Our goal is to become activists. We must rely on our own actions more than on words. And these are just words.

Can Dune change the world? Can a novel that involves old-timey knife fights and giant space worms convince people to get serious about climate change? Is it possible the book could encourage more religious tolerance and understanding? Cautiously, the answer to these questions might be yes. Because although Dune did not truly begin its life as a political or ecological text, it’s impossible to ignore those themes in it today. Between 1965 and now, Dune transformed from a curious science fiction book released by an automotive repair manual publisher to a book that seemed to be a repair manual for the entire planet.

On April 22, 1970, in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, Frank Herbert spoke to thirty thousand people in celebration of the very first Earth Day. He told the gathered crowd he wanted everyone there to “begin a love affair with our planet,” and to that end, he hoped that they would all join him in never again buying a new car. He firmly believed that if people boycotted the purchase of new internal combustion engines, the automotive industry would eventually be forced to make more efficient cars or create clean-energy fuel alternatives. “Getting rid of internal combustion will be no permanent solution," he said. "But it will give us breathing room.”

At the time, Herbert was also concerned about overpopulation as well as pollution. Some of the ways he phrased his arguments may seem dated. But it’s also striking how mainstream most of his views are today. The public perception of Dune as an ecological science fiction novel is perhaps the most important factor in its immortality. And while Herbert himself was a bit preachy, his novel isn’t. And that’s how the magic happens.

Herbert’s self-styling as an environmental activist didn’t happen in 1965 when the hardcover was published by Chilton, and it didn’t happen in 1966 when the first paperback version was published by Ace. Instead, the public transformation of Dune from an underground science fiction novel to an essential ecological text read and analyzed by environmental activists happened in 1968, three full years after the book hit bookshelves.

“I refuse to be put in the position of telling my grandchildren: ‘Sorry, there’s no more world for you. We used it all up,’” Frank Herbert said in 1970, in the nonfiction book New World or No World. “It was for this reason that I wrote in the mid-sixties what I hoped would be an environmental awareness handbook. The book is called Dune, a title chosen with the deliberate intent that it echo the sound of ‘doom.’”

I refuse to be put in the position of telling my grandchildren: 'Sorry, there's no more world for you. We used it all up.'"

The notion that Herbert wrote Dune specifically because he hoped it would be an “environmental awareness handbook” is almost certainly revisionist. But that doesn’t make Dune’s political and environmental commentary incorrect. Even the earliest versions of “Dune World” contain ecological themes simply because of the way Arrakis works. Herbert later said that on Arrakis, both water and spice are analogues for oil, and of course, for “water itself.” The idea that Arrakis wasn’t always a desert wasteland is suggested vaguely in the first novel, but what Herbert’s later novels—specifically 1976’s Children of Dune—do is to reveal a kind of inverted problem. Because of the rapidity of forced climate change on Arrakis, the most integral part of the wildlife—the sandworms—is pushed to near extinction. What is subtle in the first novel is made perfectly clear in the sequels.

Herbert even tips his hand to his own revisionism because he mentions Pardot Kynes—a character you’re excused from forgetting because this person doesn’t really appear in the actual story of Dune. Most of Pardot’s story and his quotes come from the first appendix in Dune, “The Ecology of Dune,” which gives us the backstory of Pardot Kynes, the father of Liet-Kynes, the imperial planetologist who more famously accompanies Leto, Paul, and Gurney during their first inspection of the spice mining and later gives his life to save Paul and Jessica in the desert. As Liet-Kynes lies dying, he recalls a quote from his father: “The highest function of ecology is the understanding of consequences.”

"The highest function of ecology is the understanding of consequences."

“I put these words into his mouth,” Herbert said in 1970, speaking of both Liet-Kynes and Liet’s father, Pardot.

Because the science fiction community inconsistently embraced Herbert in the late sixties, he found his true community with environmentalists. In 1968, within the pages of The Whole Earth Catalog, biologist and editor Stewart Brand forever changed the perception and importance of Dune. The Whole Earth Catalog was a publication conceived by Brand as a way of giving forward-thinking environmentalists and progressives “access to tools” for rethinking everything about the way humankind saw Earth. In the introduction to the first catalog, Brand wrote that hardships caused “by government and big businesses” led to a movement where “a realm of personal power is developing—power of the individual to conduct his own education.” To that end, Brand created The Whole Earth Catalog with the following stated purpose: “The Whole Earth Catalog functions as an evaluation and access device. With it, the user should know better what is worth getting and where and how to do the getting.”

On page 43 of this catalogue, Dune was listed with the following description: “A more recent Hugo Award winner than Stranger in a Strange Land, is rich, re-readable fantasy with a clear portrayal of the fierce environment it takes to cohere a community. It’s been enjoying currency in Berkeley and saltier communities such as Libre. The metaphor is ecology. The theme revolution.”

One of Brand’s big criteria for anything listed in The Whole Earth Catalog was that it could “not already [be] common knowledge.” By 1970, when Frank Herbert was invited to speak at the first Earth Day, it’s safe to say that Dune’s ecological themes were common knowledge. But in 1968, that hadn’t happened yet. These two years rewrote the reputation of Dune, for the better. And this seemingly influenced Herbert to take his sequels in directions more in line with his ecological views and less aligned with what a smaller science fiction readership might have wanted.

"The metaphor is ecology. The theme revolution."

In crafting the first Dune, Herbert created a science fiction novel that was palatable to old-school science fiction readers while attempting something new: establishing world-building that had far-reaching implications about the environmental struggle of our own planet. Herbert may not have sold Dune to Analog or Chilton or Ace as an ecological book, but once prominent environmentalists picked up on what he was laying down, his true colours were shown. It’s tricky to believe that Herbert really picked the title Dune because it reflected the word doom, mostly because the process through which he started writing the book doesn’t seem to support that. But, even later in his life, Herbert seemed to walk the environmentalist’s walk that he outlined in New World or No World.

A decade and a half after the publication of this book, both his son Brian and his widow, Theresa Shackleford, confirmed that Frank Herbert loved riding around in limos and always flew first class if he could help it. And yet, by all accounts, he never broke his promise in 1970. To his dying day, Frank Herbert never, not once, bought a new car.

But if the environmental legacy of Dune is clear, its political messaging is less on-the-nose. For various critics and scholars, the political messages of Dune are not all one way. Is it a story that elevates minorities and, along with the Fremen, truly punches up?

In 1984, Francesca Annis, who played Lady Jessica in the David Lynch Dune, said that she read the entire story of Dune in a conservative light. “I can’t relate to the story politically,” she said. “The book just doesn’t say much about ordinary people. As far as its values are concerned, it’s just one group of powerful people triumphing over other powerful people. In that way, it’s a very right-wing story.”

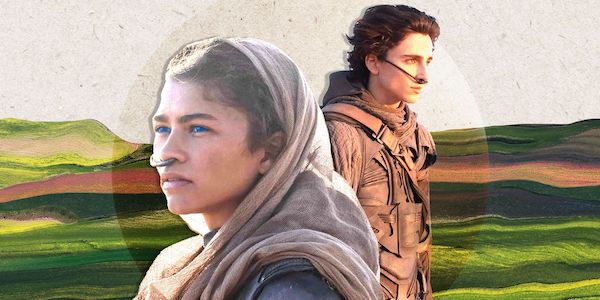

You can kind of squint and see where Annis is coming from, especially through the lens of the 1984 film. Close readings of Dune reveal the subversion Frank Herbert inserted into this “white saviour narrative,” and as prominent Dune scholar Haris Durrani has pointed out, even in his subversion of it, Herbert still “reinscribes the white saviour narrative.” From this point of view, Paul and his family are like missionaries, coming to “tame” a native people, steal their culture via Bene Gesserit manipulation, and then create a new power base that is arguably just as bad, if not worse. Again, as Zendaya’s Chani says at the beginning of the 2021 film, “Who will our new oppressors be?”

Without change, something sleeps inside us and seldom awakens. The sleeper must awaken.

“If Herbert wanted to make it clear that he was subverting the hero’s journey in the first novel, he could have done a better job,” historian Alec Nevala-Lee tells me. “It’s clearer in Messiah, but it’s easy to read the first novel the ‘wrong’ way.” But Durrani isn’t so sure. For him, Dune isn’t a white saviour narrative at all and is somewhat secretly a one-of-a-kind twentieth-century science fiction novel that speaks to Muslim ideas.

“It’s an attempt to explore Muslim ideas and different Muslim cultures in a way that I think is unique,” Durrani tells me. “There was something unique about what Herbert was doing, bringing his unique viewpoint to thinking about the future of Islam and other Muslim cultures.” The evidence Durrani cites relative to the Muslimness of Dune is somewhat obvious for any reader with an Arabic or Muslim background. In the first book, Paul is sometimes referred to as “the Mahdi,” which in Arabic refers to a spiritual leader who will unify and save the people, generally just before the entire world ends. For Durrani, this idea blurs the “white saviour trope,” because you can easily imagine a version of Paul who isn’t white but is still a fallible and dangerous leader.

“Is he white?” Durrani says with a laugh. “I mean, you could imagine a version of Paul who wasn’t white. I certainly think Gurney Halleck is a nonwhite character. Herbert probably intended Paul to be white, but he’s also drawing on histories of North Africa and the reference to the ‘Mahdi,’ who is not white. I think what’s interesting is that even if Paul is a nonwhite character, he’s still a colonial character. Herbert is playing with ideas of internal colonisation.”

As Durrani outlines in his essay “Dune’s Not a White Saviour Narrative. But It’s Complicated,” the agency of the indigenous people of Arrakis (the Fremen) “appears downplayed,” mostly because of “the narrative focus on the Atreides and Bene Gesserit.” But, from his reading of the text and Herbert’s various comments over the years, Durrani says that all the colonist themes in Dune are strictly anti-colonist, even when the “heroes” are depicted as such. “I read the focus on leaders as critical, not hagiographical... Herbert saw the series as about communities, not individuals.” While talking to me in 2022, Durrani tells me that the endpoint of the series, in Chapterhouse: Dune, features a slate of heroes and protagonists who are specifically not the pseudo–Anglo-Christian characters of House Atreides in the first book. “I think it is significant that the whole series ends with basically a rabbi, a Fremen, a Sufi saint, and basically some guy who’s representative of Afghanistan,” Durrani says. “I don’t know if Herbert was successful, but he wanted to do both: You could read this as just a traditional sci-fi story of this heroic journey. And he wanted the sense of people who are playing into that narrative. But it’s a hard line to walk.”

Dune may or may not convincingly subvert the white saviour tropes, but it does push back against other clichés in coming-of-age stories and hero’s journeys. Nobody refuses the call to adventure in Dune. And Paul’s parents aren’t distant and mythical like nearly all the parents in Star Wars. In fact, the story of the first Dune is as much the story of a mother as it is of a son. Imagine Luke Skywalker growing up with Padmé guiding him, while also fighting her own battles, and you’ve got an approximate feeling of just how radical Dune is within the pantheon of other sci-fi adventure epics. Even Leto II’s transformation into the God Emperor isn’t a black-and-white Darth Vader morality tale. Dune doesn’t wag its finger at bad decisions. It reminds us that everything has consequences.

"Dune doesn't wag its finger at bad decisions. It reminds us that everything has consequences."

“Herbert thought of science fiction... as a form of myth,” biographer William F. Touponce wrote in 1988. “But he did not see myth as an absolute. Myth and Jungian archetypes were simply another discourse that he set out to master and that he incorporated into the dialogical open-endedness of his Dune series.”

Now, contrast this kind of thinking with Star Wars. Everyone is told over and over that the reason that saga is so popular is that George Lucas stuck so close to the archetypes that people couldn’t help but love it. Dune is the opposite of Star Wars in this way; Herbert uses archetypes like the “hero’s journey” as what Touponce calls a “strategy” to “get people emotionally involved in his stories.” Touponce points out that with the publication of Messiah and Children of Dune, some more traditional, Campbell-era SF readers felt like Herbert had betrayed them. And maybe he had. Whether it was slightly retroactive or not, Herbert used the hero’s journey as a framework, but unlike Lucas, he didn’t adhere to it. Dune rejects the archetypes it creates, which gives the story more flexibility. This is why the saga continues to organically expand well beyond what Herbert wrote.

After Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two is out on home video and streaming sometime after spring 2024, the immediate future of Dune is the Bene Gesserit. Created by Diane Ademu-John along with showrunner Alison Schapker, the forthcoming HBO TV series Dune: The Sisterhood will tell the story of the origin of the Bene Gesserit roughly ten thousand years before the events of the first novel. This series is loosely based on Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson’s 2011 novel The Sisterhood of Dune, which charts the rise of various organisations in the Dune-iverse, including the Spacing Guild and the human computers known as the Mentats. As the 2020s march on, the future legacy of Dune will possibly leave the story of Paul Atreides on Arrakis in the dust. Although there is a huge degree of uncertainty around the future of the Sisterhood series, one stated premise would follow two sisters, Valya Harkonnen and Tula Harkonnen, as they struggle to establish the Bene Gesserit order amid the reign of Empress Natalya.

The last name of the two protagonists—Harkonnen—should raise some eyebrows, too. In the distant past, the dreaded enemy of House Atreides wasn’t necessarily all evil, demonstrating that the unfolding story of Dune continues to defy easy classification. The idea of a sci-fi prequel series revealing its two main characters are part of a family that has largely been portrayed as villains would be like if there was ever a Sherlock Holmes prequel set in the 1400s, in which a heroic captain named Moriarty battled for truth and justice on the high seas. The specific place that Dune: The Sisterhood will hold in the long history of the flowing spice is, at this time, unknowable. But its basic setup has the potential to make The Sisterhood the most transgressive Dune story yet, and if the show enjoys Game of Thrones–level enthusiasm, push the chronicles of Arrakis even further into the mainstream.

The timing of Dune’s twenty-first-century renaissance isn’t just a coincidence. It’s true that Dune has benefited from the gradual mainstreaming of sci-fi and fantasy in the early twenty-first century, but because the phenomenon of these novels and books has always stood separate and apart from sci-fi trends, the emergence of Dune as a dominant pop culture force now is explicable for bigger reasons. In New World or No World, Herbert equated apathy regarding environmental activism with trying to rouse a “heavy sleeper.” But he also believed that people could change: “We can shake the sleepers—gently and persistently, saying ‘time to get up.’”

The history of Dune’s making is a history of contradictions and paradoxes. And, crucially, how we can emerge from that chaos better and wiser. In a lovely and famous Dune scene, Duke Leto tells Paul that “without change, something sleeps inside us and seldom awakens. The sleeper must awaken.” Although often attributed to Herbert’s book, these exact lines comes from the 1984 film, not the novel version of Dune, proving that interpretations and, yes, revisions of Dune have the power to reshape our thinking and our hearts.

"The history of Dune's making is a history of contradictions and paradoxes."

Later, in both the 1984 Dune and the novel, Paul speaks of his awakening, when he becomes the person he believes he’s meant to be. Dune’s meaning to millions and its longevity are specifically connected to this kind of thinking: We can ignore the ills of the world, but not forever. At some point, everyone will have to wake up. On the final page of New World or No World, Herbert writes a single question, wondering if all the storytelling and real talk are sinking in. He asks damningly, and quite simply: “What are you doing?”

The “what” he refers to is somewhat obvious. Are you actively doing something positive in your community? Are you acting generously? Are you doing something about the horrible power structures that keep people down? Herbert may have found his fame and fortune through Dune, but his creation endures not because it lets us escape and ride a sandworm and get super-high on an awesome space drug, but because it makes us feel guilty.

From racial and gender inequity, to class divide and poverty, to dishonesty and corruption in politics, Herbert believed that communities can turn back the slow tide of oppression. The hyperbole in Dune helps to illustrate the ways in which those revolts might happen and the ways in which those revolts might go wrong. Misinformation motivates many of the horrible events throughout Dune, especially when ideological demagogues allow their followers (or voters) to believe they are above the law.

From the real sand dunes of Oregon to the spice fields of Arrakis, Frank Herbert’s heart was always in the right place. His intentions don’t mean that Dune is perfect or without problematic elements. And yet, unlike so many touchstones of twentieth-century literature, Dune is unique because its weaknesses are also its strengths. It’s a story that dares to make us hate the heroes and search inside ourselves for ways in which we, too, have made the same well-meaning mistakes. It challenges us to think outside of our own day-to-day experiences and imagine a world in which just one drop of water is more precious than gold. It pushes us to rethink our emotional strategies in dealing with disappointment, failure, and most of all, fear.

As Paul’s mother teaches him, the Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear is the first and last line of mental defence. The battles fought in Dune occur across various planets and employ all sorts of ingenious weapons. And yet, throughout all the book, film, and television Dunes, the internal human struggle not to give in to fear is paramount. We know that honorary Bene Gesserit Yoda correctly linked fear with all sorts of other horrible outcomes, but Star Wars suggested that a connection with a magical energy field was required to beat back that fear. The Bene Gesserit teach that the battle can be won within your own mind. Tamping down fear doesn’t work. Ignoring it or allowing it to morph into rage can lead to “total obliteration.”

Instead, all of us, every day, have to face our fear. In the world of the twenty-first century, the growing number of fears is seemingly greater and more relentless than ever before. The mental health of each person in the world is like a dam holding back the tide of chaos. And Dune helps. A little. As Herbert said in 1970, “these are only words,” but he also taught us that fear truly is the mind-killer and that the battle for a better world begins inside each person.

“In horrible times, people tend to turn to musicals or science fiction,” Rebecca Ferguson, Lady Jessica herself, tells me. “Personally, I think the world of Dune is so profound and so layered that I hope it’s the kind of thing more of us can turn to. If people do need to escape, do need to feel comfort, I think this brand of science fiction, this kind of reflective art, is buoying and transformative. I hope it helps people. I truly do.”

Ferguson didn’t need to use the Voice to make this ring true. The love of Dune in all its forms is about both things: escape from fear and awakening from a slumber of the mind.

Dune allows us to live in the future, love the artistic intricacy of that future, and then realise, with sobering clarity, that we can’t allow things to end up like that. Dune teaches us to face our fears, to recognise there are plans within plans, and to accept that not every victory is always what it seems. It also makes us look in the mirror and wonder who we are. Like Alia, Leto, and Ghanima, it sometimes feels as though we all have the memories of our ancestors lurking in our minds. The horrible things we’ve done as a species as well as the triumphs are all there, running through our minds at the same time. Dune says there is no way to turn away from the mixed bag of human history. There’s no easy fix for the horrible ways history has unfolded or the ways in which it may repeat itself. Herbert ended his last novel, Chapterhouse: Dune, with a leap into an unknown part of space, a future that was suddenly unwritten. “We’re in an unidentifiable ship in an unidentifiable universe,” Duncan Idaho says. “Isn’t that what we wanted?”

The mystery of the future of humanity is similar. We can’t yet imagine the way in which we get to the future, and we can’t really picture what the universe will look like when the future unfolds. But it is what we want: to survive and to change. Dune says that change is possible. It’s not always all good, but it’s not all bad, either. “The best thing humans have going for them is each other,” Frank Herbert said. We don’t have to be owned by our fear. Because in the end, we can look at ourselves honestly, at this moment, and ask, without fear, “What are you doing?”

From THE SPICE MUST FLOW: The Story of Dune, from Cult Novels to Visionary Sci-Fi Movies by Ryan Britt.