked like a block of cheese.

“You know, we all laugh about this Swiss cheese,” ter Kulve says. “But On was founded on this idea of cutting a garden hose into little sections and gluing it onto an existing shoe. And it’s that mentality we like to keep alive.”

On’s flagship Swiss store is connected to On Labs, a 350-sqm shop built with the same bright, industrial aesthetic as its offices.

Here I meet Bianca Pestalozzi, general manager for the EMEA region. She walks me though the entire range, and highlights On’s concealed Magic Wall shelves, which hold every fit of shoes—the quicker to get them into customers’ hands and onto their feet.

“Usually in a shoe store, the journey is a bit broken,” she explains. “A store associate vanishes around the back for 10 minutes to see if they’re got your size in stock. We wanted to disrupt that.”

Customers are encouraged not just to try the shoes on, but out—and go for a quick run around the block.

Another novel idea is On’s Cyclon line, sportswear that has been designed to be recycled. While every brand under the sun must now do something to tick the sustainability box, Cyclon’s offers something different. The line, which to date comprises two shoes and a t-shirt, is available by subscription only. You pay a monthly rental fee and when the kit is trashed, you return it for a replacement. On recycles what you’ve sent back. (Because it is all undyed, part of the appeal is surely destroying a pair of pristine white foam shoes.)

“We had to think about how we would go to market with that,” says Griffin. “People aren’t used to sending shoes back. At the end of their life, they end up in a recycle bin, if you’re lucky. So, the idea was a shoe that you never actually own. That’s a mindset shift. At the end of its lifecycle, when you’ve put them through their paces, and hopefully done some good kilometres, you get new ones.”

It brought to mind Nike’s Space Hippie, a line of trainers the company launched in 2020 “inspired by life on Mars—where materials are scarce and there is no resupply mission. Created from scraps, or ‘space junk’, Space Hippie is the result of sustainable practices meeting radical design”, it said.

The shoes looked amazing, a mishmash of colours and shapes that resembled futuristic pre-school junk modelling.

Nike produced a short promotional video to advertise the line, complete with a portentous eco-voiceover (“We’re in a race to save ourselves!”) showing its goodlooking staff cheerfully hand-assembling pairs in the Nike factory from offcuts and scraps they’d swept up off the floor.

This may very well be how the shoes are made, though it seems a bit farfetched. Either way, the vast majority of the 1,436 comments currently under the video on YouTube remain unconvinced by the project’s ecological bona fides.

‘I bet that factory is really good for the environment’ says one.

‘Close sweatshops & reduce your catalog [sic]’ suggests another.

On the wall of On’s flagship Swiss store is Olivier Bernhard’s prototype shoe. An old Nike covered in masking tape, with bits of garden hose glued, quite badly, to its base. I express surprise not just at seeing it, but that it exists at all.

“We didn’t make it up!” says Pestalozzi. “That’s how it all started.”

It is almost lunchtime and we are passed by a flank of young On employees kitted out in athletic gear, many of them wearing yet-to-be-released test shoes, jogging through the store. Despite it being -2°C, January and snowing outside… you guessed it, they’re off on a run.

“You don’t have to be a runner to work here,” insists Yin. “It depends how much you want to exercise. But we believe everybody does some form of movement.”

The only branding on the shopfront is On’s hieroglyph-like logo. It is supposed to resemble a light switch, turning “on”.

I say that I’d read that nine out of 10 people couldn’t decipher it, and don’t actually know what the brand is called. But surely that couldn’t be true.

“I actually think that it is true,” Pestalozzi says. “A lot of people think we’re called ‘QC’.”

“Somebody at my onboarding said it looked like a small penguin,” says Yin. “Loads of people tell me ‘Oh, I recognise the logo. But I didn’t realise you were called ‘On’.”

“We’re also aware of the limitations of the word ‘On’ in search term marketing,” nods Pestalozzi. “We’re taking steps to address that.”

“Still, given all that,” she says, “we’re doing pretty well.”