…I was five, I was the happiest whenever we took a drive—anywhere and no matter how short the distance. You had a pickup truck then, an upgrade from the massive lorry you had to drive for work. It thrilled me to sit at the open back with the wind beating on my face, and reacting to every bump and turn with glee as I treated the experience like a rollercoaster ride.

…We first moved into our first and only home as a family, it was important that you had a whole home theatre system complete with a LaserDisc player and karaoke paraphernalia. We’d spend some nights singing everything from English classics to Malay Pop, with every door and window closed so we wouldn’t disturb our neighbours too much. Little did you know that that would ignite my passion for singing and music in general.

…I was eight, you arrived late to my birthday party at home. You had a bag in your hand, and in it was a set of new clothes. You asked me to change into them for the party. I did, and then realised that you took inspiration from a Cerisi (a now-defunct ’90s kidswear brand) advertisement that was pretty much on every television ad slot. It was funny to me then, and in hindsight, makes me realise that you were still figuring out this whole “being a father” thing because I was your first.

…I was 10, we went for a big family trip to Australia’s Gold Coast. It was our first time travelling outside of Asia, and you opted not to follow a tour group. You’d spend each night figuring out the maps and planning out drive routes so we didn’t waste too much time travelling. This was before GPS became a common everyday tool, and because you hated spending money on maps, you printed out pages and pages of route information for subsequent trips to Australia’s other states. You taught me how to read them so that I could guide you whenever we were on the road.

…I was 11, you had your mother’s side of the family over for dinner at our home. As we started eating, you decided to announce that we were about to add another member to the family. You didn’t realise it then, but he would grow up to be almost a carbon copy of you in ways that baffle me to this day. I didn’t realise that I would eventually appreciate that, especially in the past couple of weeks, because we’re quite different, you and I.

…I realised that our birthdates were the reverse of each other’s, I thought it was pretty cool. I tend to forget a lot of things, but I could never forget your birthday.

…I was 16, my secondary school enrolled the entire graduating cohort in a motivational workshop (that workshop that is familiar to most Singaporeans). It was designed to help us learn nifty studying techniques and spur us to work hard for the upcoming GCE O-Level exams. Part of the workshop included a session where trainers would suddenly guilt-trip us by way of eliciting emotional responses in the hope of triggering a mindset change among us teens. I texted to say an unprompted I love you after that particular session. I don’t think I’ve ever said it to you again.

…I did horribly for my GCE A-Level examinations, you didn’t express disappointment; you sought alternatives. You brought me to a seminar to learn and understand more about studying overseas. “We have money set aside for your education,” you said. You felt assured after the seminar that there was at least hope that I could still be a degree holder, but you also knew that if I were to study overseas, the chances of my coming back would be slim. We ended up not choosing it because I didn’t know what I wanted to do at the time.

…I turned 18, and you paid for me to start taking private driving lessons. The instructor was your friend—one of the many friends you’ve made in your lifetime—and you’d check in with him to ask about my progress. To be honest, it wasn’t difficult at all because I grew up with you driving by my side. You were my first driving instructor, just as you were my first mentor in so many other areas. I learnt just by observing you.

…We asked for forgiveness every Eid since I turned 25; there was a consistent thing that you’d say each year. I want you to be more present and involved; sometimes I feel like I only have one son. It hurts every time I heard it, but it’s a reminder that I needed to hear.

…You were hospitalised for the first time ever; it was just the two of us at the observation ward. We talked about a bunch of random things, including how you were disappointed with the way a marital issue was handled by your side of the family. It was the first time in a long time that we agreed on something.

…You were first diagnosed with cancer, I felt the need to not visibly react to the news. We have a history of not being emotional in this family, and despite me being the most emotional one in every other circle, I couldn’t break down in front of the family. I went to my room, closed the door, and cried. I had just lost a friend to cancer a month before.

…It was just the two of us on our drives to the hospital for therapies and medical appointments, you’d attempt to make small talk about things remotely related to fashion. You’d mention a friend of a friend of a friend’s son who “dresses in expensive things like you” or ask me if Donald Trump’s economic decisions would affect my work. The latter inspired me to write a feature.

…You had to go through a six-hour chemotherapy session—or any length of one for that matter—you’d ask me to head back to the office, assuring me that you’d be fine on your own. I never did because I wanted to be at your beck and call. I felt powerless and useless because there was nothing I could do to help, so the best thing I could think of was to be around as much as possible. It was at those times that I witnessed the physical decline you were going through. For the first time, you could fit into my clothes—you’d wear my T-shirts that were mistakenly placed in your wardrobe.

…You were told the cancer had spread to your bones and other organs, you were crushed. I had never seen you sob uncontrollably until that night.

…You were admitted for two weeks in the hospital, it was the longest time you have ever spent in one. On one evening, I visited you after work. You were already asleep. I sat next to you and watched you stir and sleep for half an hour until visiting hours were over. It felt strange seeing you that way, and at the same time, made me realise how much time had passed.

…You had to get an IV drip set up by the nurse, I had to hold your hand because you kept trying to remove the nasal cannula that was supplying you with oxygen. You were in and out of sleep the entire day, and doctors had been telling us that your condition was abruptly worsening. Your chest suddenly stopped moving. “I think he’s stopped breathing,” I alerted the nurse. He tapped your chest and called out your name. It must have been 15 seconds before your chest moved again. And then it stopped.

…Your body had to be transported from the hospital back home for us to get ready for the funeral rites. I stayed behind to accompany you. It was four in the morning, and I had never experienced the hospital as quiet as it was. I sat silently in the passenger seat as we drove home; your body at the back of the van, and me attempting to process the last few hours.

…You were about to be prayed for before we made our way to the cemetery. I was surprised by the number of people who had turned up on a Thursday morning. My brother, uncles and I were sequestered in a room for an hour to clean and prep your body for the burial, and when we finally came out with you in all white, there were just too many people that we had to move the prayers to the void deck. It was a true testament to your friendly, social nature and how you valued relationships.

…I woke up the next day, it felt surreal. It still does. I spent the next few days nodding obligingly to relatives and your friends, who all seemed to have the same rehearsed line: “It’s now your responsibility to take care of the family.” I hated it. Because I don’t need a roundabout reminder that you’re no longer here.

…I wrote this; it had only been two weeks since you passed. I tried to go about my days as per normal. I tried.

…We talk about you now, we talk about you in the past tense; we refer to you as “late father”. But I choose to believe that while your time being alive has stopped, your time with us has not—like how grieving never truly ends, one just lives with it.

Congress shall make no law respecting freedom of the press... but keep an eye on evil dwarves with lots of money. From The Guardian:

Staffers at the Post have been on edge for weeks about the rumoured cuts, which the publication would not confirm or deny. “It’s an absolute bloodbath,” said one employee, not authorised to speak publicly. During a morning meeting announcing the changes, editor-in-chief Matt Murray told employees that the Post was undergoing a “strategic reset” to better position the publication for the future, according to several employees who were on the call.

The body count is over 300 employees, a third of the Post’s workforce. Its books section is gone. Its international reporting will wither and likely die. And, as a point of personal privilege, the Post’s legendary sports section will evaporate. In my daily sportswriting days, there was no better or more talented crew to hang with at various events. I remember at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, I decided one day to write a column on water polo, of which I knew nothing. About five minutes after I sat down, the late Ken Denlinger of the Post sat down next to me. “So,” he said, “what’s going on in the game?” How in the hell do I know, I answered. “Well,” he said, “you’ve been here longer than me. You’re the veteran.” If there’s anything about those days that I miss, it’s the camaraderie of the press box, and it was always a party when the Post gang was there—Tom Boswell at the baseball games, Mike Wilbon and the late John Feinstein at some basketball arena or another, the great Sally Jenkins anywhere.

Ominously, and vaguely, Murray said that the revamped Post will consist of efforts that “will be focused on covering politics and government, and the paper will also prioritise coverage of nationals news and features topics like science, health, medicine, technology, climate, and business.”

The rub, of course, is that there’s no evidence that current management knows how to do any of this.

It began, of course, when Jeff Bezos took a pot of his Amazon money and bought the Post. (On Wednesday, one of the people laid off was the reporter who covered the Amazon beat.) Bezos brought in as publisher a Brit named Will Lewis. Management tomfoolery, such as when Bezos made an 11th-hour decision to pull an endorsement of Kamala Harris, a blunder that cost the paper an estimated 250,000 digital subscribers, ensued. And, in a tough climate for daily newspapers, that came with a price that was paid on Wednesday. Democracy, the Post says, dies in darkness. Newspapers are murdered in broad daylight.

Originally published on Esquire US

Is it sensible marketing or a happy coincidence that Le Labo released a new floral-forward scent during the month of the Spring Festival? We don't know the goings-on of how the universe (or the promotional machine) operates but, at least we have something to pair with our Chinese New Year outfits.

The Le Labo Classic Collection expands its number by another scent. This time, it is a fragrance that you can't put your finger on. While some notes are instantly classifiable, violet isn't one of them. For VIOLETTE 30, this is a scent that refuses to settle on a single mood, identity, or meaning.

Inspiration is taken from the language of flowers, where violet sits comfortably in multiple states: symbolising innocence and desire, humility and resolve, restraint and passion. Rather than resolve these tensions, VIOLETTE 30 leans into them. White violet is the main ingredient, and it differs from the usual powdery version often used with cosmetics or nostalgia. It opens with verdant green floral notes before unfurling into a calming white tea. Anchoring the composition is cedarwood, a dry warmth, while guaiacwood adds a smoky, resinous depth.

There's an appeal of a scent that is in flux; an insinuation that when a body contains multitudes, that many facets are best embraced rather than distilled; that's one way of looking at VIOLETTE 30. (And perhaps, you've already fit VIOLETTE 30 into a convenient bracket and THAT IS FINE, AS WELL.)

As usual, every bottle is blended fresh and labelled with a personalised message of your choice. Available in 50ml, 100ml, and 500ml formats, you can use the same Le Labo bottle or any kind of container, where VIOLETTE 30 can be refilled into at select labs worldwide at 20 per cent off the retail price.

The VIOLETTE 30 is now available at all Le Labo outlets and online.

A quick glance at Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso Hybris Artistica Calibre 179 brings to mind a few visual images. Rolled sleeves and symmetry. The cat’s whiskers and architecture. The Ritz, theatre and jazz. Now, none of those words you just read has anything to do with the watch we’re discussing at hand—but all of it is tied together by a single common thread: the Art Deco period.

We know this of Jaeger-LeCoultre by now. The brand is class and glamour objectified on the wrist. Its visual language always seems to harken back to a time when rich people appeared to exist perpetually in gilded bars, cocktail glass in hand, brass panels overhead. The Reverso, in particular, was conceived and designed at the height of the Art Deco period in 1931. This aesthetic has since been retained within the brand’s heritage story and retold to the generations that have come after.

With all that being said, is it a stretch to suggest that the Reverso Hybris Artistica Calibre 179 feels like the most Art Deco-looking watch the Maison has released in recent history? Of course, immutable elements of the reverso remain: signature gadroons above and below the dial, and the deeply engraved sunray pattern on the inner carriage. But then there are other elements, like a black lacquer dial that almost mirrors the glossy surface of a Steinway piano. Surrounding the dial is a network of intricate lattice webs that form the decorative plates and bridges. Woven between some 200 depressions within the metal web contains the same lacquer in black and grey that’s been hand-applied to achieve a consistent layer of visual depth—resembling the polished geometrical floor tiles you’d find in a swanky bar.

If you’ve been keeping up with Jaeger-LeCoultre’s endeavours, you might find these elements of craftsmanship familiar—and you’d be right. The watch in question is the second iteration of the Reverso Hybris Artistica Calibre 179, which was first released in 2023. The latest model switches out the previously white gold case in favour of a pink gold one, which we feel really hammers home that Art Deco glitz and glam.

The 1920s and 1930s were a significant time for technological advances. From electrification to radio, telephones to cars, and airplanes to skyscrapers—the period forever changed how people moved through life. The Hybris Artistica Calibre 179 mirrors that zeitgeist of advancement with the fourth evolution of the Maison’s Gyrotourbillon.

Developed specifically with the reverso in mind, an intricate dance of cages and carriages occurs right between the lacework of pink gold and lacquer. The inner tourbillon cage torques against itself, completing a 360-degree rotation once every 16 seconds. Meanwhile, the peripheral carriage that cradles the inner tourbillion cage rotates once per minute, creating a mesmerising movement that churns and dislocates in tandem, ironing out any gravitational errors while enhancing timekeeping precision.

By employing a ring of ball bearings instead of a conventional bridge, the Gyrotourbillon is given the illusion of levitation between the front and back dials. This not only lifts the gyrotourbillon to live up to its “flying” moniker but also affirms Jaeger-LeCoultre’s grasp of blending the science and art of horology. After all, over 180 skills between watchmakers and artisans were brought together under the Jaeger-LeCoultre roof to bring this watch into fruition.

We get front row seats to proof of this sentiment when we slide-and-swivel the case around, revealing the intricate symphony of gears, balance wheels, and balance springs that bring this watch—that’s limited to just ten pieces worldwide—to life. Users will be able to adjust the 24-hour indicator on the skeletonised reverse dial to the time of a different zone.

The Reverso Hybris Artistica Calibre 179 has a power reserve of 40 hours and runs slightly larger in dimensions when you compare it to their usual offerings. At 51.2 x 31 mm, it’s to be expected. Come on, we’re dealing with grand complications here!

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso Hybris Artistica Calibre 179 is limited to just 10 pieces worldwide

The first day of school is always daunting. Plenty of unfamiliar faces, a sprawling campus and a schedule to follow. It’s also exciting. The promise of a new experience. The fostering of meaningful relationships. And much to learn. Welcome to the academy, freshie.

The entrance spares no expense. Two colossal iron Phu Quoc Ridgeback dogs symmetrically flank the entry, resting atop the emblazoned gold letters in varsity font: BIENVENUE À TOUS UNIVERSITÉ LEMARCK. Spot a miniature version of the pair along the road in; one amongst the pattern of visual palindromes of animal statues guarding the domain. A giant trophy takes center in a courtyard pond, and the gaze soon follows the college memorabilia adorning the halls.

You are forgiven for believing that the hotel now occupies a former French-colonial boarding school that was abandoned in the 1940s. The embellishments carry such a level of detail—black and white cohort photos, team jerseys of rival institutions, distinguished portraits—that the legacy is almost palpable. The fictional university derives its name from a real-life French naturalist, grounding the storylines behind what is otherwise a highly imaginative concept for a Marriott, or any hotel for that matter.

Those familiar with Bill Bensley’s work would recognise his whimsical touch. Fueled by the desire to push the envelope, Bensley reframed a conventional beach resort to echo the best season of most of our lives: college years. Staff attire resembles faculty uniforms, fashioning them as fellow students rather than teachers. The guest information pamphlet is embodied in a student handbook. Blocks are assigned as departments spanning Ornithology, Ichytyologie, and a slew of other -ologies you’ve never heard of.

Every aspect is so committed to the bit that it’s no longer a bit. Find fun facts according to their respective departments in each lift (did you know the number one killer creature by total death count is the mosquito?). Even the running track features an unmissable Home Vs Away scoreboard. Architecture is distinctly Indochine, but the vibrant paint job viscerally evokes a theme park town. The immaculate upkeep of the grounds, however, does not give away its age.

Like the eclectic mix of written and painted murals (including one quote of Walt Disney himself) dotting the estate, the fitness center is just as extra. Apart from modern machinery, it is spruced with elements of a vintage gymnasium. It’s one of several instagrammable corners that the resort map marks out for your consideration.

The three pools are sensibly free from the kitsch, but their wave-inspired shower areas are a nice touch. All fringing the welcoming views of Khem beach, which can vastly change its hues depending on the weather. It’s no wonder that guests opt for the classic water activities provided spanning paddle boarding, surfing and kayaking.

Three days’ worth of breakfasts was not enough to try everything that was in Tempus Fugit’s incredibly diverse spread. Encompassing the greatest variety of cuisines, the all-day dining still manages to switch up the choices daily. Pho-losophy, its hearty menu that celebrates Vietnam’s famed dish, earns a shoutout for a fantastic rendition incorporating truffle. Savour afternoon tea fresh from French & Co, dine at Red Rum’s ocean-front seating, and continue the revelry at The Department of Chemistry (the bar, of course).

Do save a night for Pink Pearl, arguably the grandest display of the hotel’s mythical narrative. An ode to a second wife that never actually existed, the restaurant has its menu crafted by Chef Olivier Elzer. The 27 Michelin stars to his name and work with industry greats Pierre Gagnaire and Joel Robuchon expresses in a truly stellar French-Mediterranean course. A personal favourite is a brandy “blancmange” of blue lobster tinged with tandoori sauce, bedded under Osciètre and presented in a caviar tin with a pearl shell spoon.

The range of activities at your disposal are cleverly arranged like a timetable. Lantern Room hosts most of them, not limited to, well, lantern-making. If candle creation and other handiworkings are not your thing, there are plenty of outdoor options from cycling to diving. Chanterelle-Spa is a lovely spot to unwind after all that productivity.

Even without indulging in the treatments, the spaces accompanying the steam and sauna rooms are composed with visible care. The peripheral mini shopping street and theatre means you practically don’t have to step out of the resort at all.

But this visa-free, direct-flight island beckons. The shuttle bus conveniently situated outside the main gate takes you to the heart of Phu Quoc’s tourism—Sunset Town. Across the Positano replica is the best panorama of the setting sun framed by a flood of fellow foreigners. Before catching the excessively extravagant evening firework and acrobatic water show, a scenic ride to Sun World Hon Thom on the world’s longest archipelago-crossing cable car is highly recommended.

Book you stay at Marriott.com

Filmhouse, the new indie cinema replacing The Projector at Golden Mile Tower has finally opened its doors. Led by much of the former The Projector team, its theatres feature three screens, upgraded 4K projection, improved sound, and a refreshed interior.

You can expect festival favourites, classics, local titles and tightly curated arthouse films. This weekend’s lineup includes highlights like Hamnet and Sentimental Value, alongside classics like Yi Yi and Little Miss Sunshine.

When: Daily

Where: Filmhouse, 05-00 Golden Mile Tower, 6001 Beach Road, Singapore 199589

Get your tickets here

If you’re reading this, you’re probably one of the rare few who still find pleasure in reading books. If so, listen up! Sing Lit Station has decluttered its office after a decade, and they’ve uncovered a ton of rare and unloved literary gems. For a donation fee of SGD25, you’ll be able to snag as many books as you can fit into a single bag. This includes books, games, comics, and other trinkets and knacks.

When: 7 to 8 February, from 10am to 6pm

Where: Sing Lit Station, 22 Dickson Rd, Singapore 209506

JR East (yes, that JR railway company) is organising a free fair this weekend that showcases Japanese cuisine through the romance of railway travel. Featuring 20 vendors across food, tourism and alcohol, including Nissin Foods, Kiyoken and Matcha An.

Highlights range from JAL’s new farm-to-table subscription service (JAL de Hako-byun Shinkansen Delivery) to izakaya-style pairings—Hokkaido fried chicken skewers with draft KIRIN. There’s also regional delicacies, travel deals, and sake tastings to be had.

When: 6 to 8 February 2026, from 11am to 8pm

Where: Guoco Tower Urban park, 5 Wallich St, Singapore 078881

The National Stadium Experience is back for nearly all of February, turning Singapore’s iconic track and pitch into a playground for everyone. Grab a mate, or a kid (that’s yours), and a jog on the historic track, a kickabout on the field, or try your hand at sports workshops ranging from rugby and Tchoukball to cycling.

The weekends come with bouncy castles (socks required), back-of-house tours, arts and crafts, and even a lion dance to ring in the Lunar New Year. Spots fill up fast, so register early. Entry to the stadium is free via Gate 3.

When: 6 and 8 to 22 February

Where: National Stadium, 1 Stadium Dr, Singapore 397629

Register here

The Singapore Youth Film Festival is happening over the next couple of weeks, where 43 shortlisted films will be on full showcase. Only in its second edition, there won’t be glamour red carpets or celebrity appearances, but you probably already knew that. Instead, there’ll be live action, documentary, and animation genres exploring truths of identity, grief, relationships and the works.

Where: Oldham Theatre, 1 Canning Rise, and SOTA Studio Theatre, 1 Zubir Said Drive

When: From January 29 to February 13 2026, across various screening times

Get your tickets here

Based on The Book of Red Shadows by Singaporean sci-fi writer Victor Fernando R. Ocampo, this immersive experience drops you into the sleep lab as an undercover participant. Part interactive theatre, part escape room, the story unfolds as a choose-your-own-adventure experience.

Here’s the story: SomniTech promises sleep that’s optimised, guided, but quietly monetised using dream-tracking technology. Things get murky when some trial participants are stuck in the programme, and its brilliant, controversial founder Dr Adrian Tan vanishes soon after. It's up to you and your buddies to uncover the secrets of the company and break out of the programme.

Where: The Arts House, 1 Old Parliament Ln, Singapore 179429

When: 9 January to 7 February

Get your tickets here (SG Culture Pass eligible)

Elephant Grounds, a prominent figure in shaping Hong Kong’s café scene for the past decade is landing in Singapore this Saturday. For the uninitiated, the café is known less for theatrics than for doing the fundamentals well: considered coffee, from-scratch baking, and interiors designed to be a third space. Look out for their Earl Grey Doughnut, Banoffee (banana + toffee croissant), Chocolate Cookie, Fish Fillet Sando, and Wildberry Pancake Stack.

When: Daily, from 8am to 8pm

Where: 124 Beach Rd, #01-04 Guoco Midtown, Singapore 189771

PREVIOUSLY

If the intersection between running and meeting new people intrigues you, here’s an event worth lacing up for. Going down every Saturday at the Botanic Gardens, you’ll be able to mingle with like-minded single people as you compare running shoes while the sun sets in the background. Admission is free, and the run is unhosted, which means everything unfolds as naturally as these things ever do.

When: Every Saturday at 7pm

Where: Chopin Overlooking the Symphony Stage, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569

Save a spot here

If you’re feeling adventurous, head down to Dopamine Land for a quick hit of multisensory euphoria. Having toured cities from London to Madrid, the Singapore edition will feature nine interactive spaces. You can wage pillow fights at The Cushion Clash or get jiggy with it on the Chromadance floor. But there are also more calming spaces in case things get too overstimulating. Euphoria Grove puts you in a bean-bag filled sanctuary with lighting that changes according to the four seasons, while the Cave of Tactility cocoons you in a room with soft, colourful textural walls.

When: Daily (except Thursdays), from 11am to 9pm

Where: Dopamine Land Singapore, #02-204/205, Weave, Resorts World Sentosa, 26 Sentosa Gateway, Singapore 098269

Get your tickets here

Back in the day, the games our ancestors played were never just games. They doubled as barometers of culture, power, and community, and the Asian Civilisation Museum seeks to trace and highlight that lineage. From mahjong and congkak to the slow, deliberate logic of go and chess, “Let’s Play” is an exhibition that will feature interactive stations, outdoor installations, school collaborations, and a steady run of talks. Of course, you’ll also get to try your hand at classic and contemporary board games, as well as locally designed ones to flaunt your mental prowess, just like your ancestors (probably) used to.

When: 5 September 2025 to 7 June 2026

Where: Asian Civilisations Museum, 1 Empress Pl, Singapore 179555

Get your tickets here

National Gallery Singapore is presenting Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a substantial look at one of the largest impressionist collections outside France. Look for works by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, and other key figures who will anchor the exhibition.

Spread across three galleries and seven thematic sections, the show brings together more than 100 pieces, a scale rarely seen in Singapore. The installations will also trace how Impressionism shaped artistic developments in Southeast Asia.

Also, it's worth noting that tickets booked before 30 November 2025 come with a 30% discount—so you'll want to move quick if you’re planning a quiet afternoon at the gallery.

Where: National Gallery Singapore, Singapore 178957

When: 14 November 2025 to 1 March 2026

Get your tickets here

Science Centre Singapore and the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum join forces to host Dinosaurs | Extinctions | Us, an exhibition that transports you to the prehistoric world of Patagonia. At the centre of it is a 40-metre cast of Patagotitan mayorum—one of the largest creatures ever to walk the planet. Alongside it are 33 rare fossils and 60 full-scale models tracing 400 million years of evolution and extinction.

The showcase also turns its gaze to the five mass extinctions that have shaped Earth’s history, and a sixth one that’s currently unfolding before our eyes—including a look at species once native to Singapore. Tickets start at $25.90 and include a complimentary plushie.

When: Tuesday to Sunday, from 10am to 5pm

Where: Science Centre Singapore, 15 Science Centre Rd, Singapore 609081

Get your tickets here

Japanese whisky house Nikka Whisky is joining hands with Singapore’s homegrown perfumery Oo La Lab to create a limited olfactory workshop guided by the experts at Oo La Lab. Guests are invited to alchemise their own perfume, drop by drop, based on their interpretation of the Nikka From The Barrel whisky. However, the lab won’t limit you; you’re free to tweak and adjust your scent to your liking, based on over 20 different scents (I think, if my memory serves me right).

Each session not only begins with a welcome cocktail crafted with Nikka From The Barrel, but continues with tastings of Nikka From The Barrel served neat and diluted so guests can explore its base note in detail. But here’s the best part: tickets are priced at SGD98, but everyone gets to bring home a full-sized bottle of Nikka From The Barrel worth SGD85 on top of their personalised perfume. So you’re essentially paying SGD13 for a perfume workshop, which is a BARGAIN. The experience is limited to just 8 sessions for up to 25 participants, so you’ll want to move quick.

When: Thursdays at 6pm, and Saturdays at 2pm

Where: Oo La Lab, 2 Alexandra Rd, #02-04 Delta House, Singapore 159919

Get your tickets here

Sir Ben Kingsley is one of the most acclaimed and prolific stage, film, and television actors of his generation, with a career spanning more than five decades. He won an Oscar for Best Actor for his role in Gandhi (1982). Kingsley appears in the comedy The Thursday Murder Club, out now on Netflix.

I FIND IT EASY TO RELAX. I think confidence has an awful lot to do with it, and a certain degree of accomplishment. I don’t mean that in a pompous sense. If I were struggling as a craftsman, I would tend to walk around with the tools of the trade in my hand. Now that I feel more wedded to my craft, I can put my tools down.

I TRY NOT TO use the word love lazily.

HUMANS ARE, BY NATURE, expressive. I didn’t say I wanted to be an actor until I was 18, but when I was a child, I saw a film called Never Take No for an Answer. It starred an Italian orphan who looked like me. Or, to put it more modestly, I looked like him. When we left the cinema, the theatre manager lifted me above the crowd, saying, “It’s little Peppino.” I felt quite exhilarated being held, because I really believed I was that little boy on the screen, and I wanted to tell his story. It moved me to tears—it still does.

MY DAD WAS VERY PRAGMATIC and said, “Change your name.” [Kingsley was born Krishna Pandit Bhanji.] If it comes from a parent, it has weight, so I did. It’s as though I’m a painter and I sign my canvases Ben Kingsley, because that’s what they are.

I DON'T THINK it would have been remotely possible for me to enjoy the company of Richard Attenborough on that extraordinary journey of Gandhi had I not had 12 years with the Royal Shakespeare Company. If history had not created Gandhiji, either Shakespeare, Tolstoy, or Dostoyevsky would have. It’s just destiny. A silhouette of monumental qualities, of repercussions, echoes, significance.

TO BE ABLE TO LOOK AT MY OSCAR in the corner of this lovely room at home in Oxfordshire is absolutely astonishing. My fellow nominees were Peter O’Toole, Jack Lemmon, Dustin Hoffman, and Paul Newman. It was my first real experience of cinema and, knowing the business as much as I do now, the award gets mentally polished every year.

I DO NOT THINK STRATEGICALLY. Everything is a delight. Everything is an extraordinary surprise.

I’VE HEARD THIS PHRASE, where you “win the scene.” It was actually said in front of me on set quite recently, to my fellow actor. It was as if the director had no concept of the fact that it was a duet and one must not encourage one singer to sing louder than the other, because it’ll go off-key.

ON THE SET OF The Thursday Murder Club, thanks to the extraordinary qualities of Christopher Columbus, everyone was Spencer Tracy. Now there’s an actor who was riveting. One of his sayings was: “Make the other guy look good.” Isn’t that beautiful?

“DON'T PROJECT ONTO THE OTHER” is, I think, a good lesson for life. I would not say it’s exclusively reserved for marriage. Listen and admire and cherish the other’s separateness.

I TEND TO be a hermit on a film set. I say that quite respectfully to my colleagues at the beginning of a shoot. I love to disengage from a scene and let my elastic snap back to its original shape, and then stretch my elastic between action and cut. If elastic matter is stretched beyond its point of elasticity, it can no longer shrink back to its original self. Now apply that to acting: It can be very dangerous.

I KNOW THAT SOME of the most sublime moments in my life are between action and cut. They defy chronology.

THE CAMERA LOVES DISCOVERY. Where being rather reclusive pays off is when I get onstage. Let’s say I’m with Pierce Brosnan: We both tend to be rather private. We are then discovering each other on camera. It is gold. You can’t manufacture that body language of curiosity, the inflexions in the voice. It is totally natural and organic.

I STILL GET HORRIBLY NERVOUS on film sets. I still am terrified of letting everybody down.

I FIRST SAW MY CHILDREN act when they joined a marvellous outfit in Warwickshire. Edmund was playing Prince Hal, and Ferdy was playing Falstaff’s page. [Kingsley’s other two children are Jasmin and Thomas.] Something in me deeply relaxed when I watched them and said to myself: Oh yes, they can do it. When my boys came out, I think I dislocated three of their ribs.

I HAVEN'T PLAYED Lear, and I have no wish to. I’m exploring him prismatically through other roles. Gandhi was Hamlet and Lear together. I did a film last year called Jules, and I said to the director: “This is one of my Lears.” I have occasion to go through Lear’s dilemma and journey, and even wildness, through other means.

WHAT SURPRISES ME about ageing, because I’m blessed with great fitness and very good health, is the beginning of wisdom. It’s this small fake tap on my door, saying: “Wisdom here.” I might be getting a little bit wiser. Who knows? We will have to wait and see.

Originally published on Esquire US

They say, "don't judge a book by its cover". To which, we reply, "Who are 'they' and why are you not letting us live our lives?" The same goes for the film/TV/video game industry, where marketing drones and world-weary editors team up to deliver a tasty trailer of what to expect in the final product.

Is it unfair that we are hanging all our expectations on snippets of the main course? Maybe. But is it fun to speculate wildly about what we are about to experience? Yes. Let's get to the last trailers that dropped.

It's the sequel that is heavily prayed for, especially when you work in the magazine industry. You get all the familiar call-backs and cattiness from the last movie. Now you have Anne Hathaway's character, who is more confident and Stanley Tucci still summoning that droll Tim Gunn spirit in his bon mots.

However, the biggest surprise is Meryl Streep, who still remains as stoic, commanding and... ageless, ever since the first instalment came out in 2006. That is indeed evidence of some infernal dealmaking, if we ever seen one.

The last time I watched a movie called Michael, it starred John Travolta as an archangel sent to do menial tasks on earth. This year, we'll get another film of the same name, this time starring Jaafar Jackson, who is stepping into some pretty big penny loafers to portray his uncle, Michael Jackson. Other than the weird prosthetic, Jaafar nails the dancing and the voice but what really clinched it for us is Colman Domingo as the domineering patriarch of the Jackson family.

Thanks to shrewd marketing, our interests were piqued. And this trailer managed to raise our anticipation when Zendaya and Robert Pattinson and friends decided to play a harmless game of confession—"What's the worst thing you've ever done?" Everybody gives some mid reply but when Zendaya answers (we don't hear it), the whole room just stares at her before Alana Haim's character goes, "what the fuck?" and we cut to the rest of the trailer.

What did Zendaya's character say that is seemingly the inciting incident for how the movie unfolds? You bet your bottom dollar that we will be tuning to find out and then see if it's worth it to watch how it all plays out.

We haven't read the book that it's based on but is the trailer enough for us to start watching the series on 15 July? It has a strong lead in Anna Taylor-Joy, who looks like a woman on a run and is also looking to get even—we love a revenge-led underdog. There's also Annette Bening and Timothy Olyphant (the latter, we would watch anything he's in). Oh, and there's a scene of Taylor-Joy walking calmly away from an explosion. That money shot has us convinced.

The thing about a destiny is that it presumes you have no choice. Somewhere along the romantic mythology we’ve constructed around February—Valentine’s Day bleeding into Lunar New Year, the entire month basically asking you to surrender to destiny—we’ve forgotten that the horse was never yours to begin with.

I’m being asked this month to explore what it means to “bet” on something you didn’t choose. Let me start with a confession: I spent years believing choice and fate were opponents. One was supposedly the domain of the empowered, the other the refuge of the passive. What a clean, useless distinction that proved to be.

Consider the etymology of “bet.” It emerges from the old phrase “to set,” with roots in wagers and risk. To bet is to stake something—your money, your pride, your time—on an outcome you cannot control. And here’s where the paradox of the human animal reveals itself: we are constantly making bets on precisely the things we didn’t choose. Our families. Our bodies. The city we were born in. The year we turned 18 and thought we’d begun making independent decisions.

The horse, in any good metaphor, represents the thing that carries you forward despite your intentions. You board it believing you’re the rider. Turns out, you’re mostly a passenger, holding the reins of something with its own momentum, its own will to move in specific directions, whether you’ve approved the itinerary or not. And February—this collision of romantic obligation and cultural fortune-telling—is precisely when we’re supposed to reconcile ourselves to this.

I know a woman who spent three years resisting a relationship she’d accidentally fallen into. Met the person at a work function, texted to decline a second meeting, somehow ended up at coffee anyway, then dinner, then the whole ungraceful accumulation of shared space that masquerades as love. She kept waiting for the moment when it would feel chosen. It never did. What it felt like instead was momentum—the horse moving forward, and her discovering, mid-ride, that she’d somehow become invested in where it was going.

This troubles our narrative. We want romance to be an active declaration: I choose you. But actual human connection mostly comes as an accident; you gradually decide to stop resisting. It’s less “I will ride this horse” and more “I’m already on the horse, now what?”

The cruelty of February is that it demands this reconciliation happen precisely when the entire culture is screaming about intention and destiny. Valentine’s Day insists that your love is a choice you make deliberately, a gift you wrap and present. Lunar New Year whispers that fate has already decided your fortune, that you’re simply finding out what was written. And you’re supposed to feel both things simultaneously—entirely free and entirely bound, author of your love story and character in someone else’s narrative.

What’s fascinating is how often the people who seem most certain about their choices are actually the ones most in denial about the horse. The entrepreneur who believes she self-made her way to success (luck, timing, being born into resources, having a mentor appear at precisely the right moment). The person in the relationship who insists he made a deliberate decision to marry her (after the accidental meeting, the unplanned pregnancy, the series of practical compromises that calcified into commitment).

The real bet isn’t whether you’ll choose the horse. You won’t. The real bet is whether you’ll bet on it anyway—whether you’ll accept that you did not design some of the most important trajectories of your life, but only inhabited by you, ridden by you, eventually loved by you.

There’s a Japanese concept, meiji, that translates roughly as “the will of heaven.” It’s not fatalism exactly—it’s more sophisticated than that. It’s the recognition that some things arrive unbidden, and the measure of a person isn’t whether they managed to arrange their own destiny (spoiler: nobody does), but whether they could recognise a gift when it landed on them, even if it wasn’t wrapped the way they’d imagined.

Consider the etymology of “bet.” It emerges from the old phrase “to set,” with roots in wagers and risk. To bet is to stake something—your money, your pride, your time—on an outcome you cannot control. And here’s where the paradox of the human animal reveals itself: we are constantly making bets on precisely the things we didn’t choose.

I think of this when I observe people in February. The ones anxiously assessing whether their relationship is “right,” as if rightness were something you could verify beforehand. The ones making resolutions about fate, as if they could negotiate with the cosmic machinery. The ones insisting they’re in control, when what they’re actually doing is deciding which unbidden trajectory they’ll commit to.

Here’s what I’ve noticed: the people who seem most at peace aren’t the ones who orchestrated their lives perfectly. They’re the ones who got on the horse they didn’t choose and decided to become excellent riders anyway. Who looked back at the accident of their education, their love, their circumstance, and said: Ok, I bet on this. Not “I chose this,” but “I choose to ride it well.”

The horse metaphor has another edge, though. Sometimes the horse is running toward a cliff. Sometimes it’s pulling you in a clearly destructive direction. The wisdom of being unbowed—of remaining standing when everything suggests you should break—includes this: you can get off. You can choose to fall, to leave, or to walk in the opposite direction. That’s also a bet, and often it’s the more courageous one.

But most of us aren’t on runaway horses. We’re on horses that are going broadly in a defensible direction, and we’re still waiting to feel like we chose to get on. We’re still waiting for the moment when it will feel intentional instead of accidental, decided instead of drifting into.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth February is asking us to sit with: that moment might never come. What comes instead is the slow realisation that the trajectory you didn’t choose has become the life you’re actually living. That the person you fell in love with has become essential. That the bet you never consciously made has become the only bet that matters.

The romance industry wants to sell you the fantasy of the deliberate choice. But the more honest story—the one February is actually whispering beneath the music and the algorithms—is that most of us are riding horses that found us. The question isn’t how to regain control. The question is whether we can become the kind of person who bets on the unbidden, who says yes to the accident, who finds dignity and even joy in discovering that the path was never ours to choose but only ours to walk.

So here’s to the horses we didn’t pick. To the relationships that arrived as accidents and became as essential as breath. To the understanding that some of our best bets are the ones we never consciously made.

Fate and fortune are real, it turns out. Not because the universe is written. But because we’re willing to read what’s already in motion and say: yes, I’ll ride this.

On 27 January 2026, the hands of the Doomsday Clock—repositioned each year by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to reflect existential threats facing mankind and our planet—were set to 85 seconds to midnight, the closest the clock has ever come to forewarning armageddon.

In the 2021 issue of Esquire's Big Watch Book, we spoke to Rachel Bronson, who oversees the Doomsday Clock in her role as President and CEO of Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. You can read our (in retrospect slightly too hopeful) Q&A below.

What is the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists?

The Bulletin is a 75-year-old organisation that covers man-made threats to humanity. When we started, we covered nuclear issues, now we also cover climate and disruptive technology. We publish every day on these subjects. You may have heard of the Doomsday Clock, that represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe.

Why has the Clock captured our imagination?

Because it’s simple. Because it’s blunt. Big existential issues can be daunting and overwhelming; science can be intimidating and off-putting. So the Clock does what scientists are unable to do and connects with the audience, to really give them something to talk about. In the setting of the Clock we ask the experts to do something very, very uncomfortable. We ask them to set aside all nuance and say: are things getting better or worse? Or are they staying the same?

What do you mean by “nuance”?

How do you compare nuclear risk, climate change, advancements in artificial intelligence, advancements in bioengineering, lab security? Say you’re a really advanced climate scientist, how much do you know about neurology? Probably very little. The Doomsday Clock rolls up all these issues, and what we need to do is have all the experts available to debate them. It’s a judgment by experts who work on this, day-in day-out.

In January 2021, you moved the Clock to 100 seconds to midnight—the closest it’s been to Doomsday since it started in 1947.

Well, the hope is always that we move it backwards. It was a very big deal to go to two minutes to midnight [in 2018], the closest it had been since the 1950s. In 2018 we thought things were as dangerous as they were in 1953. In the 1950s we were building the technologies, and then in the 1960s and 1970s we were building an architecture to keep the technologies at bay. And there was some sense of international cooperation that together we could figure this out. It was always hard-fought and hard-won but there was commitment. The pandemic was an opportunity, a global crisis where we could have come together. And we ended up with finger-pointing and organisations walking away from the World Health Organisation.

On the upside, you’ve got to think 2021’s been a bit better! You announce the Clock position each January. What will it be next?

I think there’s been real reasons for optimism. And what science can bring us, in terms of how unbelievably quickly we can get to a vaccine and then to distribution. The Biden administration, with the Russians, have had a new start. In terms of climate and the annual UN conference, the fact that it didn’t fall apart when the United States walked away is a huge sign of success. In history we—as in we, the people—have moved the Clock away from midnight [since 1947, the Clock has been moved backwards eight times and forwards 16 times]. And we can do it again.

The kids will save us!

Right? The older generation are looking at the younger kids, like, “We’re so sorry. Your generation will work out how to fix it.” They get it. They just don’t know what to do about it. Fifty per cent of our audience is under 35 and 50 per cent is outside the United States. They’re more engaged than we were. They’re surrounded by so much existential threat, by politicians who seem to have no barriers for what kind of misinformation they’ll put out. People more than ever have a sense that things aren’t going in the right direction. We don’t seem like these crazy experts who are, like, “the sky is falling in!”

That’s an interesting way of looking at it

We get e-mail and social media, as you’d imagine, on both sides. Sometimes someone starts, like, “You’re scaring my kids!” At the same time, I’ll get an e-mail from someone: “Thank you for acknowledging it. Because it didn’t feel like it’s going well.” Our motivation is to get people involved. And that’s what’s going to turn back the Clock.

What about Watchmen? Pretty good, right?

Anytime the Doomsday Clock appears in popular culture it’s useful to advance discussion. We appreciate it. Not everyone is going to want to learn more after getting into the comics or watching the TV show. But our hope is that some people will and they’ll be able to find us. Or we’ll be able to find them.

Iron Maiden, Midnight Oil and Sting have all written songs about the Doomsday Clock. As if it wasn’t depressing enough.

We have a Doomsday Clock Playlist on our site! It’s back to your first question: the Doomsday Clock is accessible. It’s used at the highest levels of politics, used in classrooms, in grassroots conversations.

Sting, though.

I actually didn’t know about Sting.

This is quite shallow, but your job title is cool.

It’s probably more often viewed as not cool than cool, but I love it. The cool part is more and more people are seeking us out and sometimes in this world, where there’s so little you feel like you can do, that’s gratifying.

Well, thank you for speaking to us.

Thank you for covering us. I don’t know if you want me to say anything about watches?

Go on then. What watch do you wear?

I recently purchased a Movado. I’m trying to think about what else I have…

Does it keep good time?

I’m very happy with it.

Originally published on Esquire UK

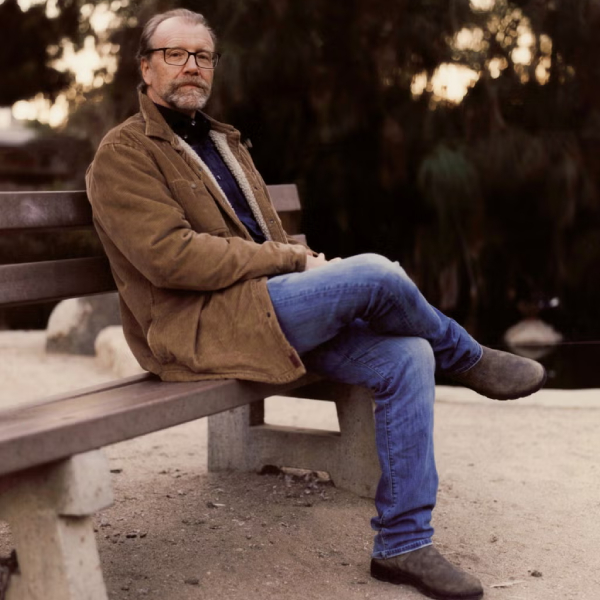

George Saunders insists, despite appearances to the contrary, that he’s not obsessed with death. “I’m not walking around in my preordered shroud or anything,” he tells me over Zoom. But thinking about the dead and dying does put a spring in his step.

“When I get up from writing about it, I feel good,” he continues. “I’m not in bed. I’m not unconscious. It would be amazing if there was a drug that made you feel like total shit for two minutes a day called Here’s What You’re Going to Feel Like on Your Deathbed.”

After writing blisteringly funny short stories for decades, Saunders is perhaps best known for Lincoln in the Bardo, his 2017 Booker Prize–winning novel set during and after the death of Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son. Now 67 years old, Saunders is back with another heartrending novel—Vigil, about the last night of an oil company CEO’s life—which was at least partially inspired by Saunders’s own fascination with mortality.

“I think it’s kind of beautiful that there’s a finite nature to all of this,” Saunders says, gesturing to the world around him. “It’s like you check into a beautiful hotel and there’s a checkout time, but they don’t tell you when it is.”

He does worry about death sometimes—not about what happens after, as he imagined in Lincoln in the Bardo, but about the process of dying, which is at the centre of Vigil. “At my age, people you knew in their prime start going over the cliff, and you’re like, ‘Wait a minute... me, as well?” he says.

“If you go into that final illness without doing any prep, it’s going to be harder, I think. But one thing I’ve observed is, the people I know who’ve gotten that final diagnosis? They don’t panic. They have moments of panic, but in some way I think we’re prepared for it evolutionarily.”

The original idea for Vigil hit Saunders back in the spring of 2023, when a category 5 cyclone killed more than 400 people in the Bay of Bengal and floods disrupted food supply chains around the world. Saunders was watching the devastation unfold on the news when he had an idea.

“I thought about the generation of climate-change deniers in the late ’90s and the early 2000s,” he says—the fossil-fuel lobbyists, think-tank “sceptics,” and dismissive politicians like James Inhofe, who called human-caused global warming “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people” on the Senate floor in 2003.

Saunders wondered how those deniers would feel now, decades later, near the end of their lives, when climate-change-driven catastrophes were constantly in the news. “What does that do to a person as they look back at their alleged accomplishments?” he asked himself. “Does it land at all? Do their mental constructs allow them to keep doing what they were doing, or does the reality break through?”

Armed with those questions, Saunders spent ten to 12 hours per day in the writing shed across the driveway from his house in Corralitos, a small town in the forested hills near Santa Cruz, California, hashing out the first draft of what would become Vigil.

Originally, it was formatted similarly to Lincoln in the Bardo, with “two speakers and a dead guy.” But after throwing those pages out, Saunders adopted a single narrator: Jill Blaine, a young Indiana newlywed who died in 1976 under surprising circumstances I won’t spoil.

Since her own death, Jill Blaine has shepherded 343 people through the last hours of their lives as some kind of nondenominational angel-ghost (my term, not Saunders’s). Her mission? “To comfort whomever I could, in whatever way I might.” Blaine’s supernatural powers provide Saunders with plenty of fodder for his trademark humour.

“I sank through the foundation into the underlying soil,” Blaine says as she passes through solid matter like Casper, “past a rotted wood beam from an ancient barn, half a wagon wheel, a cluster of three cow skulls, and a writhing closet-sized mass of living worms, which, as I passed, came alive with awareness of my presence.”

She also allows Saunders to do some fascinating things with voice, perspective, and character, as Blaine can instantaneously mind-meld with living people (and other ghosts) by simply “whisking” into their “orb of thoughts.” As a result, Vigil is a promiscuous stream-of-consciousness novel that constantly jumps from one stream to another.

As an angel-ghost, Jill Blaine is (mostly) free from the memories and neuroses that defined her as a living person, and she adopts an unconditional sense of compassion for all human beings—even the malicious one responsible for her death. “Who could you have been but exactly who you are?” she says to a dying man. “Did you, in the womb, construct yourself?”

Blaine’s ability to flit from one person’s mind to the next (as writers do) has helped her see human beings as “inevitable occurrences” whose choices in life are “severely delimited” by the “mind, body, and disposition” thrust upon us at birth, through no fault of our own.

“I’ve been having that thought since I was a little kid in grade school,” Saunders says. “I loved getting praised, but when I would do well and somebody else would do bad, a little voice was like, ‘Did you, in the womb, designate yourself a future kiss-up to the nuns?’ ”

In the opening pages of Vigil, which is chapter-less and slim at less than 200 pages, Blaine’s 344th charge, an 84-year-old named KJ Boone on his deathbed with terminal cancer, presents a unique challenge. She wants to comfort him, but he refuses to acknowledge the widespread suffering he contributed to as the CEO of an oil company, where he pioneered climate-change-denial propaganda.

“Boone and his real-life counterparts absolutely committed a huge offence against civilisation—and they did it, apparently, somewhat knowingly,” Saunders says. “By introducing that rhetoric into the world, they gave future generations of deniers, including this current crop, a language that’s very useful.”

After graduating from the Colorado School of Mines in 1981 with a degree in geophysical engineering, Saunders worked in the oil industry himself for a few years, first as an exploration-crew member in the jungles of Sumatra and later as an engineer and technical writer for a firm in Rochester, New York.

“I didn’t think I could do a politician or a PR hack,” Saunders says of KJ Boone, but his experience made an oil tycoon feel within reach. “When I’m in his head, I want him to be fond of his life and proud of himself, as I’m sure a person like that would be,” Saunders says. “The trick was to gesture over his head to the reader and say, ‘Did you hear what he just said?’ ”

Vigil takes place over the course of a single night, as Boone is visited by other ghosts in addition to Blaine, but Saunders says he didn’t realise the similarities to Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol until he got halfway through the manuscript.

“I love that book so much. I think everything I’ve ever written has come out from under that umbrella.” He was also inspired, however subconsciously, by Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” and The Death of Ivan Ilyich, as well as Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” and Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.”

“If you’re writing something from a genuine place, you have to notice that there are other stories in the room,” Saunders says, much like the ghosts in KJ Boone’s mansion. “And then you say to your little book, ‘You can’t do any of those things. You have to thread the needle and find a new space.’ ”

Other than Blaine, the most memorable ghost who visits Boone on his deathbed is an unnamed 19th-century Frenchman who built the first internal-combustion engine (likely inspired by Étienne Lenoir, a real-life Belgian-French engineer).

In the afterlife, the Frenchman has grown disgusted with his invention: “It poisons, madam,” he tells Blaine. “I did not know it then.” Instead of comforting Boone during his final hours, the Frenchman tells Blaine, “I advise you to lead him, as quickly as possible, to contrition, shame, and self-loathing.”

But KJ Boone is a hard nut to crack. In a desperate attempt, the Frenchman brings the ghost of Mr Bhuti, an Indian lawyer who died alongside his family when their village was decimated by a climate-change-induced drought. “In the last half hour, we seemed, all at once, to shrivel, become skeletal, look identically ghoulish,” Mr Bhuti tells Boone. “One by one, we succumbed. First Mother. Then Charvi. Then me. That is to say, I had to watch as they succumbed.”

Yet when Jill Blaine enters KJ Boone’s mind, the oil man is unmoved. “He knew about it, about all of it,” Blaine discovers. “[He] just had a bit of a quarrel with the damn logic. There’d always been droughts, yes? Were heat waves a new thing in the world?”

In the early drafts of Vigil, Saunders was “100 per cent for” Jill Blaine’s compassion-driven mission to comfort KJ Boone, despite the CEO’s lack of remorse. She was “the unchallenged hero” of the story. “But I kept listening to the book, and it kept going, ‘Really? Are you sure about that?’ ” Saunders says. Eventually, he decided to end the novel on a note of ambiguity.

In 2013, Saunders’s convocation address at Syracuse University—where he’s been a writing professor for three decades—went viral after a transcript was published on the New York Times website. “What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness,” he said in his speech, before delivering a powerful call for compassion informed by his experience as a student of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.

But today, many Trump-aligned conservatives view compassion and empathy as toxic weapons of the Left, or, as Elon Musk once put it, “the great weakness of Western Civilisation.”

I ask Saunders, Why practise empathy and compassion with people like KJ Boone—or Trump, or Musk, or their legions of admirers—who can’t or won’t practise it themselves?

“A lot of people think compassion means folding up your tent, sitting very serenely somewhere, and letting everything happen,” Saunders says. “But that’s absolutely not true. I don’t see that in the Buddhist tradition. There are some real ass-kickers. Empathy leaves the practitioner in a more powerful position, no matter what, even if you’re on fire with the desire to resist something. Knowing the other team inside out gives you infinitely more power, as opposed to imagining them as cartoon villains.”

When he was very young, Saunders believed that books could save the world. Now he concentrates on the effect books can have on individuals. “I just read [Nabokov’s memoir] Speak, Memory for the first time, and as I was reading I watched myself and realised I was delighted,” he says.

“I got a burst of fondness for everything. That much I believe in, because it’s empirically observable.” But what about the collective crises we face today, like climate change and income inequality?

“I have a feeling that if you were God, and you could look at the world right now—even America, in as sorry a shape as it’s in—you would see readers forming a wall.”

If we’re all “inevitable occurrences” trapped in minds and bodies we never asked for, great books are small deaths that can set you free. Reading one might just be the best way to prepare for checkout time.

Originally published on Esquire US

To mind, there are two car brands that are synonymous with horses and we are only mentioning one of them for the purpose of this post: Porsche. The German brand's logo features the seal of the city that the company is headquartered at—Stuttgart, Germany; taking central position, a rearing black stallion that conveys the power of Porsche's cars.

As this year is the Chinese Year of the Horse, it makes marketing sense for Porsche to do something horse-related. Porsche roped in Singaporean artist Priscilla Tey to work on a mural for the Jewel retail space at Jewel Changi Airport. Titled, "Spirit of Legends", the artwork has horses surge across the wall, their forms dissolving and reforming in mid-gallop.

“I wanted the mural to feel joyful, a little magical, and unique,” Tey says, “and I hope viewers can discover new details in each time they look.” Visitors can also look forward to the Porsche 956 that is displayed on loan from the Porsche Museum. Sitting in the Culture Garage next to the mural, the 956 is widely regarded as one of the most successful racing prototypes in motorsport history. Having achieved four consecutive overall victories at Le Mans from 1982 to 1985, the 956 set a Nürburgring Nordschleife lap record that went unbroken for 35 years. Its racing livery fits in against the mural’s palette of blue, white, red and gold.

As part of the collaboration, there are a range of merch inspired by "Spirit of Legends". This includes T-shirts, thermal flasks and keychains, alongside limited-edition red packets designed by Tey. These are available exclusively at Porsche at Jewel.

"Spirit of Legends" is on public display until 31 March 2025