It’s all about the dog.

The teaser trailer for the new Superman film—called, simply, Superman—features no voiceover, no narration, no exposition and no information about its cast. There is no title card. It contains just five words of dialogue, which come prefaced with a whistle.

It opens on an icy landscape. The titular superhero, played by a young actor you probably don’t recognise, smacks down to Earth from the sky and lies still, sparked out in the snow. But then, as blood oozes from his face, Superman put his lips together and blows. Across the frozen tundra, something barrels towards him at speed, answering his call.

“Krypto,” Superman gasps. “Home. Take me home.”

Krypto is Superman’s pet dog, a small white mutt who possesses super-strength and can run faster than the speed of sound. He also wears a cape.

“Take me home” is a line that works on a couple of levels. Superman being rescued by his pet dog; and Superman’s bloodied on-screen reputation being rescued, possibly also by his pet dog.

“Krypto is the epitome of something that’s really daft and silly, but also has a lot of heart,” says Dr Mark Hibbert of the University of the Arts London’s Comics Research Hub. “But superhero comics are daft. And it’s much harder to convey that in a film than just Batman hitting Joker in the face.”

“Superheroes are either goofy or they’re fascists,” says Ian Gordon, author of Superman: The Persistence of an American Icon. “And people are more interested right now in them being goofy. We’ve had too much of the kind of darkness of Watchmen and The Dark Knight. It’s been played out. It’s narratively exhausted. Everybody I know who studies comics has homed in on Krypto. His appearance has given a lot of people hope.”

According to the lore, Superman shouldn’t need saving. He is the original comic-book superhero, who popularised the genre and established its conventions. His story is pseudo-biblical: born on the dying planet of Krypton, his parents placed him in a spaceship as a baby, like Moses into his basket, and sent him to Earth. There, he was discovered by the wholesome Ma and Pa Kent, who raised him on a farm in Smallville, Kansas, and taught him to uphold “Truth, Justice and the American way”. Since his creation he has been inextricably linked, in fact, with formative ideas of America: he’s a chisel-chinned, all-powerful entity, driven only by the desire to protect and a compulsion to do good. Yet the character, which is owned by DC Comics, has spent decades being unable to catch a break. Perhaps it’s a Superman problem: his super-strength makes it famously difficult to bring convincing jeopardy to his storylines. Perhaps it is a casting problem: few actors have managed to recapture the easy charm of Christopher Reeve, star of the first four film versions. Perhaps it’s a sociopolitical problem: it’s hard to get behind an avatar of American greatness at a time when the USA’s stock—at least externally—is at an all-time low.

Whatever the cause, up against the box-office kryptonite of his rivals over in the USD30 billion Marvel Cinematic Universe, Superman’s super-strength has been rendered all but impotent.

By consensus, the last good Superman movie was the first one, which came out in 1978. I was six when it was released, and it made me a comic-book fan for life. As the first superhero film millions of children would have seen, its wholesome humour, clear morality and magical flying sequences had many of us fashioning homemade capes and jumping off garden walls.

Superman: The Movie starred a then-unknown Christopher Reeve in the role that defined him. The screenplay was by Mario Puzo, who wrote the three Godfather films as well as the original novel; it was directed by Richard Donner, who made The Omen; it featured production design by John Barry, who won an Oscar for his work on Star Wars; and it starred an ensemble cast that included Marlon Brando, Gene Hackman and Ned Beatty. It was the second-highest grossing film of the year, only beaten—and not by much—by Grease.

At that point it was also the most expensive film ever made, and thanks to then-groundbreaking special effects (“You’ll believe a man can fly,” was the poster’s memorable tagline) it was nominated for four Oscars and won one. Reeve signed on for two sequels, and was strongarmed into a third, Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987), which bombed. After that, any notion of a Superman film spent two decades banished to the Phantom Zone.

There were reboots in 2006 and 2013, which earned decent money but not much love from the critics. Both attempts suffered from studio interference and creative stumbles, with the first, Superman Returns, starring Brandon Routh, being criticised for its lack of identity and undercooked action sequences, while the darker tone of the second reboot, Man of Steel, with Henry Cavill, was seen as divisive, with many feeling it at odds with Superman’s traditional optimism.

Things hit a new nadir with 2016’s relentlessly grim and grimy Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, starring Ben Affleck and Cavill again, and directed by the somewhat polarising Zack Snyder.

Now, 47 years on since Superman: The Movie’s cinematic high, a new film will attempt to lift him up, up and away once more. This time it has been directed and co-written by James Gunn, who was responsible for the recent Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy.

Those films brought humour and heart to a saturated superhero market, via the unpromising medium of some D-list Marvel characters, which even some serious comics fans struggled to identify—a group of intergalactic 31st-century outlaws that included a giant walking tree called Groot and a sarcastic, hyper-intelligent raccoon named Rocket. But the Guardians of the Galaxy films were critical and commercial hits, as was Gunn’s The Suicide Squad, made in-between for DC (less so on the commercial side, due to the pandemic), and in 2022 he was named co-chair and co-CEO of DC Studios. He has been planning a new DC Universe with a group of writers ever since; the teaser trailer for Superman is our first glimpse.

David Corenswet is the American actor in the spandex this time, though the trailer also shows him in his guise as Superman’s bespectacled alter-ego, Clark Kent, bumbling about the offices of The Daily Planet, the newspaper for which he works as a reporter.

Superman and his perennial love interest Lois Lane, played this time by Rachel Brosnahan, embrace, mid-air. The icy location where he whistles for Krypto is surely in the vicinity of the Fortress of Solitude, Superman’s hidden Arctic sanctuary, and a major feature of the early films.

Then there’s the music that plays over the top of the whole thing, a version of “Superman: Main Theme”, John Williams’ deathless original score. Rendered on electric guitar it somehow becomes even more elegiac, and it’s surely no accident that, because of this, it now recalls the theme from Top Gun, another iconic property recently revived to acclaim across the generations.

(In a comparable exercise, in 2015 JJ Abrams brought tears of joy to millions of middle-aged men by releasing a trailer for Star Wars: The Force Awakens that looked, sounded and felt like the original Star Wars film from 1977. In the otherwise dialogue-free teaser, we watch Han Solo and Chewbacca set foot in the Millennium Falcon for the first time in decades, and the former say to the latter: “Chewie… We’re home.”)

The 2025 Superman trailer unambiguously drilled that same well of nostalgia, echoing Reeve’s colourful and lovable performance from all those years ago. As Ian Gordon says, the teaser, viewed 58 million times in four months, has given a lot of people reason to believe (in the comics, by the way, the “S” on Superman’s chest represents both his family crest and a Kryptonian symbol for “the concept of hope”).

If Gunn can deliver on the trailer’s promise and rekindle our love for the Man of Steel, it might be his greatest feat yet.

Superman’s earliest iteration was not in the films, of course, but as one of several anthology stories in Action Comics, which published its first issue on 18 April, 1938. There had been comic strips and comic characters before, but they were mostly humour—(Felix the Cat) or adventure-based (Tarzan) and serialised in newspapers.

Superman’s creators were Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, a pair of quiet, intense Jewish teenagers from Cleveland, Ohio, who had met in 1931 and bonded over their love of the emerging new genre of science fiction. Siegel wrote up a story called “The Reign of the Super-Man”, a name coined by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche some 50 years earlier, which Shuster illustrated. The first “Super-Man” was a bald madman who tries to use his telepathic abilities to conquer the world. Not someone to root for.

But then Siegel flipped the script, making his protagonist a hero not a villain. He became a refugee from a distant planet and came clothed in an early version of his signature outfit, based on a contemporary circus-strongman look. The addition of the flamboyant costume helped bring another idea crucial to the character’s enduring appeal over the last eight decades.

“When all the thoughts were coming to me, the concept came,” Siegel recalled, “that Superman would have a dual identity, and that in one of his identities he would be meek and mild, as I was, and wear glasses, as I did.”

“[Superman’s] fake identity was our real one,” wrote cartoonist Jules Feiffer in the 1965 book The Great Comic Book Heroes. “That’s why we loved him so.”

“Superman made his position plain,” writes Grant Morrison in his 2011 book Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero. “He was a hero of the people. The original Superman was a bold humanist response to Depression-era fears of runaway scientific advance and soulless industrialisation. We would see this early incarnation wrestling giant trains to a standstill or bench pressing construction cranes. Superman rewrote folk hero John Henry's brave, futile battle with the steam hammer to have a happy ending."

Siegel and Shuster had hoped to sell Superman as a newspaper strip, which would provide a steady income of royalties, but were rejected by everyone they approached. Later, they were asked by National Allied Publications (later, DC) to rework their idea into a 13-page story to be the lead tale in a brand-new book, Action Comics. The pair were paid a one-time fee of USD130 for their efforts in a work-for-hire agreement, a deal that led to decades of legal wrangling and public outcry, until an eventual 1975 settlement gave them a credit on all future comics, films and media, plus USD20,000 per year compensation.

Action Comics #1 become a sensation on the news stands. Within weeks, most of its 200,000—copy print run had sold out. In summer 1939, the lead character was given his own title, a highly unusual move at the time. Superman #1 sold more than one million copies. The following year, The Adventures of Superman debuted on radio stations across America-within a year an estimated 20 million listeners were tuning in each week. Animated shorts in the cinemas and live-action serials on the television followed, notably the portrayal by amateur boxer and stage actor George Reeves, whose wholesome and optimistic Superman struck a chord in 1950s America.

By 1958 there were seven different Superman titles, collectively selling four million copies a month. But there was competition. Under the leadership of Stan Lee and with the creative input of artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, rival outfit Marvel began to introduce characters with more modern twists and complications. The September 1965 issue of American Esquire featured Marvel heroes Spider-Man and The Hulk in a list of 28 "college campus heroes", along with John F Kennedy and Bob Dylan not a DC hero in sight.

"The superhero stories that had dominated American comic books in the late 30s and 40s had mostly fallen out of style at that point," writes Douglas Wolk in his tremendous 2021 book All of the Marvels: An Amazing Voyage into Marvel's Universe and 27,000 Superhero Comics. "Kirby, Lee, Ditko and their collaborators figured out how to make the individual narrative melodies of all their comics harmonise with one another, turning each episode into a component of a gigantic epic. Ever since then, its writers and artists have been elaborating on each other's visions, sometimes set in the same place and time but often separated by generations and continents."

Against a backdrop of political and cultural unrest in America, Superman's "big blue boy scout" character was indeed looking a little hokey. In 1966, DC's number-two hero Batman came to TV in a straight-faced parody of comic book heroism starring Adam West ("Zap! Pow! Biff!"). By the 1970s, Saturday-morning cartoons, prime-time TV and video games provided more accessible forms of entertainment for young people, driving interest away from comics.

There were some logistical problems for the writers, too. One of the biggest challenges of Superman has always been his power set: he is invulnerable, has unquantifiable strength, can run faster than a speeding bullet, see through walls and fly. At various points in the comic books, he has used mystical chains to separate Earth's continents (World's Finest #208), magnetically held the Moon in orbit (JLA #7) and contained the power of a black hole in the palm of his hand (JLA #77).

What plausible threats to his invincibility are there in the known universe and beyond? There's always Kryptonite, of course, the green glowing material from his home planet that limits his ability to absorb power from the sun. Failing that, there's the conceit that Superman loses his powers in some way, eg: Lex Luthor inventing some dastardly machine, or a convoluted story in which he trades abilities with another superhero.

And while all superhero tales require a suspension of disbelief, the idea that Superman can disguise himself as Clark just by putting on a tie and a pair of glasses. It even tested the patience of the people creating the comic. "The writing team and myself [were] a little tired of Lois not figuring it out," Mike Carlin, senior group editor of DC Comics, says in the 2006 documentary Look Up in the Sky! The Amazing Story of Superman. "It was starting to make her look a little stupid. And you can't be a top reporter and be stupid."

Elsewhere, the 1970s and 1980s were a good time for adolescent comic fans, defined by landmark series like Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen and Frank Miller's The Dark Knight, as well as Moore and David Lloyd's V For Vendetta. These were dark, violent, morally ambiguous, political stories that would melt the mind of any impressionable teenagerwho had long ago tired of Whizzer and Chips and Buster.

"It was the era of 'comics are for grown-ups'," Hibbert says. "So, there was always this idea that Superman was some daft, soppy, old-fashioned superhero who was just pointless and silly. And I think that was a very common opinion. It was the wrong opinion a very typical teenage opinion, which I think a lot of people have kept."

During the mid-1970s, sales figures of Superman titles had slumped to averages of 150,000 to 200,000 copies per issue. It was starting to look as if the best days of the world's most powerful superhero might be behind him.

Just in the nick of time, Superman: The Movie appeared. The idea of bringing the character to the big screen had been rumbling away since the 1940s. Now the film industry saw an opportunity to create a blockbuster with broad audience appeal—the success of fantasy films, advancements in special effects and growing interest in film franchises suggested this was the time.

After securing USD40 million in financing, DC's new owners Warner Brothers hired Marlon Brando to portray Jor-El, Superman's Kryptonian patriarch, for a record-breaking USD3.7 million, plus 11.3 per cent of the domestic gross and 5.6 per cent of the foreign gross. Casting Brando also helped secure Gene Hackman to play Lex Luthor for another USD2 million.

Then they went shopping for their leading man, in a search that was nothing if not thorough. Robert Redford, Paul Newman, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Clint Eastwood, Neil Diamond, Steve McQueen, Warren Beatty, David Soul and Burt Reynolds were all either considered then rejected or chose to pass.

"We were going completely nuts trying to cast the right guy," producer Ilya Salkind recalled. "We even tested the dentist of my first ex-wife."

In the end, director Richard Donner turned to the headshot of a 24-year-old Juilliard acting school graduate he'd rejected twice before, Christopher Reeve. He was so nervous during testing, there were sweat stains visible under his armpits.

The impact of Reeve's performance may have gone on to be enormous, but even he was unable to save Superman in the longer term. The failure of the fourth film in 1987 chimed with the comic's continuing decline on the newsstand. Even as Superman's 50th birthday was celebrated on the cover of Time magazine, the culture was going through a transformation again: thanks to Miller's aforementioned The Dark Knight and, in films, to Tim Burton's imaginative Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), the Caped Crusader was now the coolest crimefighter.

DC tried to offset the Man of Steel's ratings decline with eyeball-grabbing storylines. In Superman (Volume 2) #50 from December 1990, Clark Kent proposes to Lois Lane and she accepts. In Action Comics #662 the following year, he tells her his identity as Superman. But before the pair can walk down the aisle, the unimaginable happens.

In Superman (Volume 2) #75 from January 1993, a monstrous genetically engineered being from the depths of prehistoric Krypton known as Doomsday literally beats the life out of our hero. DC killed him off. The news, trailed weeks in advance, made global headlines.

"The Death of Superman" brought in USD30 million during its first day of sale and ultimately sold more than six million copies, doubling DC's market share.

The stunt made headlines around the world. And, of course, a stunt is what it was—after four proxy "Supermen" battled it out in the title over the following weeks, the original's body was eventually exhumed and healed using (what else?) Kryptonian technology.

One comic-book incarnation did show longer-term promise. The 12-issue All-Star Superman, written by Grant Morrison and drawn by Frank Quitely, which ran from 2005 to 2008, was praised as putting forward a “fresh and modern” Superman, with confident and emotionally intelligent storytelling that nonetheless paid homage to the character’s rich history (James Gunn has cited this particular series as a major influence on his new film).

Three years later, however, DC rebooted its entire comics inventory—“the New 52”—and Superman suffered/was saved from the ultimate ignominy, depending on your point of view. A costume makeover got rid of the red “underpants”, giving him a new look: one that consisted of jeans and a T-shirt with an “S” logo. “Once again, DC Comics decided that it knew why its heroes weren’t appealing to readers outside the increasingly shrinking audience of hardcore fans,” notes Glen Waldon sarcastically, in his 2013 book Superman: The Unauthorised Biography. “They weren’t accessible.”

Waldon highlights another standalone book from the same time, Superman: Earth One, with “a 20-year-old Clark Kent, sporting a hoodie, low-cut jeans and a Justin Bieber bob”. Outlet after outlet took the “They’re Changing Superman into a Hipster!” bait. Many seized on the opportunity to make hacky hipster jokes, such as “Will the Fortress of Solitude become a Williamsburg co-op?”

On a more cerebral tip, Superman even announced his intention to address the UN and renounce his US citizenship, in a move that drew fire from presidential candidate Mike Huckabee. “I’m tired of having my actions construed as instruments of US policy. ‘Truth, Justice and the American Way’—it’s not enough any more,” the character announced. “The world’s too small. Too connected.”

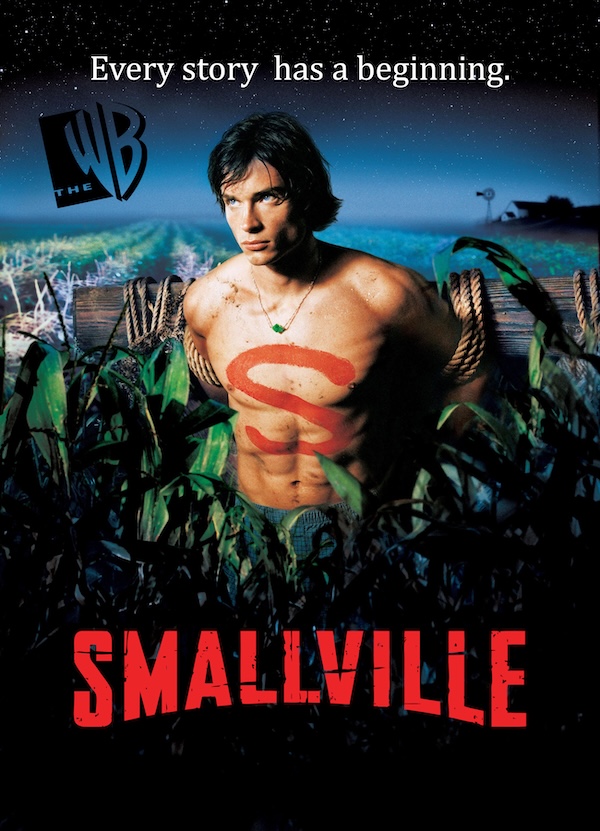

While the comic books went through multiple identity crises, Superman did at least triumph on the small screen, via two hit TV shows. Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, a romantic comedy version with Dean Cain in the title role, ran for four seasons between 1993 and 1997. Smallville, the coming-of-age tale of a teenage Clark Kent before he becomes his alter ego, played by Tom Welling, with a strict “no tights, no fights” rule, ran for 10 seasons between 2001 and 2011. Smallville was also notable for a guest appearance from Reeve, tragically paralysed from the neck down in a riding accident in 1995, playing Dr Virgil Swann, a reclusive scientist who helps Kent understand his Kryptonian origins.

Comics Reddit still laments the Superman film that never was from that era—Superman Lives, cancelled three weeks before filming was set to start in 1996 with director Tim Burton and star Nicolas Cage. In 2008, Marvel began building its Cinematic Universe, with the release of Iron Man. This year’s Thunderbolts* will be the 36th film from the MCU. Why has Marvel succeeded where DC has stumbled?

Partly, says Dr Mark Hibbert, because it took its time with its world-building, closer to the Lee-Kirby-Ditko model. “They started with one really good Iron Man film, and then another not quite so good Iron Man film,” he says. “But then there was a really good Captain America film. You have to have those really good films to start with, and then you can bring them together.”

Tom Oldham is the manager of Gosh! Comics in London and, as you might expect of a manager of any comic-book store anywhere, is something of an expert. He is also no big fan of superhero films. He reasons that they tend to be “an advertisement for an IP franchise”. Yet even he sounds cautiously optimistic about James Gunn’s upcoming take.

“Obviously it’s nice to have a change in vibe, compared to the miserable Snyder-verse,” he says. “The weirder the better, hopefully. And stories that are a bit more hopeful can still have artistic merit. It’s why the most cherished versions of the character are All-Star Superman and the first Christopher Reeve films.”

Another potential obstacle Gunn faces is that the avatar that once stood for American exceptionalism is appearing at a time when a real-life Lex Luthor seems to be running the show. “Neither Truth nor Justice do appear to be the American Way, do they?” says Hibbert. “It’s like [Superman villain] Darkseid is in charge of everything and the [evil cosmic formula used to control all existence] Anti-Life Equation is sacking health workers across the country.”

“It’s not ideal that, as North America descends into open fascism and open oligarchy, we have this potentially pro-United States totem,” agrees Oldham. “But I don’t think that’s ever not been the case: that the American empire shouldn’t be telling the rest of the world what to do, whether it’s through a superpowered avatar or otherwise. So let’s wait and see the film. You can also create quite powerful political critiques through totems like Superman. I mean, I doubt that’s going to happen, but let’s see.”

Perhaps, in light of America’s currently tarnished international reputation, the new film’s timing may actually prove important. Superman has been described, after all, as the ultimate American immigrant: an alien from outer space who comes to save Earth, rather than defeat it. In the comics, his moral crusade has seen him take on real-life villains of the Far Right, from the Nazis to the Ku Klux Klan.

“The great fiction of Superman is ‘What if someone had all this power but used it for good?’” Hibbert says. “You know, that’s quite relevant now. All that lovely stuff that Christopher Reeve really did embody—he was like Superdad. Well, if we can have a bit of that back again, I think it’ll be lovely. That’ll be a salve for everybody, where you can go ‘Thank goodness Superman’s here’.”

Hibbert likens his own superhero journey to a maturing appreciation of The Beatles.

“Usually, you start reading comics when you’re about six or seven,” he says. “And you go ‘Oh, wow, Superman. He’s brilliant. He’s going to do all this stuff.’ And then you get to 11 or 12 and suddenly Batman becomes the cool one, he’s fighting all these people… It’s like the adage where you start off being a fan of Paul, then you become a teenager and you become a fan of John. And then, in later life, when you get to middle age, you go ‘Ringo was the best, obviously.’ And I think it’s the same with Superman. You go ‘Well, this kind of goofy, fun guy—that’s the one we want.’”

He’s hopeful, too, that this could finally be the break DC has been looking for. “Superman is an amazing idea,” Hibbert says. “He really is immortal. He will live longer than any of us. It takes really talented people to write good, interesting stories that make you sympathise with an invincible character like Superman. James Gunn has shown he’s really good at doing this mix of stupid, grown-up humour, with a kind of hope. I think we’re going to have a lovely, friendly Superman. And a lovely, friendly dog.”

“Ultimately, superhero films should be a bit silly,” agrees Oldham. “So, give us stupid super-powered dogs flying around. Because, why not?

Superman is now in theatres.

Originally published in Esquire UK Summer 2025 issue