Since the rise of cinema from the late 1800s, films have done more than just entertain. They’ve informed us who to be, how to feel, and sometimes how not to feel. The way cinema has portrayed masculinity says a lot about the decades it comes from. Growing up, most adolescent males learnt how to be men not just from fathers or uncles, but also from the big screen. Whether we realise it or not, film has been quietly shaping what “manhood” is supposed to look like.

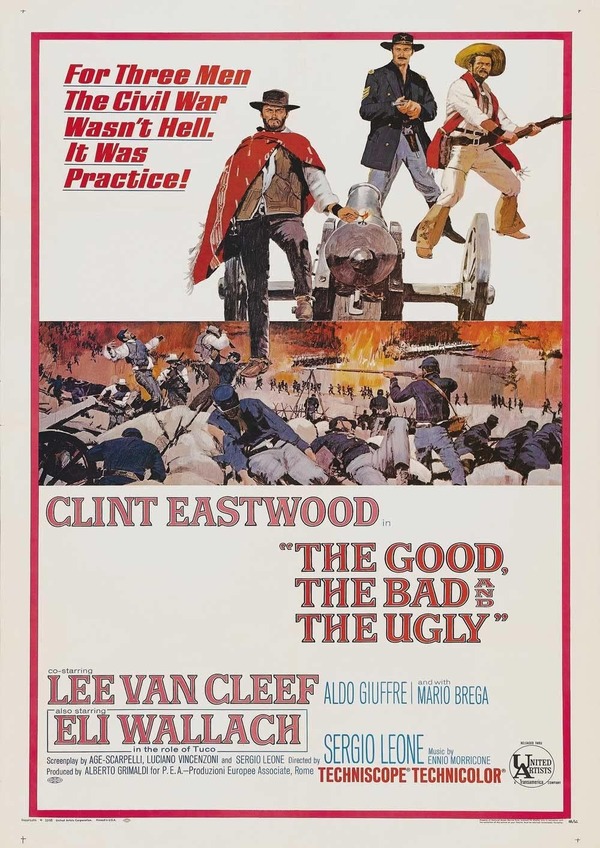

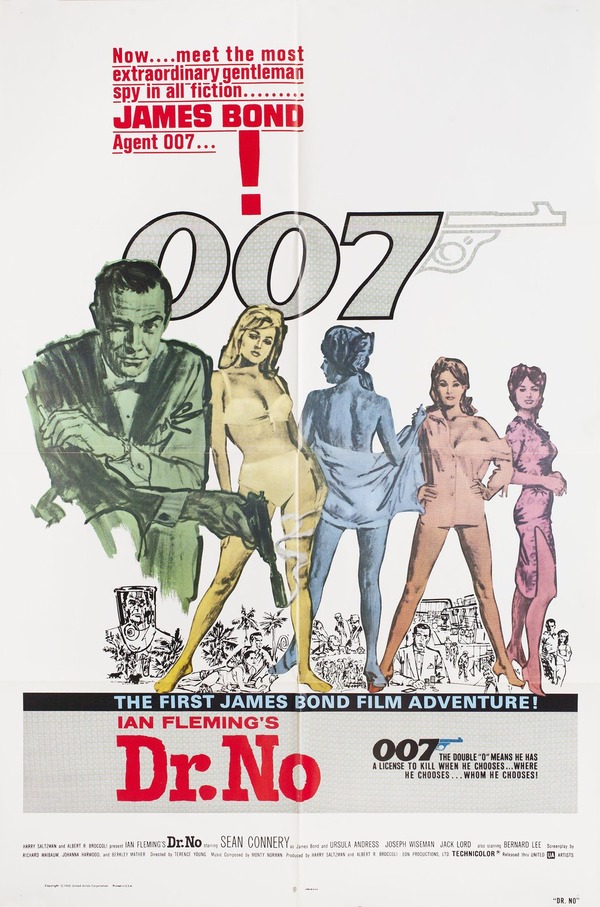

Since local cinema wasn't as established back in the '60s, young Singaporean men often watched Westerns. The idea of a man was straightforward; be tough, don’t talk too much, and win the fight. It was the silent but deadly archetype, embodied by Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and James Bond in Dr.No. For Singapore audiences, these men weren’t relatable, but they were aspirational. Our fathers (or grandfathers) wore singlets or shirts tucked into high waisted shorts, but somewhere deep down, they may have wanted to walk into a room like Eastwood and Bond.

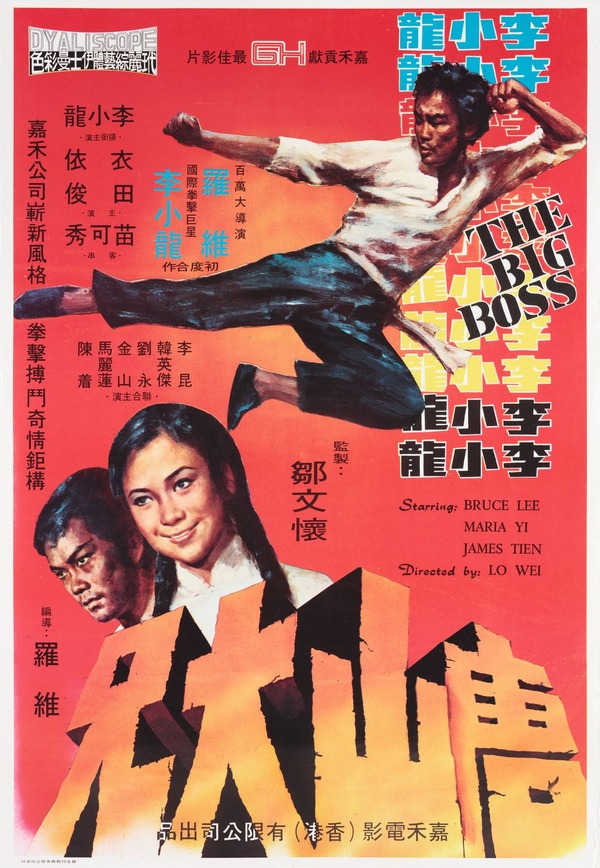

With a new decade, a new look to masculinity was introduced. There was a clear shift from the cold and calculated to physical and fiery. Bruce Lee kicked his way into global consciousness with his films about a small man fighting to receive respect throughout the '70s. He wasn’t some foreign hero in a cowboy hat; he was Chinese like us (or at least most of us). He showed Asian men that they could be powerful without being just a sidekick or the villain.

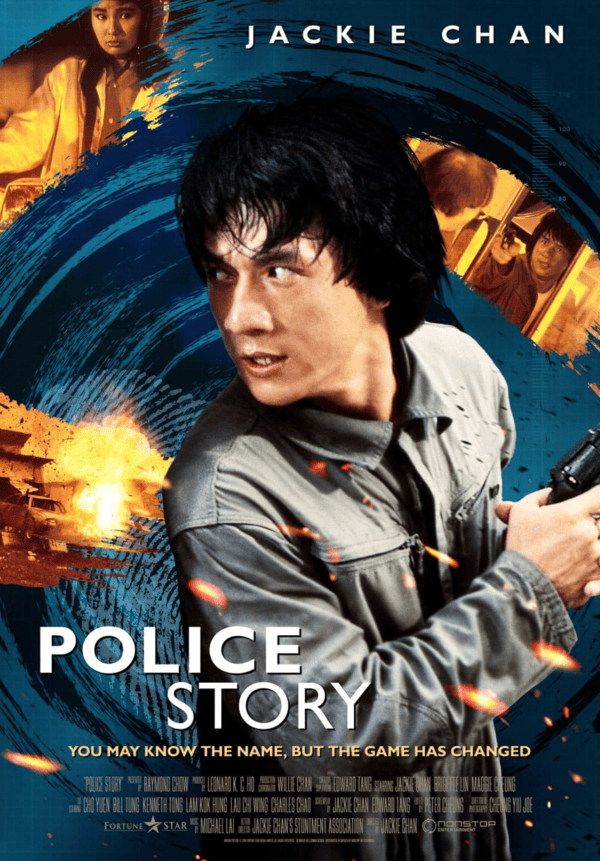

By the '80s, films were all about action. It was the decade of explosions, muscles, and one liners. Jackie Chan’s Police Story and Chow Yun-Fat’s A Better Tomorrow presented two sides of the same coin. A cop who does the right thing but breaks a lot of glass in the process, and the gangster with a moral code. Both were loyal to a fault, both could throw a punch; and both were, in their own ways, trying to be “good men” in a corrupt world. And with that, young men were taught to fight for a purpose.

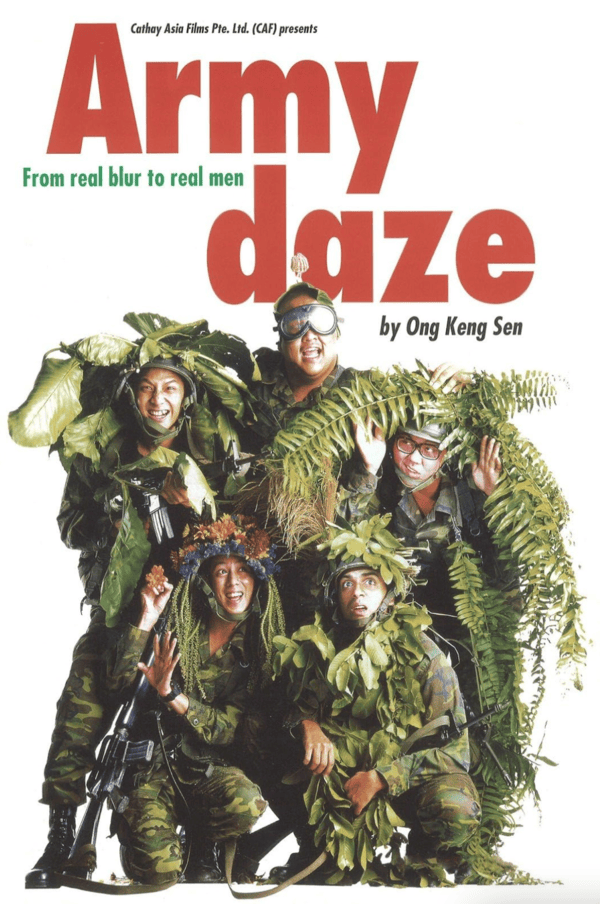

These weren’t just light-hearted comedies or nostalgic gems, but a reflection of everyday life packed in a way that was raw and relatable. Army Daze gave a coming-of-age lens into National Service, an experience every Singaporean son knew was inevitable. It was the first time they saw their own fears, frustrations and friendships played out on screen. Then came Money No Enough, which stripped away any remaining illusion of adulthood being easy. The film captured the relentless grind of trying to provide for family in a rapidly modernising Singapore.

The 2000s was chaotic, let’s be honest. It was a decade where boys matured in society that felt both restrictive and restless. Royston Tan’s 15 ripped the curtain back on the lives of troubled youth while offering a documentary-like glimpse into the YP culture. Then there was Jack Neo, once again showing a different yet equally painful portrait of kids suffocating under the weight of expectations in I Not Stupid and Homerun. These narratives were not just pure fiction. They were warnings about what happens when a society values success over sanity.

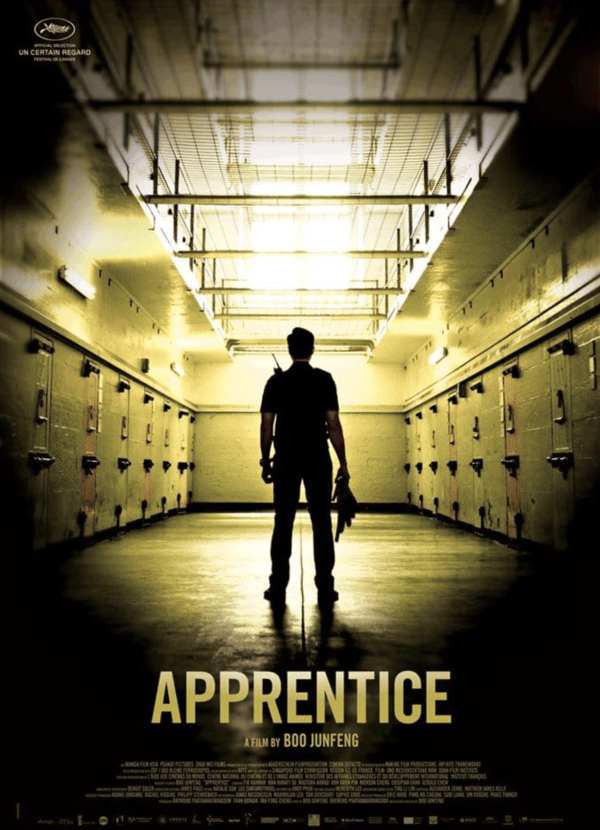

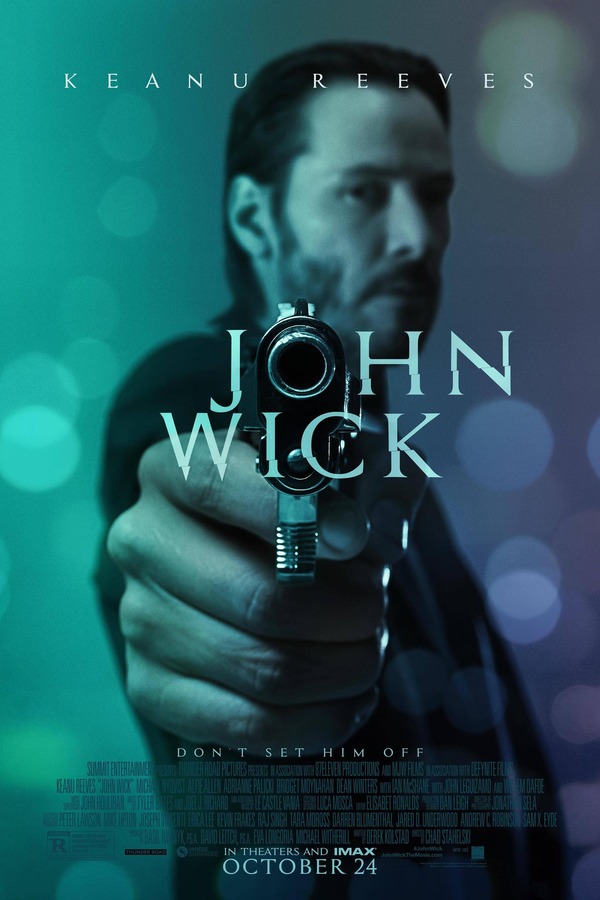

The 2010s was a strange, complicated decade where films reflected that shift. The Apprentice forced us to look at the gritty, uncomfortable parts of life inside the system. It wasn’t necessarily a story about good and bad, just ordinary people stuck in a machine bigger than themselves. The takeaway: Adulthood isn’t always about right or wrong, but about learning to survive in grey areas. In tandem, under all the violence of John Wick was a film about grief. How men may not know how to mourn properly, and rather channel that pain into carnage because that’s the only language they’ve been taught.

Films today are beginning to explore sides of masculinity that older cinema often overlooked. Lessons that crying doesn't make you weak; that acknowledging your feelings is not only acceptable but healthy; and that silent bravado is no longer the way to cope. There’s more room than ever to speak openly about emotional struggles and the reality of not always having everything under control. Films like Wonderland and Tiong Bahru Social Club create space for vulnerability and inadvertently became cultural checkpoints for manhood in Singapore. These stories don’t romanticise self-destruction, nor do they reduce men to heroes or villains. Instead, they allow them to simply exist as people in their most authentic self.