The word for this issue’s column is “patina.” I picked it after seeing the coffee shop uncle scrapping the charred parts off the kaya toast I ordered, and I thought about someone meticulously sanding the character out of a perfectly good wooden table, trying to restore it to some imagined original state. The irony was thick enough to spread on toast.

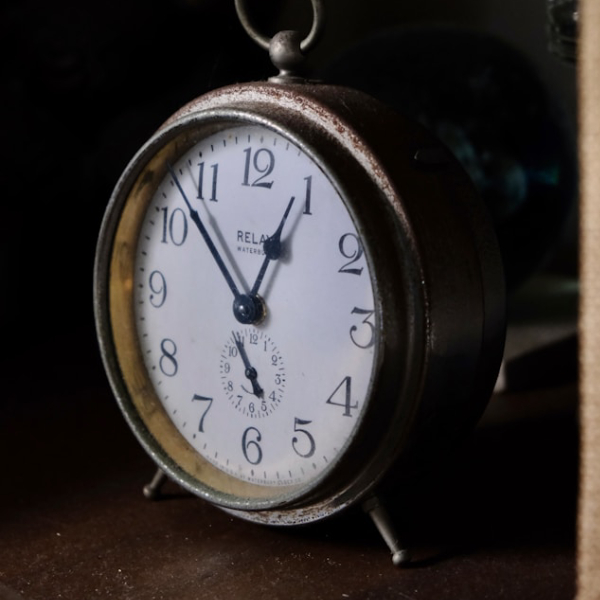

Like most beautiful concepts, it has grown beyond its etymological boundaries. Patina is what happens when time collaborates with matter, when use becomes art, when the ordinary accumulates extraordinary character through the simple act of existing.

Walk through any neighbourhood built in the past, and you’ll see patina everywhere. Brick walls where ivy has painted abstract murals in chlorophyll. Wooden doorframes polished to silk by countless hands. Stone steps worn into gentle depressions by generations of footfalls, each one a vote for this particular path through the world.

Now walk through a new development, where everything gleams with the desperate perfection of things trying too hard to look important. The faux-aged beams that fool no one; the pre-distressed furniture screams its artifice. Take a gander at the weathered signs that emerged from a factory last Tuesday. It’s like watching someone practice their laugh in a mirror.

You can buy jeans that arrive pre-faded, guitars that come “road-worn,” leather jackets that have been tumbled with rocks to simulate lives they’ve never lived. The market for artificial patina is worth billions, which tells you everything about what we’ve lost and how desperately we want it back.

The manufacturers of instant character miss something fundamental: patina isn’t just about appearance. It’s about the accumulation of experience. That green oxidation on copper is a chemical diary of every rainstorm, every touch, every breath of salt air that surface has encountered.

The patina knows things. Cast iron skillets passed down through families develop cooking surfaces that are black mirror-smooth, seasoned by thousands of meals into something magical. No amount of money could buy what those skillets know about cooking, because that knowledge lives in the accumulated layers of use.

The Japanese understand this with their concept of wabi-sabi: the beauty of imperfection and impermanence. They see that the crack in the tea bowl as a feature; that the asymmetrical rock in the garden tells a story about surviving earthquakes. They know that trying to preserve things in perfect condition misses the point entirely. The most interesting people wear their patina openly. Writers whose laugh lines map decades of finding things funny. Musicians whose guitars beart he ghost impressions of countless songs. Bartenders whose hands move with the muscle memory of ten thousand perfect pours.

Relationships develop patina. New love is all sharp edges and perfect angles, everyone maintaining the illusion of flawless compatibility. Couples who’ve been together for decades have developed the easy wear patterns of people who know each other’s rhythms. Their conversation have the comfortable inefficiency of paths worn between two familiar points.

Cities with patina understand something that planned communities never will. Paris municipality accrued centuries of people making the best decisions they could with what they had. The result is an organic complexity that no urban planner could replicate through PowerPoint presentations. Professional patina-makers exist, artisans who can age new copper to look centuries old, antiquers who can make pine furniture appear to have weathered colonial winters. Their craft is honest when acknowledged as craft.

This is why we’re drawn to vintage everything: the reassurance that somethings were built to last, built to improve with use rather than degrade. In a world of planned obsolescence, patina represents hope. Proof that some things get better with time, that wear can be a form of worship, that imperfection can be a kind of perfection.

Antique brass develops that particular green-black complexion that speaks of decades spent in pockets, of fingers that knew its weight and texture. The patina carries the accumulated intention of everyone who found it worth keeping, worth using, worth passing down. Modern manufacturing tries to replicate these effects in weeks that nature accomplishes over decades. Chemical treatments can approximate the visual results.

There’s something in authentic patina that resists simulation, a complexity that emerges from experience rather than intended effect. The patina on old leather tells you about the person who wore it, how they moved, where they went, and what season they encountered. Each scuff and fade are evidence of a life lived rather than a life performed.

This is information that no amount of artificial aging can encode. What patina represents is accumulated intention: the visible evidence of caring enough to use something until it becomes irreplaceable. In a disposable world, it’s the closest thing we have to permanence. Sometimes the most radical act you can do is simply let things age gracefully.