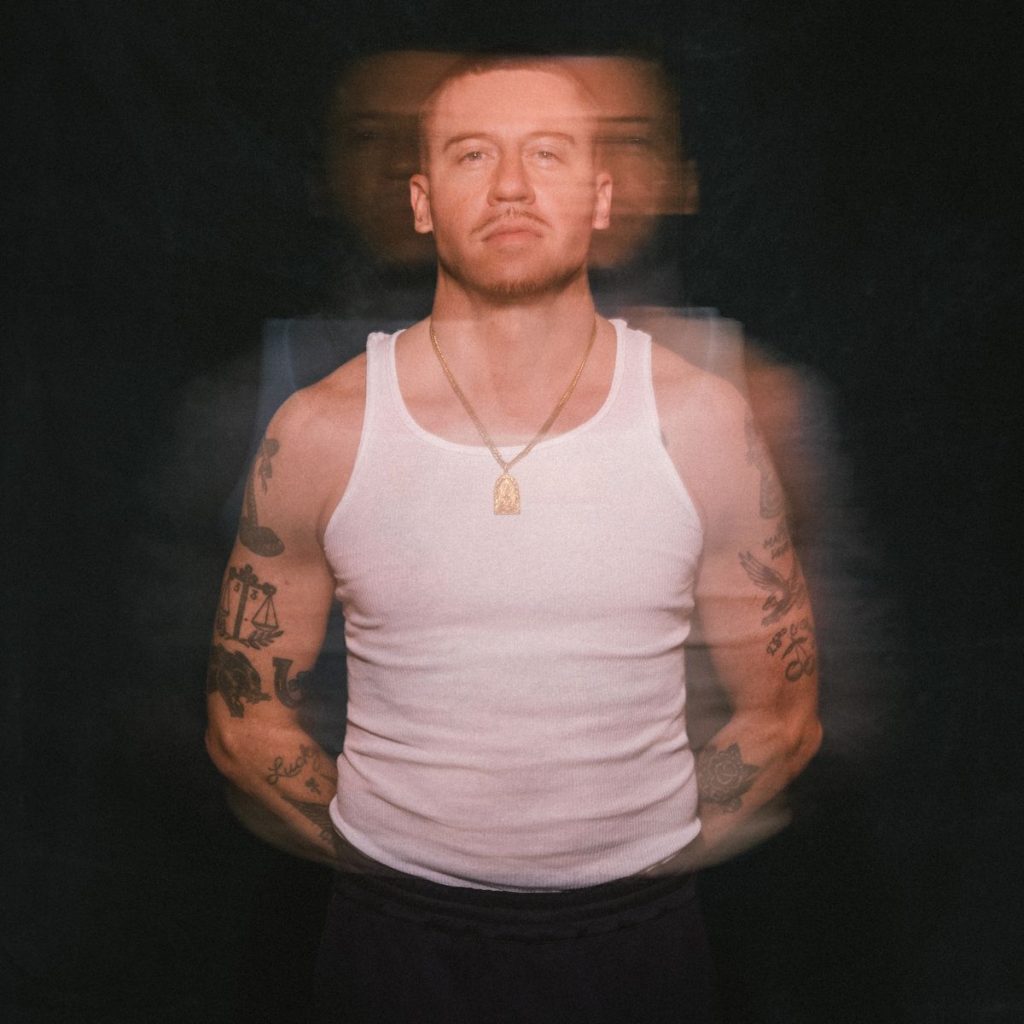

Macklemore descends a dark stairwell into the downstairs lounge of a Midtown hotel, where I’ve set up shop. It’s raining outside, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at him. Dressed in his clothing line, Bogey Boys, he sports a yellow shirt and an even brighter grin. “Hi,” he says, offering a stiff handshake. “I’m Ben.” In three days, Macklemore’s third solo album, Ben, will drop—and the 39-year-old rapper is running around New York City to promote it.

His schedule looks something like this: hop off a cross-country flight, meet up with me, and head to 30 Rock to perform on The Tonight Show. We're talking about his upcoming Jimmy Fallon spot when an intrusive thought comes to my mind. “Wait,” I wonder aloud. “What does Macklemore mean?” He answers my question with a shy laugh. “Oh man,” he says, taking a hit from his vape.

Macklemore came up with the name when he was 17, attending the Pratt Institute for a summer arts program. Back then, he spent most of his time wearing thrifted plaid outfits and sneaking sips of malt liquor. “I would call myself Professor Macklemore,” he explains. “Eventually, I had to come up with a rap name. I dropped the professor and Macklemore stuck. The rest is history.” Fast-forward about a decade and Macklemore—pardon me, Ben—releases “Thrift Shop,” with Ryan Lewis, his former collaborator and producer. The wacky rap about popping tags went viral (the music video has 1.7 billion views and counting) and suddenly, the hip-hop hopeful who'd been plugging away for well over a decade was a sensation. After “Thrift Shop,” came the equally popular single “Can’t Hold Us,” and four Grammys. Most notably, the duo won Best Rap Album for The Heist, which beat Kendrick Lamar’s good kid mA.A.d city.

Macklemore was more concerned with the fanfare back in the “Thrift Shop” days, but now his priorities have changed. Kids will do that. I ask if his children like his music. “[My four-year-old daughter] Coco has really sensitive ears,” he says. “If I’m gonna bump my own music, I’m going to slap it. So, she’s not into it. We’ve had many fights in the car.” Meanwhile, his one-year-old son, Hugo, appreciates the craft. “He’s got this bop to him. It’s on beat, goes back and forth, so he’s riding with me,” the rapper says. And his oldest? Well, she’s his number-one fan. Sloane, who’s just seven years old, directed his new music video for “No Bad Days,” a saccharine track from his new record.

The music video for “No Bad Days” is out now, along with the rest of the album. To celebrate, Macklemore spoke with Esquire about the "Thrift Shop" era of his career, working with his daughter, and a brief relapse that may have changed the course of Ben.

ESQUIRE: Did Ben turn out as you originally planned, or has its shape changed over time?

MACKLEMORE: No, we had a pandemic right at the tail end of when we thought we were going to put it out. So, the plans completely shifted. We had to scramble and realize that there was nothing that we could do. We weren't able to tour, and it's always been the way that I've connected with the art. Being in the studio can be isolating. I go into a room, write, and try to extract and exfoliate the spirit and see what comes. This was one of those moments where I knew that I didn't want to put out anything without being able to experience it with the people that bring the art to life. Because it's one thing in the studio. It's another thing when people are singing the music back to you. That feels like a full-circle moment. Without that, I don't think that this chapter would've felt closed.

Why did you name the album Ben?

This album felt like a reminder of where I'm from. A reminder of what has created the stories that make me who I am. Every album is an opportunity to strip away layers, to get closer to the heart—the thing that I'm trying to connect to every time I'm in the studio... Ben felt fitting. My parents named me Benjamin. I’ve been Ben my entire life. Shedding our masks, getting away from the boxes that society puts on us, and getting back to that core glue of what makes me a human—let's write from that place.

I’m not trying to fit into the box of what is contemporary. I don’t want to fit into a box, period.

Ben was partially inspired by a relapse you experienced after being sober for nearly two years. Tell me about that.

Of course. COVID happens and my world shifted really quickly—like everyone else’s did. My world looked like consistent 12-step meetings, in-person, and those stopped. The Zoom meetings that had replaced in-person meetings started. Eventually, I stopped prioritizing my recovery. From the beginning of COVID—this is something I haven’t talked about—my disease was screaming at me. It was like, The world is stopped right now. You have this imposed break where you’re in limbo, where nothing really matters, where all of a sudden you’re at home with your kids, with nothing to do. Get high.

That voice had gotten louder and louder, so finally I listened to it. Luckily, it was only a couple weeks. It could have been worse, but it was still really painful. I don’t know how much of the album it shifted. When you go through an experience like that where you’re rebuilding who you are, rebuilding your marriage, rebuilding trust—there’s a lot to write about. There was a lot of pain to pull from. I think that records like “Sorry,” and records like “Faithful” are two that probably have a direct correlation to that relapse.

My favorite song from Ben is “No Bad Days.” You asked your daughter, Sloane, to direct the video. What was that experience like?

I love working with Sloane. Just seeing her mind work and giving her the autonomy to make decisions as a seven-year-old. And they’re great decisions! I’m like, Yo, why am I paying all these people over here? Like, that’s actually the truth that just came from a seven-year-old. This will be a moment that we're able to look back on for the rest of our lives. It was something special. The actual creation process is not our issue—our issue is the attachment to the outcome. As long as I’m working with my daughter, it’s not about views, it’s not about likes, it’s not about the algorithm. In fact, we don't even pay attention to that. What we pay attention to is is the process of making the best piece of art.

Let’s talk about “Heroes.” It speaks to your upbringing in Seattle and fascination with rap culture. Who introduced you to that?

So I had a next-door neighbor named Andy Munt, who has since passed away. I was walking around the day before yesterday with my wife, thinking how my life would've changed if it wasn't for Andy introducing me to gangster rap at the age of seven. That changed everything. He loved gangster rap and that's what I first fell in love with—outside of the Beverly Hills Cop soundtrack and Michael Jackson. It was followed by gangster rap, early on. I fell in love and I never stopped.

Do you remember what artists you listened to back then?

I remember bumping NWA. As a seven-year-old, I was like, I can’t believe they’re saying this.

Have you had the chance to meet some of your other favorite rappers?

Each one is different. The ones that stand out to me are JAY-Z and Kanye. When I first met both of them, it was amazing to feel validated by people you have grown up listening to. That you have studied. When your life has been shaped by the art that they’ve made, to have an interaction around your art, it’s a very validating feeling. And to get that love and excitement from those guys, the first time I met them, was something I’ll never forget.

Have you ever felt like an outsider in the rap community?

In terms of my own identity, my own place, my own sense of self? No. In terms of how the music I make, and being able to fit that into a box—there have been times where it’s like, Well, this doesn’t necessarily add up with what’s contemporary right now. Even with songs on the album, you couldn’t take one of those songs and necessarily put it on like one of the hip-hop playlists of today or RapCaviar, you know. I’m not trying to fit into the box of what is contemporary. I don’t want to fit into a box, period. Now, if I happen to create something that’s contemporary, then that’s just what was felt that day. But I never want to reroute natural artistic inclination to match what’s going on in contemporary culture.

Do you think people assumed you’d be a one-hit wonder after “Thrift Shop?”

Of course. Any time that you have a record by anyone that's that big, there's going to be a, Oh, this is gonna be a one and done.

Did you feel like you needed to prove yourself?

The biggest proof was following that up with “Can't Hold Us.” Another number one. After that though, there's never like an Okay, now I've achieved this and this—I've checked these two boxes. I still want to compete. It's not that I necessarily want another number one, it's that I still want the art to have meaning. After The Heist had such success, and then our sophomore album, and This Unruly Mess not living up to that same level of commercial success... Gemini was really important to me, with “Glorious,” “Good Old Day,” and “Marmalade.”

As long as you're making good art, it's gonna find the people that it's supposed to find. There's this feeling of being a puppet master. Like, If we just get this feature, and get put on this playlist, then we get the Times Square billboard. That's not what this shit is all about to me. It's really not. It can become that if we talk too much about it, but that's what Ben is about. That's what this album is about. I have had diamond records and been miserable. I have had records that have flopped and been really at peace with myself and felt grounded. It's my own relationship to the art that has to stay in a place of the spirit, or else I'll get lost quickly.

What do you hope your fans will learn about you after listening to Ben?

There's a common desire to be understood. That is a throughline through the human experience. We want to be seen. The beautiful thing about art is that I have no idea what people's interpretation is going to be—and that’s how it’s supposed to be. I don't want them to feel a certain thing. I want it to be completely open for interpretation and hopefully change. When I go back and hear Aquemini, I hear it differently than I did 20 years ago. It’s a different record. To me, it sounds different. I’ve grown as a person, so I hear bars a different way. It’s not this finite piece of art, it keeps taking on a different life. That’s how I want Ben or any other body of work I put out to be.