It wasn’t long ago that cigarettes were content with just slowly killing the people who smoked them 10 or 20 times a day. More recently, the tobacco industry wants to do away with itself, too. In an act of slow-burning suicide, one of the world’s biggest manufacturers of cigarettes has chosen to quit smoking, stubbing out a multi-billion dollar business on the back of its own hand.

In the summer of 2021, Philip Morris International announced that it intended to “un-smoke the world”, including stopping the sale of Marlboro cigarettes in Britain within a decade. Audaciously, the tobacco giant also proposed the notion of “a world without cigarettes”. It called on the British government to actively ban the sale of its tobacco products, with Philip Morris International CEO Jacek Olczak suggesting that the UK should start treating cigarettes like petrol-powered cars, the sale of which is due to be banned from 2030.

An interesting approach when one considers that, just two years ago, Philip Morris’s Marlboro brand was the world’s most valuable tobacco product. Estimated to be worth $33.6 billion, Marlboro’s value sat alongside brands like Nike and American Express.

And get this: with its marketing muscle now fully behind the IQOS e-cigarette, a device that heats tobacco to deliver nicotine without the smoke and tar that cause diseases, including cancer, Philip Morris planned to reposition itself as... wait for it... a “health and wellness” brand.

At epoch-defining, culturally seismic moments like this, it is, one feels, important to spare a thought for the cruelly victimised community who will be most acutely affected by such a game-changing decision: the supermodels.

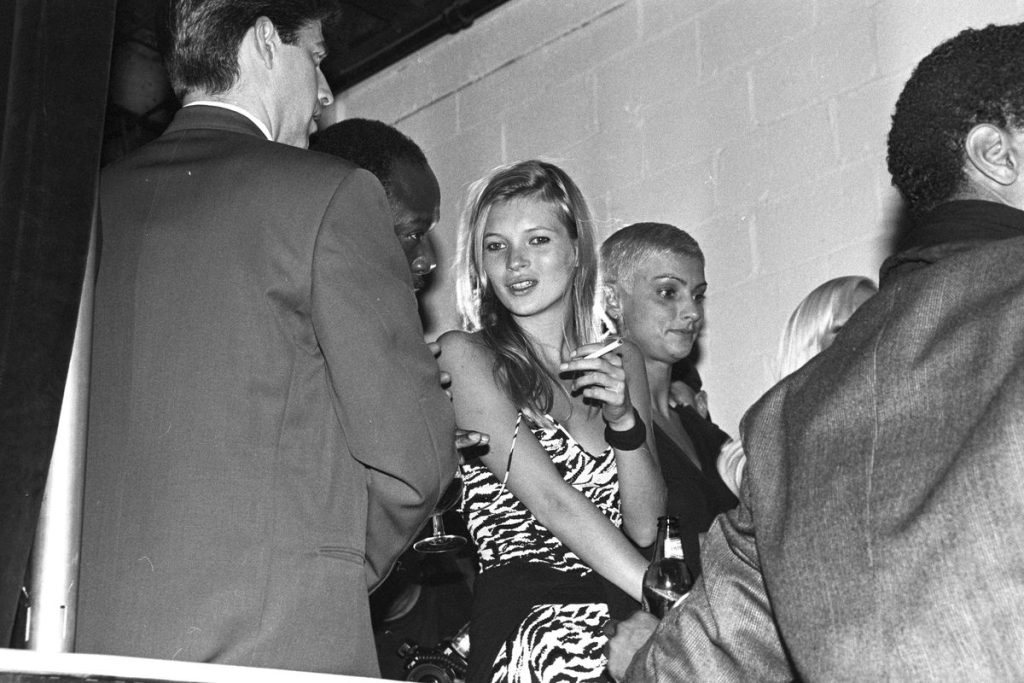

Without Marlboro Golds (the cigarette formerly known as Marlboro Lights and still called that by, well, everyone) what on earth is Kate Moss going to do? What will the fashion industry X-rays in Paris, Milan and London do with their hands and mouths between shows, looks and shots? How will the stylists, photographers, PRs, party organisers and model -agency mavens get through the day without a draw on their cork-tipped cylinders of poisoned pleasure?

Hard to believe, now that smokers have become pariahs and outsiders (quite literally, dar-ling), but throughout the naughty 1990s and beyond, Marlboro Lights were everywhere, as ubiquitous as drop-waist Maharishi combat pants, Nike Air Max and “Wonderwall”. Back in those days, an old party-hard friend of mine would stop at his front door every time he ventured out for an evening — so that’s every single evening for a decade — taking a second to ensure that he had everything he required, in hand or pocket, for the next few hours’ carousing. He called it the “C-check”: cash (for cabs and cocaine), credit cards (for cocktails and champagne) and, most crucially, cigarettes. Marlboro Lights, of course. No other brand was acceptable.

At times it seemed as if the whole of Swinging London was bumming from the same pack

My pal knew, as we all did, that those perfectly formed paper tunnels, packed tight with heady brown leaves, were social mobility sold in crush-proof packs of 20. Mini chimeneas of glowing orange and sweetly intoxicating acridity that flirted and swaggered, even on the lips of dorks and in the hands of wallflowers. Simply everyone who smoked, smoked them.

In 2021, smokers are regarded as bad influencers, but in previous decades they were cover stars, rock stars, Soho blades, record-company tyros, movie directors, Primrose Hill yummy mummies. And, at times, it seemed as if the whole of Swinging London was bumming from the same pack.

Though truly a global product, Marlboro Lights seemed to flaunt a certain London look (the brand was named after a Philip Morris factory on Great Marlborough Street, W1), neatly and expensively and serendipitously positioned as the vogue cigarette long before Vogue cigarettes became a thing. More than just a smoke, they were a pop icon, with their architectural logo, its letters crenelated like the Manhattan skyline, pack graphics designed in geometric, constructivist style by Frank Gianninoto.

Launched in the 1920s, advertising for Marlboro was originally based on the cigarettes’ “lady-like” filter tip (big tough men obviously preferring their smokes full strength and unfiltered). Marlboro’s cork filter had a printed red band around it to hide lipstick stains. “Beauty Tips to Keep the Paper from Your Lips” went the sales blurb.

The Marlboro Lights’ foggy hegemony and swanky social mobility was baffling and frustrating for its rivals, who spent just as much on sponsoring F1 teams as they did but couldn’t quite get in the game. Indeed, so all-asphyxiating was the great American smoke in the Big Smoke during the last millennium that other brands were forced into guerilla marketing tactics in order to stay competitive.

At Oliver Peyton’s wildly fashionable Atlantic Bar and Grill in Piccadilly, cigarette girls would walk the floors brandishing trays of Camel Lights. If they spotted some hipster inhaler — Bono or Helena Christensen — with a pack of Marlboro Lights next to their Cosmopolitan cocktail, a Camel cutie would insert herself and offer a whole pack — gratis — so long as the celebrity smoker stubbed out his or her Marlboro Light and sparked up a Camel instead. It didn’t work. Marlboro Lights carried on being the default-setting smoke for bad-boy actors and 3am-eternal fashion mannequins; girls who lit boys who lit girls who lit boys, as the Blur song goes (nearly).

How much was Philip Morris paying Kate for this incredible PR? Zip. Zero pounds

But it was getting the supermodels on board that was Marlboro’s greatest, accidental coup. All the big girls knew that a pack of Marlboro Lights a day kept the hunger at bay. Especially when paired with copious sea breezes and the company of a lizardly rock star.

And then there was Kate Moss, perhaps the greatest smoker of all time. During the 1990s, Kate was said to be raking in around $10 million a year from contracts with Burberry, Chanel, Calvin Klein and more. But her most loyal and gilded partnership was surely with the Marlboro Lights flip-top pack, which she promoted with reliable and casually professional zeal. Pretty much every night, for around 20 years.

How much was Philip Morris paying Kate for this incredible PR? Zip. Zero pounds. Kate was Marlboro’s coolest and sexiest brand ambassador— and she did it for free. For the love of the warm glow of the yellow flame ignition, the long, noirish drag, the fuggy blast of sweetly noxious, bluey-grey cloud.

And now? Time for Kate — and the rest of us — to prepare for a world without the Marlboro Golds. Either that, or move to the developing world. No plans, so far, to stop selling the cancer sticks there.

Simon Mills is a contributing editor to Esquire. This piece appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Esquire UK.